“A——-, a mantle-maker in a large establishment. Wages 9s. per week, latterly only 7s. 6d., work being slack. Pays 3s. 6d. for room, 1s. for coal, lamp-oil, and firewood, 9d. for washing, which leaves just 3s. 9d. for food and clothing. Lives mostly on bread and tea; carries bread and butter for her dinner to her place of business, as it takes her three hours to walk there and back.”

“As a child of 5, Mabel was sold to an organ grinder in Plymouth and walked many of the roads in Cornwall, singing to raise money for her owner”.

“An interesting little ceremony took place in the grounds of Peamore, near Exeter, on Tuesday when …. Mr Kekewich planted a golden cypress tree. It will be recalled that on the occasion of the visit of the King of Sweden to Exeter several years ago his Majesty stayed at Peamore ….. and planted a tree to commemorate the occasion”.

These are just three of many such anecdotes which are all connected through one man – Father John Hewett, the first Vicar of Babbacombe.

I shall return to the anecdotes later but first I am indebted to the present vicar, Revd Fr Paul Jones, who kindly sent us a pamphlet describing the life of Father John Hewett which was produced on the 100th anniversary of his death with financial support from the Anglo-Catholic History Society. I am reproducing that verbatim here because it accurately conveys the feeling towards Father Hewett for his contribution to founding the church in Babbacombe (and also why should I re-invent the wheel?!!)

THE REVEREND JOHN HEWETT, M.A.

(1830 – 1911)

![]() The first Vicar of Babbacombe (1867 – 1910)

The first Vicar of Babbacombe (1867 – 1910)

LECTOR, si monumentum requiris circumspice (“Reader, if you seek his monument look around you”). Sir Christopher Wren’s son provided a fitting epitaph when the great architect was laid to rest in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral. The same sentiment was recalled 188 years later to acknowledge the life of the Reverend John Hewett. Not that Babbacombe’s first Vicar would have entertained such a vanity for a moment.

Thomas Butterfield, that giant of Victorian church architecture, was responsible for the steepled landmark that has dominated Cary Park for close on 150 years, but it was Father Hewett who established All Saints Church on a firm foundation during his 44 years as Vicar. And although Wren’s epitaph was invoked at the time of his death, Father Hewett had already settled on something more modest for his own resting place. The words he chose have echoed the hopes of countless Christians: In te domine speravi (“In You, O Lord, have I hoped”).

The congregation who mourned his passing in 1911 were in no doubt about their debt to his ministry. An inscription on the rear pillar in the north-west corner of the nave declares: ‘In blessed memory of John Hewett, to whom, under God, is due the building of this church’. And the memorial cross of Portland stone, erected outside the south door, honours a faithful priest and ‘all the good that he has done for his people’.

He had served Babbacombe until his 80th year and if his memory has been somewhat air-brushed from the pages of local history it is fitting that we should cherish his achievements in this, the centenary year of his death.

He was a remarkable figure in so many ways:

- For 20 years, he was the spiritual confidant to the matriarch of one of Britain’s noblest families.

- For one awesome month in 1886, the future Queen Alexandra and her daughters were regular worshippers here.

- His eldest son governed a vast province of India (the Taj Mahal was part of his remit) and was knighted for his services to the British Raj.

- His second son was a rear-admiral who also found fame in India

John Hewett was born at Ewhurst in Sussex on August 6, 1830. He showed early promise as a scholar and on May 12, 1849 – aged 18 – he was admitted to Clare College, Cambridge, graduating with a BA degree in 1853. He had met a young Irish girl, Anna Louisa Lyster Hammon, daughter of a captain in the Honourable East India Company Navy, and they were married in October that year. Their first child, John Prescott Hewett, was born at Barham, near Canterbury, in 1854. By now, Father Hewett had committed himself to a life in holy orders and he was ordained deacon at Chichester Cathedral in 1855.

For his first appointment, he served as curate at the 1066 village of Battle in Sussex, and a second son, George Hayley Hewett, was born there in November.

Father Hewett had continued his studies at Clare College and in 1856 he graduated as an MA. It was also that year that marked his ordination to the priesthood at Peterborough Cathedral. In 1857 he moved to Compton Martin in Somerset, where his eight years as rector were marked by the births of two daughters and another son.

Torquay, meanwhile, was entering a long period of urban development and a sharp rise in population. In 1860 Prebendary Reginald Barnes had become Vicar of St Marychurch and he superintended the opening and consecration of the rebuilt parish church in July 1861. When Father Hewett and his family moved to Devon in 1865 his appointment as curate augured well for a flourishing parish.

When he arrived, the population of ‘Babbicombe’ was no more than 600. It was regarded as a cliff top hamlet situated some distance from the mother church. At the end of his first nine months the young curate realised there was a great need for a new church. By now the population had grown to 850 (and likely to double before building work was completed).

When a public meeting was held in the Schoolroom in November 1865 local feeling was strong – Babbacombe needed its own parish church. Father Hewett was quite ‘startled’ at the rapid increase in population and expressed his concern that the Church of England should erect a new building before any new chapels filled the void.

The foundation stone was laid on December 20, 1865, and building work got under way. Two further sons were born in those early years and Father Hewett was appointed Vicar in 1867, prior to the consecration of the building on All Saints Day (November 1) by the great Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford.

The innovative William Butterfield (1814-1900) was one of the most distinguished architects of the Victorian era and his design incorporated 50 varieties of Devon marbles. The pulpit and font, with their intricate polychromatic marbles, remain outstanding examples of his art to this day. When Gerard Manley Hopkins, the Jesuit poet, visited the church a few weeks before its consecration he described Butterfield’s work as ‘pure beauty of line’.

Work on the chancel began in September 1872 and the completed church, with its tower and spire, was opened on November 1 1874. The inhabitants of the new parish were generally poor. In fact, a quarter of Torquay’s population were in domestic service. Babbacombe had no schools to speak of and religious observance was held in light esteem. Father Hewett’s untiring zeal put All Saints Church at the hub of the community. He was an exemplary social worker, sympathetic and earnest, an ardent supporter of the temperance cause and famed for the ‘rare eloquence’ of his sermons.

He was to serve as Rural Dean of Ipplepen from 1879 to 1892. By now the most distinguished member of his regular congregation was the Duchess of Sutherland (former Mistress of the Robes to Queen Victoria). Her husband was one of the richest landowners in the country and a close friend of the Prince of Wales. But the most exalted figure who ever visited the church was the much-beloved Princess of Wales (the future Queen-Empress consort of Edward VII). Alexandra and her three daughters stayed with the Duchess in her villa in the Warberries for a five-week visit that elated Torquay throughout March 1886. The noble ladies shared a devout faith and their presence at All Saints Church every Sunday ensured overflowing congregations.

Father Hewett suffered a personal loss in 1884 with the death of his wife at the age of 55. Two years later he married Miss Anne Robson, of Sunderland, and he was able to take pride in his growing family, particularly the two eldest sons. John Prescott Hewett had entered the Indian Civil Service in 1877 and became Lieutenant-Governor of the Provinces of Agra and Oudh. He organised George V’s Coronation Durbar in Delhi in 1911 and was honoured with several knighthoods. George Hayley Hewett, the second son, served in the Zulu War, achieved the rank of rear-admiral and became director of the Indian Royal Maine. Both brothers were included in Who’ Who.

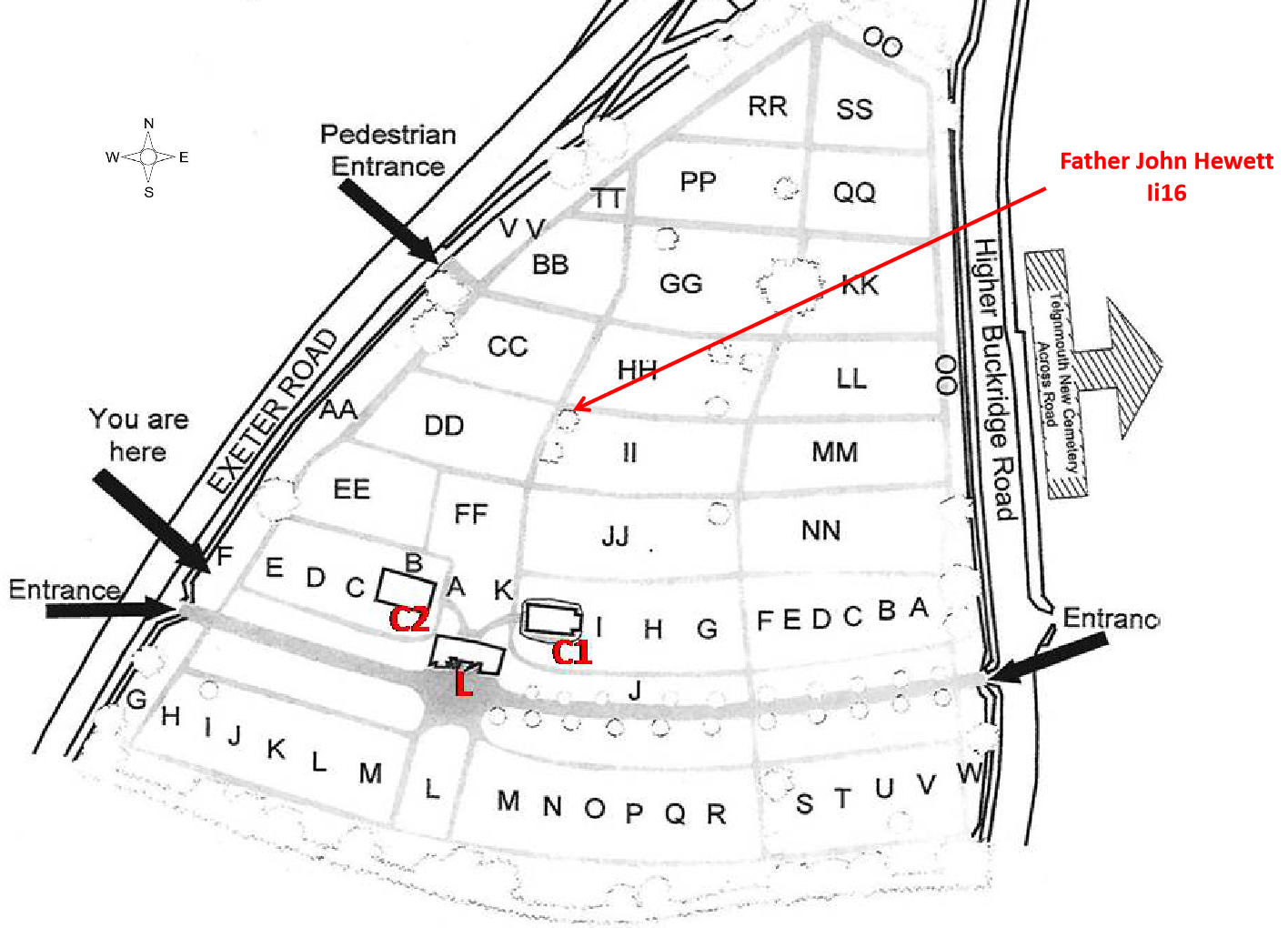

As the years began to take their toll, Father Hewett resigned as Vicar in his 80th year in August 1910. He retired to Teignmouth and died in his seafront home on August 5, 1911. He was buried at Teignmouth Cemetery: his wife’s grave was laid alongside 12 years later. A stained glass window was dedicated to his memory in the north aisle of the church in January 1913, followed by the erection of the memorial cross in May.

But it is the sentiment of a contemporary obituary that has resonated most clearly over the intervening centenary since his passing: ‘His outward memorial stands today in the glorious church of All Saints, the building of which, stone by stone and stage by stage, he was allowed to watch and superintend. The souls of men, women and children, built by him, under God, strong in faith, into a spiritual temple, will stand in the last great day as an imperishable testimony to his work and worth.’

Written by Ian Woodford, a regular worshipper at All Saints, Babbacombe.

Fr Hewett’s grave alongside that of his second wife, Anne, in Teignmouth Old Cemetery

Interior view of All Saints Parish Church, Babbacombe by Roger Perdue

Memorial window to Fr John Hewett in All Saints Church, Babbacombe reproduced by courtesy of Pyramid Photography, Torquay

All Saints’ Church, Babbacombe and the Memorial Cross for Fr John Hewett

The Anecdotes

The pamphlet refers to Father John Hewett as “an exemplary social worker” and it is that aspect of his character which probably best underpins the first two anecdotes.

The Mantle-Maker’s Tale

“A——-, a mantle-maker in a large establishment. Wages 9s. per week, latterly only 7s. 6d., work being slack. Pays 3s. 6d. for room, 1s. for coal, lamp-oil, and firewood, 9d. for washing, which leaves just 3s. 9d. for food and clothing. Lives mostly on bread and tea; carries bread and butter for her dinner to her place of business, as it takes her three hours to walk there and back.”

The above extract comes from the book ‘Concerning men, and other papers’ by a female Victorian writer Dinah Craik. It forms part of the chapter entitled ‘The House of Rest’ which describes her visit to this House and what she learned about how the House worked and the background of some of the women staying there. The House is what we might describe today as a short-term respite centre for women.

Another example she gave:

“ ‘We all of us have something more or less wrong with our lungs’ said one girl. And no wonder. In … one of the largest establishments in London the workroom is only lighted by a skylight, bitterly cold in winter, baking hot in summer. Sixty women work in it, and it is warmed by one small stove.”

The House of Rest was in Babbacombe. It was conceived and run on a daily basis by two sisters – the “Misses Skinner” – who sound like a determined, and perhaps formidable, duo. It had patronage of the Duchess of Sutherland and Father John Hewett was actively involved in its inception and ongoing governance. As you can gather from the two extracts above it was intended to provide rest and recuperation for working women who suffered or were under pressure in their working conditions.

The House operated, I would say, under Christian values but was most definitely non-proselytising (the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette of 29 December 1883 confirmed this: “Visitors are received irrespective of religious distinctions”). It was also careful not to portray itself as complete charity – whilst it was heavily subsidised through donations it also insisted that those visiting also had to make some financial contribution. It’s aethos actually seems very akin to St Benedict’s “Rule” of compassion and discipline (which appeared in the story of Countess English).

Starting up in 1878 it went from strength to strength, ending up as three houses able to accommodate upto 30 women at a time. I would say that its growth stemmed from the determination and commitment of those running it. It promoted itself extensively throughout the country. Here is an example from the Reading Mercury of 28 February 1880:

“HOUSE OF REST FOR WOMEN IN BUSINESS.

To the EDITOR of the READING MERCURY.

SIR, – A House of Rest to afford change and recreation to young women in business where they can obtain a timely rest to prevent serious illness, and where they can obtain a timely rest to prevent serious illness, and where they can spend their annual holiday, has been opened at Babbacombe, in Devonshire. It is open all the year round.

I should be grateful to you if you would kindly allow me to make it known to those whom it is intended to benefit through the medium of your Paper, which I am aware is widely circulated.

The weekly payment is 5s., when introduced by a Subscriber, for a period of three weeks. The House is under a Committee of Management, consisting of the Rev. John Hewett, M.A., the Duchess of Sutherland, Miss Roberts, and the Misses Skinner. All information will be given to any young women in business respecting it, or to any others interested in it, on application to Miss Skinner, Bayfield, Babbacombe.

The need of some House of Rest for women engaged in shops, millinery, dressmaking, etc., has been long felt by them, and it is believed that this effort to supply the need and afford the comforts of a temporary resting place now offered to weary women in business will be appreciated by them. Numbers have already made use of it, and have derived much benefit from their visits, many indeed having been completely restored to health by its means.

Yours faithfully, C. E. Skinner”

I don’t want to go into the detailed history of the House of Rest but I thought it was worth quoting a contemporary description of its establishment which I have added in an addendum at the end of this blog. Craik’s book is also well worth reading as is a good blog post ‘Fernybank House of Rest for Women in Business” which presents a well-researched history.

To conclude this anecdote though I want to return to Craik’s book. The House of Rest could never be a solution to working conditions that women were subject to in late Victorian Britain. It could only offer some temporary respite and hope that that would somewhat alleviate the stress that working women were under. Craik says of the House of Rest:

“It does not profess to cure the sick, or reclaim the wicked; it goes on the principle that ‘prevention is better than cure’, and that to guide people into the right way is safer and more efficacious than to snatch them out of the wrong one ….”

And gives the realistic assessment that those working conditions still claimed lives:

“Of the thousand women who in ten years have visited the House of Rest, and whose after career has been, as usual, silently watched by their friends there, many, only too many, have died; but only one has, to use the customary and most pathetic word, ‘fallen’”.

Mabel’s Tale

“As a child of 5, Mabel was sold to an organ grinder in Plymouth and walked many of the roads in Cornwall, singing to raise money for her owner”

This is a snippet from the autobiographical book A Cornish Waif’s Story by Emma Smith (pseudonym, real name Mabel Carvolth) published in 1954 when the author was in her sixties. Briefly, Emma was the illegitimate child of a ‘slipshod’ woman and abandoned, to be put in the Union (the workhouse in Redruth) and then left with the Pratts ( the organ grinder) in a Plymouth slum where she shared a filthy, infested room with them and others. She was turned out onto the street at age 9 and eventually ended up at the Devon House of Mercy in Bovey Tracey. She finds some peace there and stays until age 15 when she returns to the world, enters service and eventually marries.

It is the Devon House of Mercy which is the context of the next link with Father John Hewett.

There are a lot of source references to the House of Mercy. Kelly’s Directory of 1902 refers to it thus:

“The Devon House of Mercy for the Exception of Fallen Women, in this parish, was established in 1861, and formally opened in 1863, the foundation stone of the permanent house having been laid by the late Earl of Devon in 1865: 90 inmates are received from all parts of the country, and instructed with the view to their establishment in some respectable calling : the institution is supported by voluntary contributions, and is under the care of members of the Clewer (Windsor) Sisterhood ; in connection with this house is the St. Gabriel’s Mission for work among the poor, carried on by the same Sisterhood.”

There is a particularly good summary by Frances Billinge on the Bovey Tracey History site which gives a number of examples of the intake at the House of Mercy:

“Mary Ann Barwick was born in Wootton Courtney in Somerset in 1856. From the 1861 census we learn that her father George was an agricultural labourer and the family lived at Ford. On 11 March 1870 Mary’s son Edmund was baptised at the local parish church and no father was named. This led to Mary’s placement in Bovey Tracey.”

And the book Prostitution and Victorian Society gives a shocking statistic:

“Between 1863 and 1870 90 percent of the women sent to the Devon House of Mercy from the lock wards of the Royal Albert were half or full orphans.”

The Royal Albert was the hospital in Devonport and the “lock wards” were where women with venereal disease were kept. The Old Devonport web-site reveals:

“In addition to the requirements of a normal hospital, it would also contain a Female Lock Ward of at least twenty-five beds, this being at the express request of the Government under the Contagious Diseases Act”

The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette of 11 December 1883 also made an interesting comment:

“During the thirteen years preceding 1881, 476 women were received into the House: of these 131 had been received only from the Royal Albert Hospital – an excellent institution at Plymouth.”

The presence of the ‘Lock ward’ was symptomatic of the social problems caused not just by a naval presence but also poverty. This had been recognised 20 years earlier too when the House of Mercy was first proposed as reported by the Western Daily Mercury of 6 September 1864:

“According to a report recently made in Parliament there are on the streets of Plymouth, Devonport, and Stonehouse, earning the bread of infamy, no less than 900 children under the age of fifteen. The total number of this class of all ages within the county is probably upwards of 5,000.”

All of the above points to the huge social need there was to support girls and women who were unable to provide for themselves, for numerous reasons, through the socially acceptable norms of the time. The House of Mercy was a solution. With the benefit of hindsight, looking back at Victorian society, you wonder whether institutions like this were born from compassion or, maybe, societal guilt – probably some combination of the two.

Anyway, in 1882 Father John Hewett became involved. As the Western Times of 25 January reported:

“Your Committee have to report with deep regret the loss by death of two members of the Council, the Earl of St. German and the Rev. Dr Harris. They recommend Charles A. W. Troyte, Esq., of Huntsham Court, and Rev. John Hewett, Rector of Babbacombe to fill the vacancies.”

Father Hewett was soon encouraging people to support the work of the House of Mercy as the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette of 11 December 1883 noted when reporting on a meeting at the Temperance Hall of Paignton, presided over by the Earl of Devon, in aid of the Devon House of Mercy:

“The Rev. J. Hewett moved that ‘this institution deserves the cordial support of all persons, as materially conducive to promote morality and virtue, and to facilitate a return to an honest and virtuous life of those who had fallen into sin’. The work of the House of Mercy was, the rev. Gentleman said, truly one of Christian charity, and one which everyone should support and encourage as a Christian duty. If they could even survey the domestic working of this admirable institution he was sure that everybody present would support it by their contributions and by their prayers. (Applause.)”

Unfortunately that is the last reference I can find to Father John Hewett and the House of Mercy. All of the official records for the Devon House of Mercy are now held at the Berkshire Record Office which charges not inconsiderable fees for copies or searches of the archives.

It is interesting to note though that two of the major institutions supported by Father Hewett were both associated with the plight of women in society.

The Kekewich Tale

The final anecdote brings us back to Father Hewett’s normal clerical duties but it is illustrative of the day-to-day dealings he had with all levels of society.

“An interesting little ceremony took place in the grounds of Peamore, near Exeter, on Tuesday when …. Mr Kekewich planted a golden cypress tree. It will be recalled that on the occasion of the visit of the King of Sweden to Exeter several years ago his Majesty stayed at Peamore ….. and planted a tree to commemorate the occasion”.

The Domesday Book of 1086 records Peamore as one of the holdings of Ralph de Pomeroy, the first feudal baron of Berry Pomeroy, Devon. It was acquired by Simon Kekewich, the Sheriff of Devon, in the early 1800s.

The above extract is from the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette of 5 October 1934 and refers to the celebration marking the golden wedding anniversary of Mr . and Mrs. Lewis Pendarves Kekewich. And yes they were married in All Saints Church, Babbacombe, on October 2nd 1884 with the bride’s uncle and the Rev. John Hewett officiating, as the Morning Post of 7 October 1884 reported:

“KEKEWICH-HANBURY. – On the 2d ist., at All Saints’, Babbacombe, by the Rev. F. Hayward Joyce, vicar of Harrow, assisted by the Rev. John Hewett, Lewis Pendarvis, third son of Trehawke Kekewich, Esq., of Peamore, to Lilian Emily, eldest daughter of Sampson Hanbury, Esq., of Bishopstowe.”

The Later Years

As we have seen Father Hewett’s wife died in 1884 and two years later he re-married Anne Christian Robson. References to him in the local papers are very much focussed on what we might call the normal clerical duties in a small community – marriages, deaths, community work with parish organisations such as the flower show, the working men’s club whilst he also maintained an active involvement in the Gospel Temperance Movement.

It seems surprising that he kept going in his role until he was 80, retiring in 1910. An interesting comment in the Torquay Times, and South Devon Advertiser of 20 April 1906 indicated that though he might be slowing down a little he still seemed to have all about him:

“Mr. Hewett is now getting into years with the indications of age showing themselves apace, though there is no diminution of intellectual clearness and vigour. His countenance is benignant and pleasant, and his voice is clear and ringing, in spite of his years, capable of any modulation or variation in its tones and accentuations. He is, or might be, an orator -”as Brutus is.” While his action is graceful and his attitudes classical, he is in his preaching earnest and impressive. His sermons are stated to be above the average in interest and acceptability, although he does not always burden the minds of his hearers with the ponderous stores of his own learning.”

In 1910 they retired to Teignmouth, living at the time of the 1911 census at 1 Carlton Place. He died only a year later on 5th August 1911 and was buried in Teignmouth Cemetery. His wife was placed in the grave next to his on her own death some 12 years later. They are in plots Ii16 and Ii17.

As part of the centenary of his death in 2011 flowers were laid on his grave.

Some Loose Ends

House of Rest. For a contemporary account of the House of Rest for Overworked Women see the addendum after the References section. Emily Skinner died in 1922. The house itself still exists, converted to holiday apartments.

The Devon House of Mercy. The sisterhood continued in Bovey Tracey until 1939. The building has been converted into flats.

His family background. His father, John Short Hewett, also went to Clare College, Cambridge and entered the clergy. The biographical write-up of Cambridge Alumni suggests though that their economic circumstances were somewhat different. John Short Hewett entered Cambridge as a ‘sizar’ which means that he received an allowance toward college expenses often in return for doing a defined job such as acting as a servant to other students. This could be explained by a reference to John Short Hewett’s father being “a country gentleman whose fortune was said to have suffered from his love of horse racing”.

John Hewett was more fortunate in entering as a ‘pensioner’ meaning that he didn’t require financial assistance. However, he must have had a turbulent childhood since his father died in 1835 when he was only five years old and his younger brother, Thomas Hardwicke aged seven, six years later. Curiously they both died in Boulogne. Also curiously his mother re-married a Thomas Hardwicke in 1840 who also seems to have been a rector and died 15 years later.

His mother and sister (Felicia) then seem to have moved in with her brother in Bishopsteignton but she may have subsequently moved on to Ireland and Darmstadt, Germany. If so she appears to have returned to the UK shortly before her death in 1873 and was staying with her son at St Alban’s House, Babbacombe.

His uncle. The Torquay Post and South Devon Advertiser of 26 June 1891 announced (getting the relationship wrong!):

“The Rev. John Hewett, vicar of Babbacombe, has sustained a bereavement in the death of his brother, Sir Prescott Gardener Hewett, F.R.S., who died on Friday night, at his residence, Chestnut Lodge, Horsham, Sussex, from congestion of the lungs, following on an attack of influenza.”

As well as being president of the College of Surgeons he was also surgeon extraordinary to Queen Victoria. His obituary in the St. George’s Hospital Gazette includes the epitaph:

“Few men have ever left the world with a more stainless record of duty honestly done and of success won by no ignoble means.”

It could be said that this equally applied to his nephew, Father John Hewett.

The Duchess of Sutherland. Father John Hewett would have know the Duchess of Sutherland well since she was the patron for the House of Rest and also a regular attendee at All Saint’s Church.

She died on 25th November 1888 (aged only 59) and, as the Torquay Times , and South Devon Advertiser of 30 November 1888 reported:

“It was not, we believe, until Saturday that her Grace’s illness took a serious turn, and even then her medical attendants were not apprehensive of immediate danger, though at her request the Rev. J. Hewett, vicar of All Saints, Babbacombe, where her Grace regularly attended, was telegraphed for and he proceeded at once to London, and on Monday came the melancholy intelligence of her demise.

….. she was a daily attendant at All Saints’, Babbacombe, where she was always working in the parish.

….. The Rev. J. Hewett, vicar of All Saints’, Babbacombe, and the Rev. W. E. Hampshire were present at the railway station (to receive the coffin) and received those mourners who travelled by the same train.

….. The service which was brief, solemn, and impressive was conducted by the Rev. J. Hewett

….. The first part of the burial service was read by the Rev. Canon Body, and the second portion by the Rev. J. Hewett.”

She is buried in Torquay cemetery and commemorated at All Saints Church as The Queen of 29 November 1890 describes:

“At All Saints’ Church, Babbacombe, a handsome stained-glass window, which has been place in the church in memory of the late Duchess of Sutherland, was last Saturday dedicated, the service being conducted by the vicar, the Rev. John Hewett. Among the congregation were Lady Mount-Temple, Lady Symonds, and the Lady Macgregor. The Princess of Wales, who stayed with the Duchess when she visited Torquay a few years since, is one of the subscribers to the window, the subject of which is ‘The Holy Women at the Tomb’”.

Sources and References

Extracts from contemporary newspapers are referenced directly in the text and are derived from British Newspaper Archives.

Ancestry.com for genealogy

Wikipedia for general background information

Other sources, with hyperlinks as appropriate, are as follows.

Father John Hewett

Pamphlet reproduced in article

Anglo-Catholic History Society – funding of pamphlet

Memorial Cross photograph – Copyright John C and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

All Saint’s Church

All Saints Babbacombe – website

All Saints Babbacombe – blog

Kelly’s Directory of Devon 1902 – general description

Pictorial & Historical Survey of Babbacombe & St Marychurch Volume 2 (A-J) compiled by Leslie Lownds Pateman – index

House of Rest

Fernybank House of Rest for Women in Business – JS Blogspot –

Concerning men, and other papers. By the author of John Halifax, gentleman. By Craik, Dianh Maria Mulock, 1826-1887 –

Devon House of Mercy

Bovey Tracey History Society –

Project Canterbury – Harriet Monsell: A Memoir, Rev. T. T. Carter, E.P.Dutton 1884 –

Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women, Class, and the State by Judith R Walkowitz –

A Cornish Waif’s Story, Emma Smith, 1954 – with online extract and reviews

And review …

And review …

Sir Prescott Gardner Hewett:

Distinguished St George’s Men’, St George’s Hospital and Medical School Gazette, Vol III, Issue 25 –

Addendum

For those interested here is a fuller contemporary account of the House of Rest from the Morning Post of 19 August 1878:

“HOUSE OF REST FOR OVERWORKED WOMEN.

A week ago the House of Rest, a description of which we extract from the current number of Social Notes, was opened, and the first six inmates were received within its hospitable walls. This charity is in great want of funds, and we recommend it to the attention of those who approve of this deserving scheme:

‘The condition of a large class of young women employed in shops, millinery, dressmaking, &c., in our large town has of late attracted much attention. In London alone there are , it is reckoned, about 20,000 in shops, exclusive of those engaged in private millinery and dress-making establishments. Early and late they toil for a bare livelihood, pinching and saving to make both ends meet. The narrow means of a great proportion compel them to sleep in close, ill-ventilated rooms in miserable lodgings, and to content themselves with scanty fare. Their hours of work are long; lasting in many cases from eight o’clock in the morning to nine o’clock at night, and in London, during the season, too often they are obliged to work all night. The necessity of being always at their post, at the peril of losing their situations, will not allow them to attend to the trifling ailments that are the precursors of more serious sickness.

Under these circumstances is it any wonder if, with lowered health and overstrained nerves, they fall victims to the first severe illness that attacks them, drop out of the ranks of their fellows, and their places know them no more? Now do we not desire to make morbid and sentimental complaints on the part of female workers. If women work for their bread they must suffer in working; it is the condition of work as society is at present constituted, and women, like men, must accept that condition. We only desire to help this class, so hard working, and in the main so respectable, to endure the condition without sinking under it.

Remembering always that ‘prevention is better than cure’, we desire to arrest the overworked, overstrained state both of body and mind which is so surely the harbinger, sooner or later, of serious disease. Let us consider what we of the higher classes do when lowered health and overtaxed nerves carry us to the verge of illness. If we are wise, we take the matter in time, go away for a rest, for a change of air and scene, and consider money well laid out in bringing us a return of health.

If we shrink from illness and strive to avert it – though it does not mean for us, as, alas! It does for them, want of bread and debt – with what terror must those who have nothing to turn to to look at it when it overtakes them. We will not inquire what becomes of them in such cases, we will rather ask what we can do to prevent their reaching that heart-rending point. Let us step in to their aid before illness supervenes, and try to stop its approaches.

A timely rest will often avert it. Prevention is not only better, but more economical than cure. It may be urged that all aid to the working classes to be of permanent benefit to them, should consist in helping them to help themselves; and, indeed, the scheme that has lately been started for enabling these tired workers to take a brief season of rest (of which I desire to lay a short sketch before your readers) includes some payment on their part, and some provident care to lay by money for that payment; but, when the element of self-help is thus recognised, surely it is permissible to supplement that self-help – to give some aid towards such needful rest.

Some little assistance may be offered by those who have means for rest and change to those who have no means for either, without pauperising them. Only a short rest, just enough to set them on their feet and enable them to work again for themselves. Those who study the proportion of their wages to the necessity of their living will see they cannot procure the boon without some such aid; their earnings only enable them to pay their way with the strictest economy, without allowing any margin for the expenses of a holiday; and yet it is just such a holiday that would save many a toiling worker from breaking down altogether.

What is wanted to meet the cases of which I am now speaking, at this particular point, is not an hospital – they are not ill enough to be admitted within its walls; not a convalescent home – they are not recovering from illness to justify their admission; but a house of rest to prevent sickness. It has been a ‘missing link’ hitherto in our varied benevolent efforts, with, indeed, one or two admirable exceptions – the House of Rest for City Missionaries, so generously advocated by the Rev. P. B. Power, and a house of rest on a different basis, formed by the clergy for their own use on temporary cessations of their labour. Surely a House of Rest for overworked women, especially of the class of whom I have spoken – shopwomen, milliners, and dressmakers’ assistants in all large towns, and, indeed, any others who require such aid – will prove of the same benefit to them that we know the House of Rest for City Missionaries has been to hard-working men.

In pursuance of this idea a small house has been taken in a high, healthy situation close to breezy downs in the centre of beautiful scenery at Babbicombe in Devonshire. The rent has been given by a lady, and the house furnished by donations kindly supplied for that purpose by many others interested in the work. The size of the house will enable 60 women to avail themselves of the benefits of it during the course of one year. The climate – bracing in summer and yet soft in winter – will make the little home a pleasant resting place at both seasons. If the undertaking prove successful we hope to enlarge our borders and take in greater numbers.

The rent and furniture being already given, for the yearly maintenance of the house we appeal to all who feel that this scheme supplies a want, and who are willing to aid by donations and especially by annual subscriptions, in carrying it out. The promoters of the plan have thought it best, and their opinion has been confirmed by many other experienced workers, to make the house, as far as possible, self-supporting. It is proposed, therefore, to give to each annual subscriber of £1 1s. a yearly ticket of admission for a period of three weeks, and to ask in addition from each person availing herself of such ticket a weekly payment of 5s. This sum, it is hoped,she may be able to lay by during the year in prospect of rest and relief, for at least a short time, from harassing cares about ways and means.

The House of Rest will be under a committee of management consisting of the Rev. John Hewett, vicar of Babbacombe and rural dean; the Duchess of Sutherland, Stafford House, London; Miss Roberts, Florence Villa, Torquay; the Misses Skinner, Bayfield, Babbacombe, who will thankfully receive subscriptions and donations towards the support of the work.

The promoters of the scheme desire especially the co-operation of the heads of houses of business in London and the large towns to assist them to carry it out, both in affording opportunities for short periods of rest at such seasons as may be convenient to themselves, and in giving annual subscriptions for tickets, which they may distribute to such of their employess as they choose to select. Some of the leading houses have already subscribed, and it is hoped that others will follow their example.

Those who themselves enjoy the varied charms of this lovely spot would like to share its beauties with dwellers in towns. When we look out of our windows in the early morning and see the soft green of the trees, the silvery tints of the sea, and the purple distances of the moors – hear the call of the cuckoo, the whistle of the blackbird, and the song of the thrush – we cannot but long for some of the wearied workers in our great cities to see and hear them too. I am sure they would go back to their work strengthened by even a short contact with these glorious gifts of God.

And so I plead not only for the physical good, great as I believe that would be, but for the mental and even spiritual refreshment which a brief sojourn in this loveliest part of our lovely Devonshire would be to worn-out toilers in our large towns. I think, though they may not recognise it, they have a longing for beauty as well as for rest. A little glimpse of it would enable them to set to work again with fresh courage as well as renewed strength. It is so hard for them to watch London emptying into the country, and they without a chance of seeing a green tree or a wild flower, every one, as they think, getting a holiday but themselves. And – no slight benefit – it would soften the bitterness with which they must sometimes look on the pleasures of those more happily situated than they are, if they could feel that the desire to give them enjoyment entered into the hearts and lives that now seem separated from theirs by an impassable gulf. And I think it would sweeten the holiday of many a bright girl in the higher ranks to feel that she had helped a working sister to a taste of the pleasures so freely lavished by loving care on herself; and would even heighten the satisfaction of heads of households in the summer recreation which they plan for their own families to feel they have been the means of extending such rest and enjoyment to those whose failing health has no parent’s eye to detect and no watchful care to avert.

In conclusion, I may add that we shall be grateful to all who will make this work known both to those it is intended to benefit and to those who are willing to assist us in carrying it out. Some, we hope, will give us help in money; all, we trust, will wish us God speed!

C. E. Skinner

Amazing research …fascinating historical info connected to the life and work of Rev Hewett first vicar of All Saints Babbacombe

LikeLike

Interesting! I believe that my g-g-grandfather’s elder sister was married to a carpenter who worked on the building of Babbacombe church. I was given a copy of a photo which I was told was of them outside the new church.

Regards Liz Davidson

On Mon, Aug 31, 2020 at 11:19 PM Teignmouth Old Cemetery wrote:

> Everyman posted: ” “A——-, a mantle-maker in a large establishment. > Wages 9s. per week, latterly only 7s. 6d., work being slack. Pays 3s. 6d. > for room, 1s. for coal, lamp-oil, and firewood, 9d. for washing, which > leaves just 3s. 9d. for food and clothing. &n” >

LikeLike

Hi Liz. Just catching up on old posts here so apologies for the delay in replying. It’s always nice when stories like yours emerge – it’s what makes historical research come to life! Is it possible to see a copy of the photograph? If you could scan it or take a photo of it & email it to me that would be great. All the best, Neil

LikeLike