Had Margaret been born male she probably wouldn’t have been buried in Teignmouth Old Cemetery. She would probably have been interred in the churchyard of the Dartington estate, Totnes. She would probably have had a memorial plaque in the church tower. Parliamentary history would have changed and who knows what else might have changed by now.

But that didn’t happen and Margaret Champernowne was buried in a small tomb-like grave in one of the earliest consecrated sections of Teignmouth Cemetery (plot A30).

The Champernowne name reputedly derived from the parish of Cambernun in the canton of Coutances in Normandy[1]. It arrived in England with the Norman conquests when the family would have been rewarded for their service and fealty with land in the conquered country. This was mostly in Devon and Cornwall. The village of Clyst St.George just outside Exeter was originally known, for example, as Clist-Champernon.[2] In Devon over about the next 600 years, through acquisition and inheritances, branches of the Champernowne family continued in other manorial estates in Ilfracombe, Modbury and North Tawton.

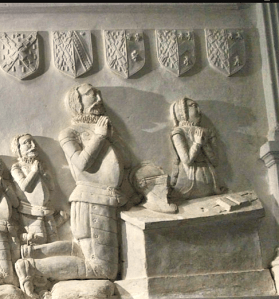

Then in 1559 Sir Arthur Champernowne, Sheriff of Devon and Vice-Admiral of the West under Queen Elizabeth 1, acquired the feudal barony of Dartington, Totnes, previously the home of the 3rd Duke of Exeter.[3] He and his wife are commemorated on a frieze on the wall of the remaining tower of St Mary’s church in the Dartington estate.

A subsequent succession of Champernownes ended with Rawlin and his wife Agnes.

Rawlin, born 1726, was the eldest son of Reverend John Champernowne and his wife Margaret both of whom died when Rawlin was still young. It’s not clear who looked after Rawlin and his siblings when their parents died but Rawlin subsequently entered the navy in 1756. In 1757 he was serving as a Lieutenant under Captain James Cook on HMS Solebay, patrolling the Scottish coast as part of the country’s defence activities in the Seven Years war[4]. He succeeded to the Dartington estate in 1766 on the death of the then incumbent, his cousin Arthur Champernowne. In 1770 he married Agnes Hore Trist; their daughter Margaret was born two years later (note that her date of birth has been incorrectly inscribed as 1782 on her grave!).

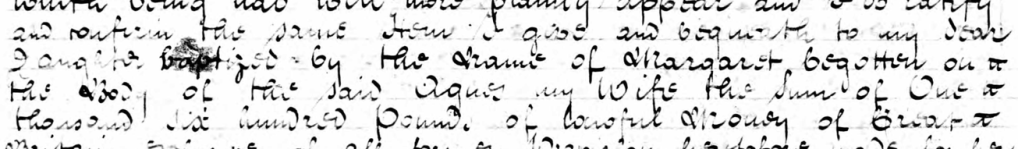

Rawlin died two years after that and Margaret remained their only child. It turns out though that Rawlin had sown some wild oats and had two other illegitimate children. Interestingly he recognised them in his will[5]: a “supposed’ daughter, Elizabeth, by Joan Philips; and a ‘reputed’ son, Humphry, by Grace Barnes”. The will also refers to Margaret as “my dear Daughter baptised by the name of Margaret begotten out of the body of the said Agnes my Wife”.

Rawlin and Agnes are commemorated on a marble slab[6] in the same old church tower as Sir Arthur.

And so we come full circle. Under the arcane rules of male primogeniture this line of the Champernownes officially died out. If only Margaret had been male it would have been simple. Rawlin’s only son Humphry was illegitimate and therefore didn’t qualify for such inheritance; and there were no other male contestants remaining in the reverse natural chain of relations. Somehow an extraordinary convoluted solution was cobbled together and legitimised.

Jane, the daughter of the Arthur Champernowne who died in 1766 and aunt of Rawlin, subsequently married a Reverend Richard Harrington, younger son of Sir John Harrington Bart and rector of Powderham (the Courtenay estate). They in turn had a son Arthur.

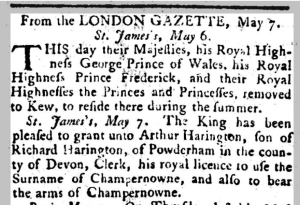

Even though Jane had died before Rawlin and Richard Harrington had also remarried before Rawlin’s death it was deemed that Arthur, barely seven years old, could become heir to the Dartington estate on condition that he changed his surname to Champernowne.[7] This required royal assent which was duly given as announced in the London Gazette[8]:

Arthur became member of parliament for Saltash in a brief parliamentary career which ended ignominiously in 1807 when he was unseated on petition[9]. He died 12 years later aged only 52. You must wonder whether the cobbled-together inheritance marked the start of the decline of the Dartington estate. Arthur apparently in a grand tour of Europe had amassed a vast collection of art, a Who’s Who of the grand masters – Rembrandt, Titian, Caravaggio, Rubens to name but a few[10]. Presumably this was just part of his profligacy because by the time of his death he was in debt to the tune of £25,000. By the end of the 19th century what was left of the estate was derelict ruins – the collection of artwork had been sold (at a considerable loss), as had two-thirds of the land.[11].

Meanwhile Margaret, with what would have been a generous financial inheritance from her father and subsequently her mother (died 1811), had at some point moved to Teignmouth. She never married and is shown in 1841 as a lady of independent means living in Dawlish Road with two servants – Jane Marsh, cook, and Elizabeth Easterling(?), housemaid. It looks as though she remained there until she died aged 88 on 16 October 1860.

To summarise almost 1800 years of Champernowne history there is this quote from the Battle Abbey Roll[12]:

“There have been, writes Prince, many eminent persons of this house, the history of whose ancestors and exploits, for the greater part, is devoured by time, although their names occur in the chronicles of England, amongst those worthies who with their lives and fortunes were ready to serve their King and country”

A portrait of Margaret’s mother Agnes painted by Philip Mercier when she came out, so probably around age 18, could perhaps reflect Margaret’s own likeness at a similar age[13].

Sources and References

Extracts from contemporary newspapers are referenced below and are derived from British Newspaper Archives.

Ancestry.com, Wikitree, Geni for genealogy

Wikipedia for some general background information

Other sources, with hyperlinks as appropriate, are as follows.

[1] Patronymica Britannica from Altogether Archaeology

[2] Magna Britannia from British History

[5] Copy of the will held at Devon Heritage Centre

[6] Photograph from Historic England

[7] Magna Britannia from British History

[8] Police Gazette 29 April 1774

[10] From an article, ‘Sale of the Century’ by a great, great, great, great grandson descendant of Athur, Barney Spender, which gives a much more detailed account of the artwork involved

[11] Notes from Dartington Parish Council

[12] Battle Abbey Roll with some account of the Norman Lineages by the Duchess of Cleveland 1889.

[13] Country Life 1 January 1959