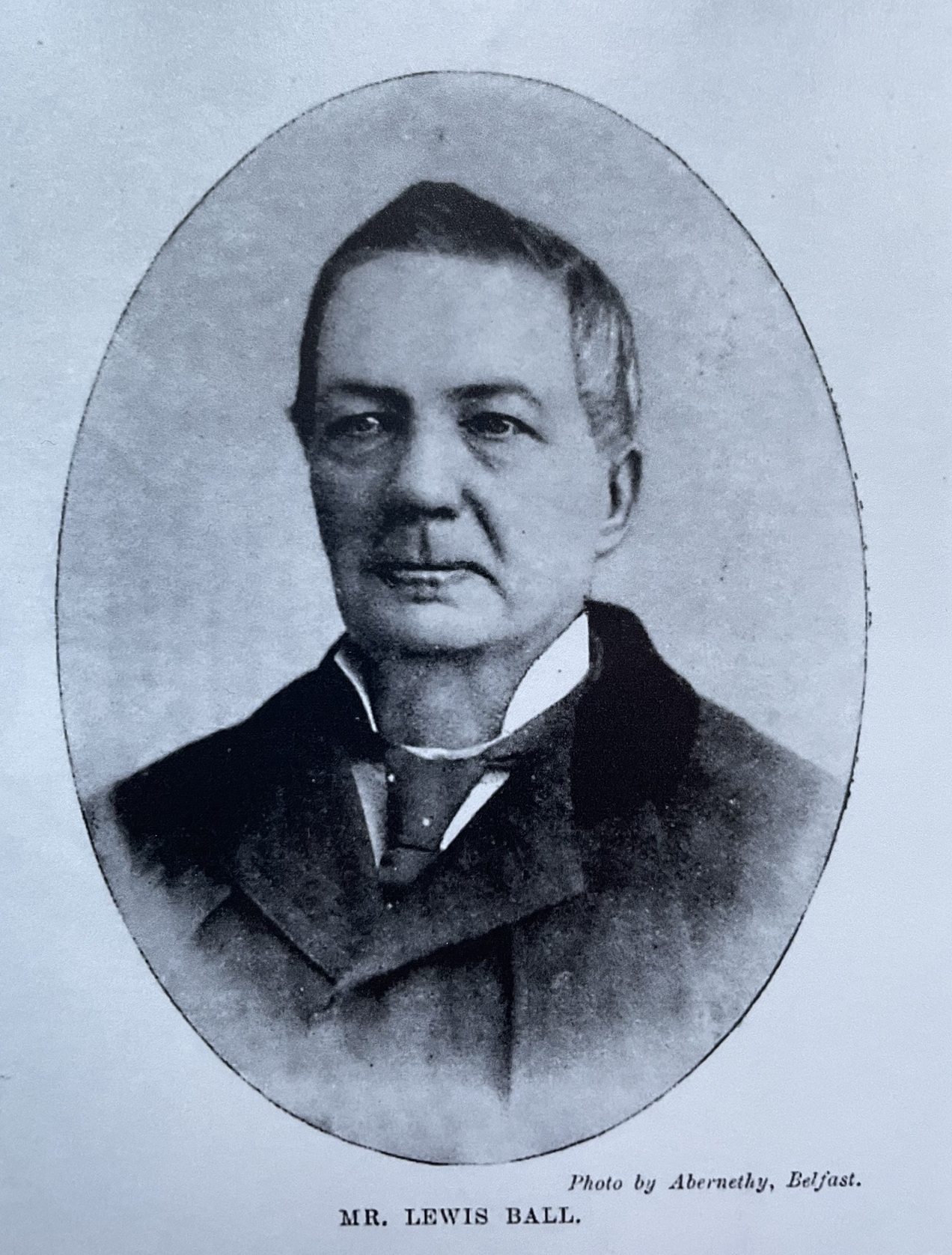

The story of Lewis Ball, the low comedian. He wasn’t a headliner but an accomplished supporting actor who had mastered the art of ‘low comedy’, equally comfortable on stage in a farce or a Shakespearean production.

Early Years

Lewis was born in Builth, Breconshire on 31st December 1820 to parents Richard Banks Ball and Mary Anne Ball. His father was described on Lewis’s baptism certificate as a ‘Comedian’. In fact he was more than just a comedian. In an interview in 1901 Lewis’s brother Meredith revealed that their father “in early life adopted the stage as a profession, and after going through the mill he eventually became manager of his own company of comedians with which he travelled through the towns in the north of England and Scotland and was a well-known figure in his day.”[5] He also recalls his mother as a ‘clever actress’ who, when his father died, “joined the Roxby circuit doing the Shields, Sunderland, Scarborough and other towns of the regular tours. She is still remembered by the old playgoer in those parts as Mrs Banks Ball.”

So it is perhaps no surprise that Lewis was destined for the stage himself despite the difficulties associated with the acting profession. As Meredith observed:

“The old prejudice against the stage was very powerful indeed. In my father’s days and, in deference to the wish of his parents who were Welsh, he abandoned his own name of Ball for Banks. The family thought that little less than absolute disaster would come upon them if it became known that they were in any way connected with the stage. The drama was the near cut to the bottomless pit and all who followed it as a profession were doomed irrevocably.”

Despite this Lewis made his first appearance at the tender age of two months when “he was carried before the footlights to impersonate the infant Elizabeth in Henry VIII at the little theatre in Morpeth. Mr. Ball doesn’t remember the incident himself, but he still treasures the baby fee of one shilling with which his mother was presented on the occasion – ‘the first honest shilling I ever earned’ he says.”[6] His mother played the part of the “gorgeously got up royal nurse, feeling wonderfully proud of her bairn, whose comic little face bespoke loyalty to Thalia.”[7]

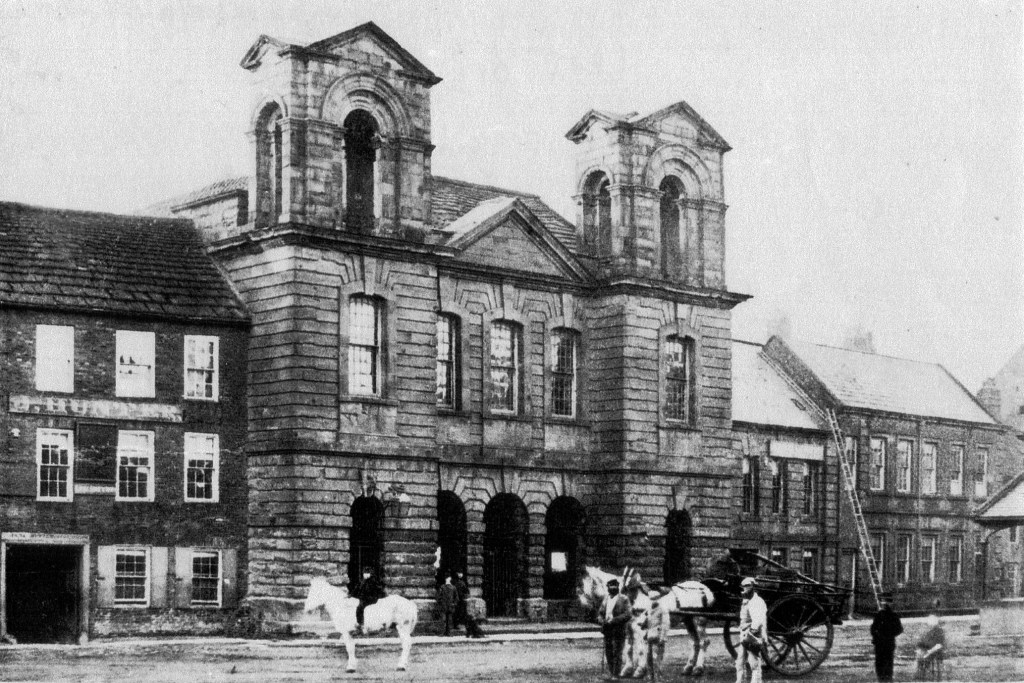

The touring, or ‘circuit’, companies such as Lewis’s father ran would move from week to week from place to place through the provinces and would end up performing in a variety of buildings. In the larger towns there could be purpose-built theatres emulating the grander theatres of London, such as the Theatre Royal Hull where Lewis had many performances. Other theatres were more makeshift such as the ‘little theatre in Morpeth’ where Lewis made his debut which was the town hall where the hall itself was made available for theatricals as and when required. Lewis himself recalls playing in ‘barns and inn parlours’ in his younger years.

According to Lewis’s autobiography[8] his first childhood acting recollection was playing Isabella’s child in ‘The Fatal Marriage’ in 1926. The heroine Isabella was played by Frances Kelly, coming up to Hexham fresh from her performance at Covent Garden. Lewis recalls “Miss Kelly taking me up in her arms, giving me a kiss and putting a coin into my hand, sent me to my Mother, who asked where I got it. I told her the Angel Lady gave it to me with a kiss, and I like the kiss the best.”

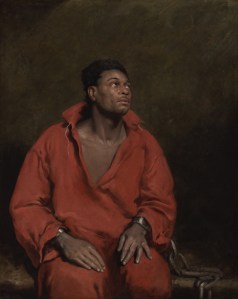

From a delightful kiss to a terrifying kiss in the next performance he remembers: “After her came the celebrated African Roscius, Ira Aldridge. I was the child in a musical drama called the Slave in which he played Gambia. I did not like him so well, for when he took me up to kiss me I screamed the house down.” Ira Aldridge survived the ordeal and went on to become a famous, if not always favoured (because of his colour), Shakespearean actor; he is the only actor of African-American descent honoured with a bronze plaque at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon.[9] [10]

So Lewis progressed from baby parts to child parts, young boy parts etc. gradually learning his craft on the circuits. By the time he was 18 Lewis remembers “living comfortably on fifteen shillings a week”[11] and being “fortunate enough to get an engagement with Messrs Moseley and Charles Rice at Huddersfield where I played Juveniles, Walking Gentlemen, Second Low Comedian, second old man etc. and danced character dances (as was then the fashion) between the pieces.”[12]

Being a Comedian was his destiny but I wonder if later in life he harboured any regrets about not being a great tragedian instead. As he confides in his autobiography “though everybody said I was cut out for a low comedian, and I played a good deal of the business, I had my own ideas on the subject and felt convinced that I was intended for a Tragedian, indeed the only one who would be able to supply the place of Edmund Kean, when vacant.” (Note: see also the Appendix ‘The Kean Coincidence’.

The Emerging Years

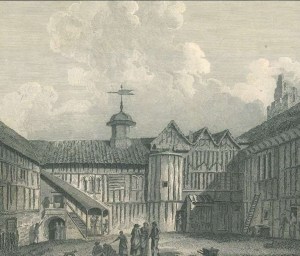

On Monday 5th May 1845 several performances were put on to a full-house at the Gainsborough theatre under the patronage of the Independent Order of Oddfellows and for the benefit of the Widows and Orphans’ Society. Amongst these was the Polka by Mr and Mrs Lewis Ball, which was encored.[13] The theatre was the converted old hall of the 14th century Gainsborough manor house.

This is the first reference I can find to the adult performances of Lewis Ball who by then had married Margaret Benson who, unsurprisingly, was also working on the circuits and was actually listed in the 1851 census as a ‘Comedian’ herself like Lewis. She had entered theatricals by a similar route to Lewis – her father William had been a member of the Roxby-Beverley theatrical companies well known in Shields, Durham, Scarborough, Sunderland etc.

Lewis’s recognition as a supporting actor had started to take off and over the next 50 odd years until his retirement in 1898 there are thousands of references to his performances all over the country. In this and the following sections there are merely a selection of these intended to give an inkling of how Lewis Ball was perceived and received as an actor.

By 1847 he had joined the acting company of actor/manager Mr John Langford Pritchard at the Theatre Royal Hull. Lewis described Pritchard as ‘a good hearted though most eccentric man, and having taken a great liking to me, he nearly worked me to death.’

Pritchard had an impressive track record and was sole director since 1842 of the York Theatrical Circuit. Lewis replaced the ‘principal low comedian’ Mr Gomersal: “Mr Lewis Ball, a gentleman apparently of more than mediocre talent, has joined the company. We remember his being very highly spoken of in our reports from Liverpool last summer. We have seen him play Long Tom Coffin in ‘The Pilot’ and should like to see his round of parts from the Muster Roll of Neptune.”[14]

With this Lewis had entered the pages of ‘The Era’, the longest running theatrical trade paper which has been described as ‘the actor’s bible’ by the theatrical historian W J McQueen-Pope. He had also been identified officially as a ‘low comedian’ or someone who practises the art of low comedy defined as:

“dramatic or literary entertainment with no underlying purpose except to provoke laughter by boasting, boisterous jokes, drunkenness, scolding, fighting, buffoonery, and other riotous activity. Used either alone or added as comic relief to more serious forms, low comedy has origins in the comic improvisations of actors in ancient Greek and Roman comedy. Low comedy can also be found in medieval religious drama, in the works of William Shakespeare, in farce and vaudeville, in the antics of motion-picture comedians, and in television.”[15]

Barely a month on Lewis lived up to The Era’s expectation when appearing in the play ‘The Challenge at Sea’ in which “The gem of the piece was Mr Lewis Ball’s Solomon Slyfox. This gentleman is an industrious, clever and versatile actor, and is an immense favourite as first low comedian and successor to Mr Gomersal.”[16]. It was at Hull also that Lewis was “much applauded for his active feats in ‘diablerie’” …. Or the quality of being wild or reckless in a charismatic way!!

His abilities were equally recognised at the Theatre Royal York six months later where in a performance of the romantic melodramatic ballet ‘Daughter of the Danube’ he “was called before the curtain to receive the congratulations of the audience”[17] In a reprise of this barely a week later in Hull – “the extraordinary performance of Mr Lewis Ball eliciting the most rapturous applause.”[18]

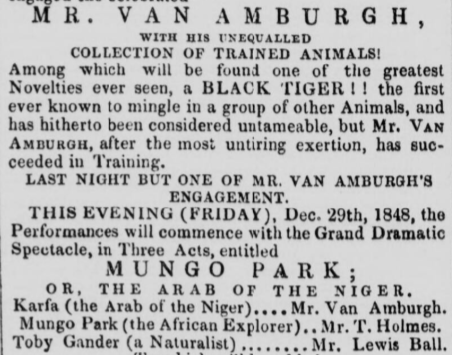

Pritchard was keen to “afford his Hull Patrons and Visitors every variety of Amusement in his power” but even Lewis must have been daunted when required in December 1848 to play the part of a naturalist, Toby Gander, in the ‘Grand Dramatic Spectacle’ of Mungo Park with Mr Van Amburgh and his collection of trained animals, including a black tiger[19].

Lewis obviously survived the challenge and went from the ridiculous to the sublime barely a month later with what appears to be his first referenced role in a Shakespearean play since he was a baby. He played the part of Roderigo in Othello and showed himself to be “an actor of just discrimination. It is some time since Roderigo was played so effectively as Monday evening.”[20]

And so the accolades continued …..

“Mr Lewis Ball has well nigh attained the power of greater men by name – the power of making one laugh not at him but with him.”[21]

“Mr Lewis Ball is naturally a clever performer and his humour has the rare merit of often appearing spontaneous”.[22]

“In the farces Mr Lewis Ball and the lessee (Mr H. Beverly) have been the most prominent as they are two of the most clever of the light comedians now on the provincial boards”.[23]

In August 1850 John Pritchard died and the management of the Theatre Royal Hull and the York theatrical circuit was taken over by a Mr John Caple. At some point after that Lewis also took on the role of stage manager at the Theatre Royal Hull and by 1852 also earned what appears to be his first benefit performance. Up to the end of the 19th century actors were usually hired on a one or two year contract and may have an additional ‘benefit’ performance in which the actor would be entitled to all or part of the proceeds. Effectively it became a mark of the actor’s success or popularity.

The Hull Daily News had no doubt this would be a ‘bumper’ benefit: “Considering the marked improvement which the habitues of the theatre have noticed in the manner in which pieces are place on stage since this gentleman accepted office and the favourable position which his excellent acting and broad humour has obtained from him in the York circuit, both in this and a previous management, we have little doubt but that his efforts will be rewarded on Monday night by a ‘bumper’”.[24]

This was confirmed after the event in which his wife also appeared:

“Sterne, in his dedication of Tristram Shandy, observes that he is ‘firmly persuaded that every time a man smiles- but more so when he laughs – it adds something to this fragment of life.’ Now, if this be true, a large number of the good people of Hull must have added pretty considerably to the duration of their existence in this sub-lunary sphere on Monday evening last when Mr Lewis Ball took his benefit at the Theatre-Royal. For his irresistible drollery did not merely provoke occasional smiles but well nigh kept the audience in a continued burst of laughter every time he made his appearance on stage. The pieces selected were ‘The Flowers of the Forest,’ in which Mr Ball was Cheap John; ‘Like Master like Man’ in which he personated Sancho; and ‘Your Life’s in Danger’ in which he appeared as John Strong. Mrs Ball appeared in the first piece as Starlight Bess. There was an ease and elegance in her impersonation of the gypsy which bespoke a careful study of the part and we have no hesitation in saying that she was completely successful.”

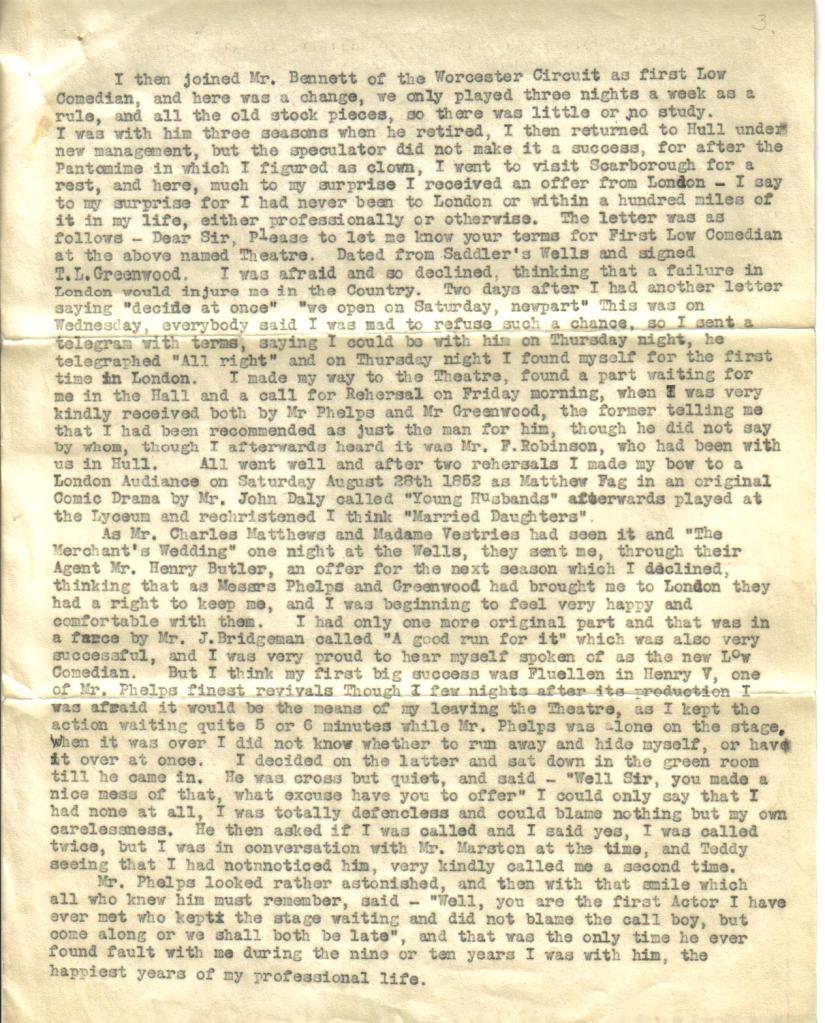

Some six months later Lewis had left the provinces and joined the prestigious company of Samuel Phelps at the Sadler’s Wells theatre in London. It is said that any actor worth their salt at that time aspired to appear in London theatre but Lewis almost didn’t make it as he explained in his own words:

“Much to my surprise I received an offer from London – I say to my surprise for I had never been to London or within a hundred miles of it in my life, either professionally or otherwise. The letter was as follows – Dear Sir, Please to let us know your terms for First Low Comedian at the above named Theatre. Dated from Saddler’s Wells and signed T.L.Greenwood. I was afraid and so declined, thinking that a failure in London would injure me in the Country. Two days after I had another letter saying ‘decide at once. We open on Saturday. New part.’ This was on Wednesday, everybody said I was mad to refuse such a chance, so I sent a telegram with terms, saying I would be with him on Thursday night. He telegraphed ‘All right’ and on Thursday night I found myself for the first time in London. I made my way to the Theatre, found a part waiting for me in the Hall and a call for Rehearsal on Friday morning ….. All went well and after two rehearsals I made my bow to a London Audience on Saturday August 28th 1852 as Matthew Fagg in an original Comic Drama by Mr John Daly called ‘Young Husbands’.”

So Lewis must have felt it to be a great personal honour to be accepted into that arena where he was soon to make his mark, now a ‘first’ low comedian, and building on his experience in a wide range of Shakespearean roles. As he says in his autobiography “before I came to London I had been on for every part, good or bad, from the Duke of York upwards in Richard the Third, Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth, the title role and ladies of each alone excepted, and I think there are few actors left who have gone through all that.”

The London Years

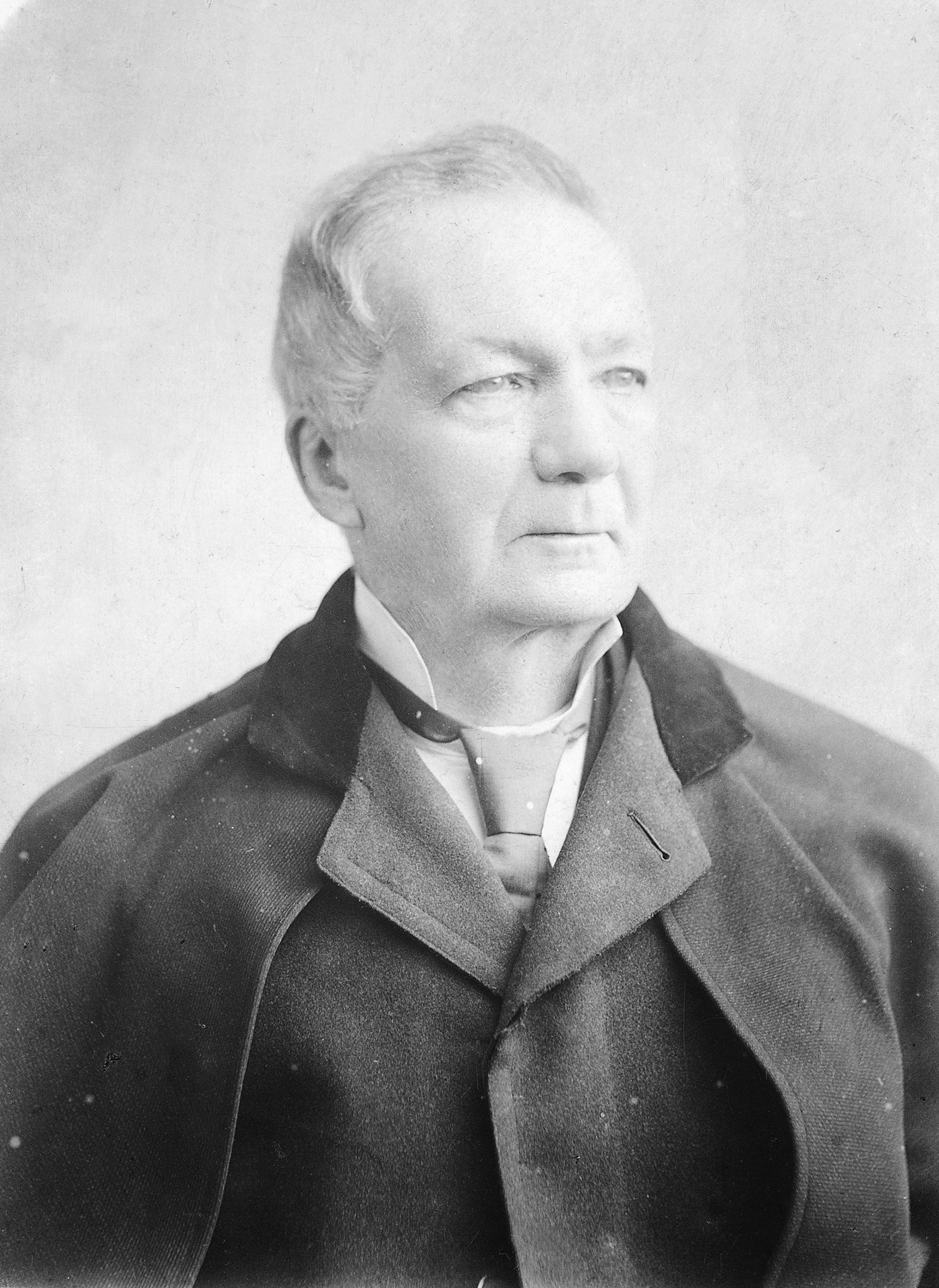

One of the oldest theatres in London Sadler’s Wells started in the 1680s but apparently did not have the requisite licences for theatrical performances; so it languished until the early 19th century when Samuel Phelps grabbed it by the scruff determined to turn it into the leading London theatre. In the early part of the century Phelps was considered one of the finest Shakespearean actors of his time, competing with Edmund Kean early on for the accolade of ‘greatest’ of that period. He acquired the lease for the theatre in 1844 and over the next 17 years worked to realise his ambition.

He set high standards for both himself and the company. Lewis experienced this when on one occasion he missed his call and kept Phelps waiting on the stage for five minutes; he was appropriately reprimanded and probably never let it happen again.[25] (Note: See the Appendix on the ‘Green Room Incident’).

Making his mark

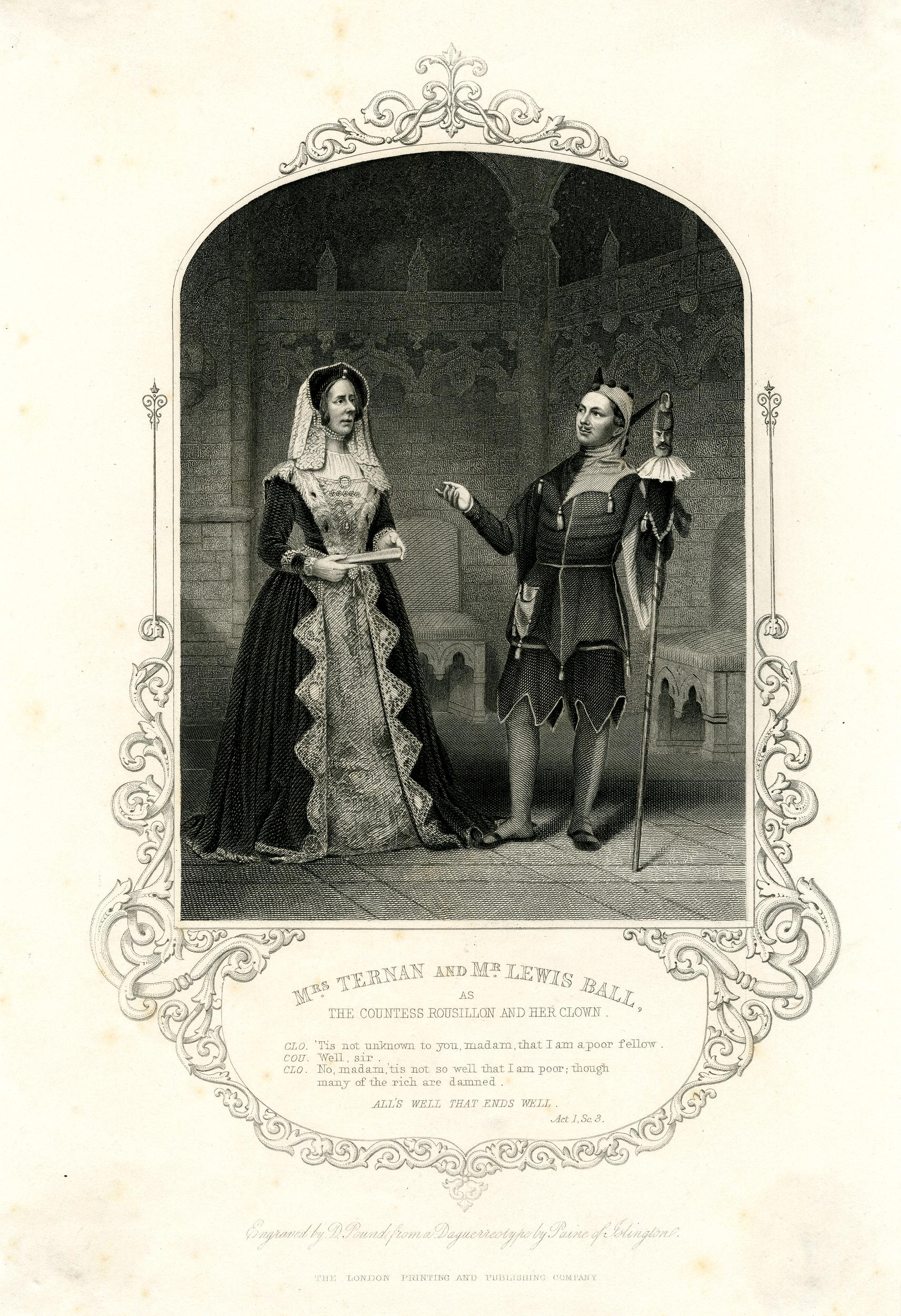

After his debut in ‘Young Husbands’ Lewis was soon on stage again for the first night of ‘All’s Well that Ends Well” in which he played the part of the Clown to Fanny Ternan’s Countess Rousillon. The play was well received: “The applause at the conclusion was rapturous and Mr Phelps was called to receive the vehement approbation of the audience.” Lewis had his first mention in dispatches being described as “quaint and pointed as the clown”.[26] This also provides us with the first and one of the few opportunities to see a picture of Lewis Ball – he was portrayed with Mrs Ternan in the playbill. This was a rare event because Lewis did not like being portrayed (or, later, photographed), as he later explained to photographers.

He soon moved on to meatier stuff, playing the role of Captain Fluellyn in Henry V. The role was an important one as emphasised in the subsequent critique: “Fluellyn lightens up to some extent the latter acts; and the scene between the honest, simple soldiers and the disguised king the night before the battle of Agincourt, is not only full of pregnant thought, but the only one in which Henry is introduced which boasts of the slightest infusion of the dramatic element.” Lewis’s portrayal of Fluellyn was “pert, jaunty, lively, and contained from first to last a definite picture of the hot-headed, quick-brained Taffy which was a great relief from the stately lords and dukes. There was a sparrow-like vivacity about Mr Ball’s Fluellyn which adequately brought out the quicksilver restlessness of the conception.”[27]

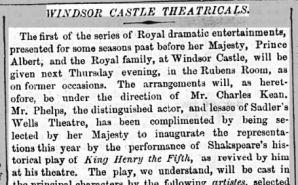

Command Performances

The play was referred to as one of Phelps’s finest revivals and was rewarded in November 1853 by a Command performance at Windsor Castle in front of Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort. Lewis was there in the part of Fluellyn and “at the conclusion of the performance the congratulatory message of her Majesty included a clause to the effect that she was especially delighted with ‘’the Welshman’ and she wished the gentleman who played the part to know it.” [28] As a result of this Lewis was christened the ‘Pet of the Palace’!!

Lewis was also part of the festival performances and a second Command Performance marking the marriage of the Princess Royal to Prince William Frederick of Prussia in 1858.

Building his portfolio

By this time Lewis had built up an impressive portfolio of parts either at Sadler’s Wells or on tour with the company in the off-season. These included:

In Hamlet: “Mr Lewis Ball made the hits in the First Gravedigger with his usual ability and judiciously shunned the vulgar waistcoat trick”.[29]

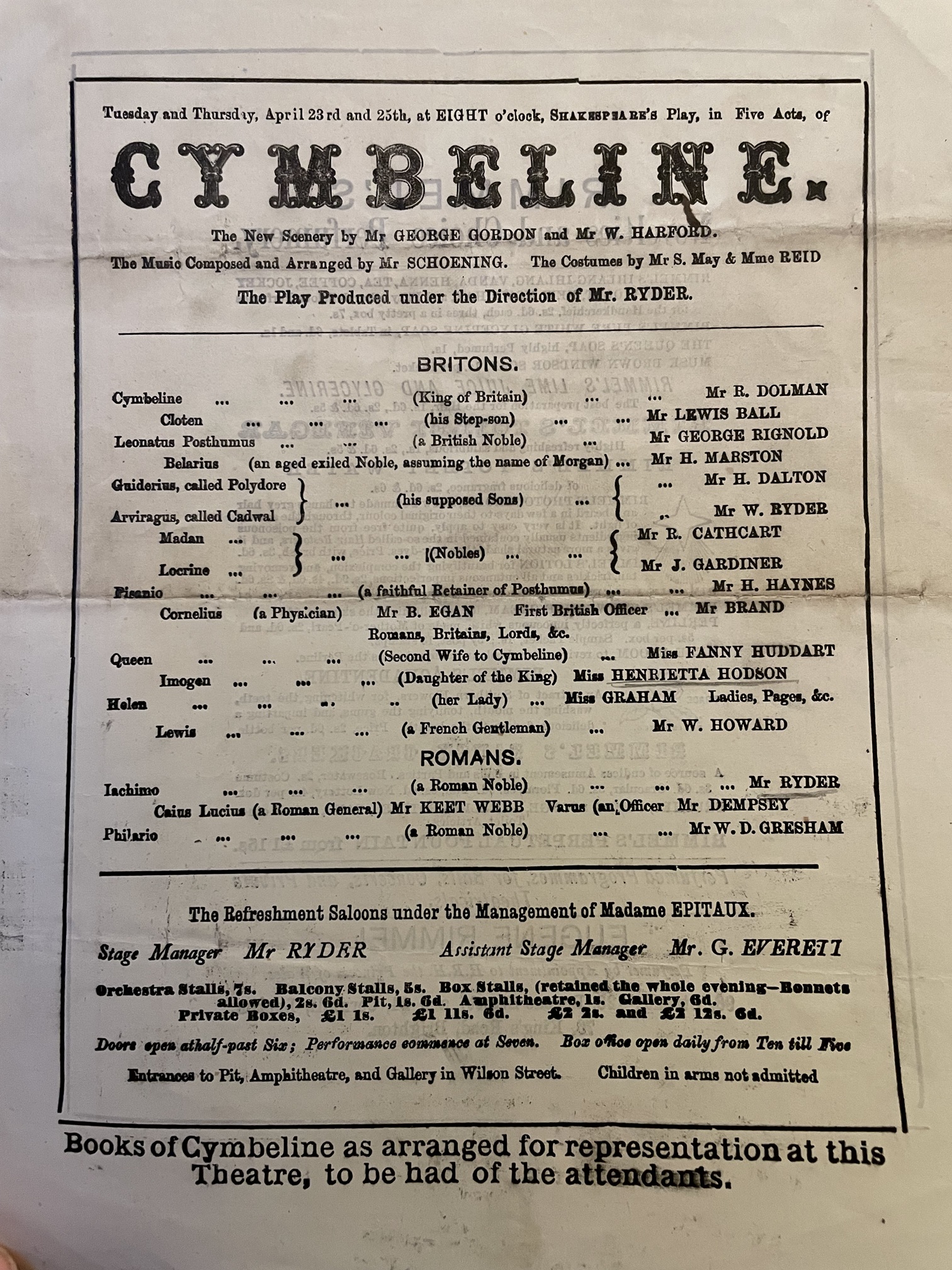

In Cymbeline: “We were much pleased with Mr Lewis Ball’s Cloten which, without caricature, was effective.”[30]

In The Comedy of Errors: “the Dromios, which are essentially of the ‘screaming farce nature’ were very well acted by Mr Fenton and Mr Lewis Ball”.[31]

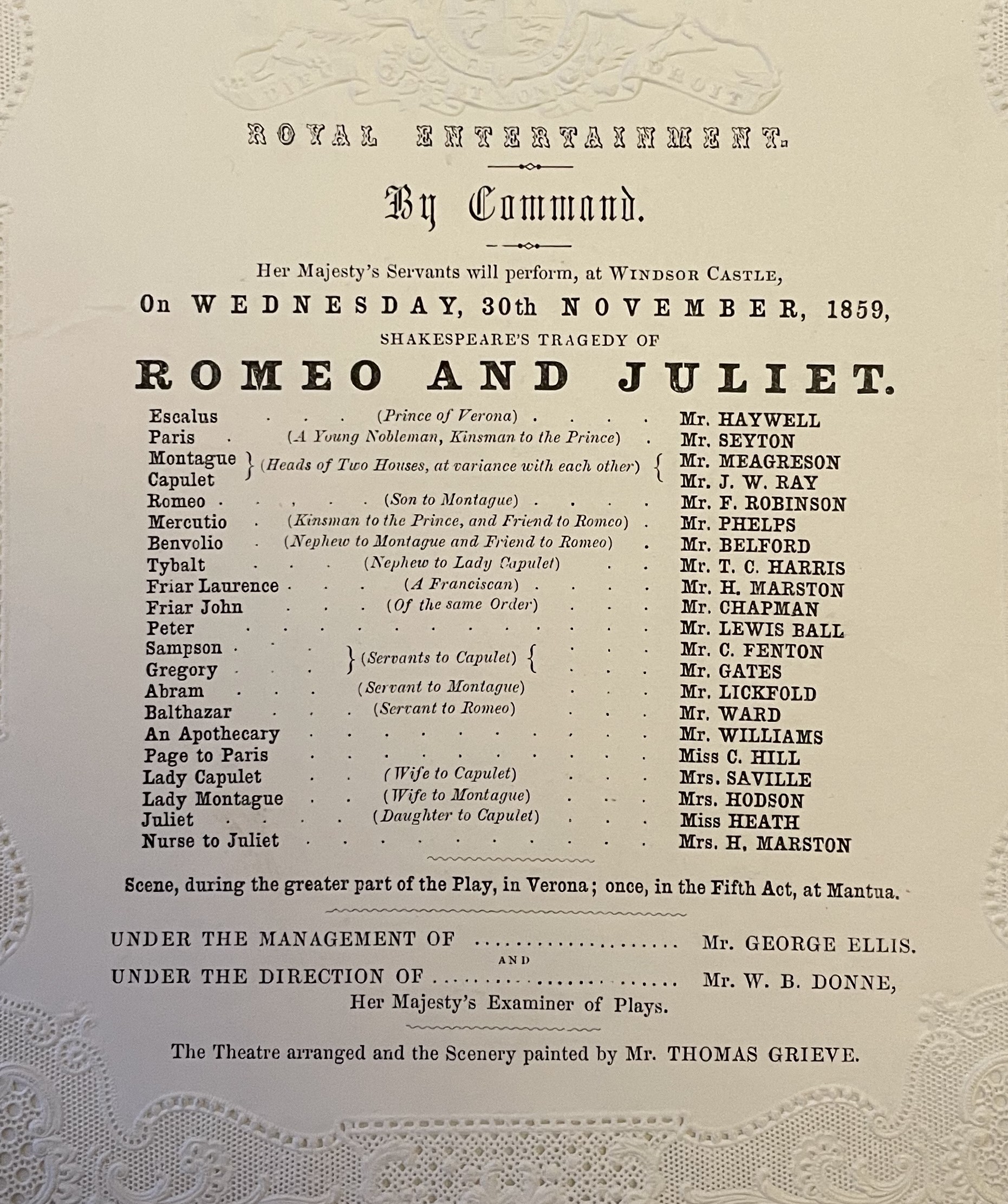

In As You Like it as Touchstone; The Merchant of Venice as Launcelot Gobbo; The Winter’s Tale as Clown’; The Tempest as Trinculo; Macbeth as one of the three witches!!; Coriolanus as first citizen; Romeo and Juliet as Peter.

And …. having debuted in the play as a two-month old baby Lewis returned to Henry VIII in the part of Lord Sands: “Mr Lewis Ball in the traditional comic part of Lord Sands advantageously contributed to a generally efficient cast.”[32]

It appears that tragedies such as Macbeth were often followed by the dessert of a comical piece to lighten the mood at the end of the evening before playgoers departed. One example of this was: “The lively farce by Charles Dance of ‘Advice Gratis’ was the afterpiece, in which Mrs Marston and Mr Lewis Ball appeared to great advantage and caused the audience to leave with a pleasant conviction that for many months to come they were sure of having in their own immediate locality the means of securing a highly refined and intellectual evening’s enjoyment.”[33]

Lewis may have displayed a professional persona of confidence but in his autobiography he confesses to a ‘terrible nervous fear of a London Audience and a London Press’ which he says continued until a notice appeared in the Times of 26 October 1857: “Mr Lewis Ball has become the recognised impersonator of Shakespearean clowns, and by the quaint pomposity and sham wisdom of his Touchstone he shows his right to his calling”.

1858

In 1858 his wife performed in Cambridge with the Cambridge Amateur Theatrical Society to help raise funds for the Indian Relief Fund. 1858 was also the year of an experiment at Sadler’s Wells where a trial run of English Opera in April was so successful that it was continued; Samuel Phelps effectively took a sabbatical for a year, touring the provincial theatres of the UK and throughout Europe, and members of his company moved elsewhere.

By June that year Lewis had joined the Olympic Theatre: “At the Olympic Theatre on Monday the farce of The Cabinet was produced to introduce Mr Lewis Ball who has acquired a high reputation in playing the Shakespearean fools at Sadler’s wells. Mr Ball has such humour and a thorough perception of character and must prove an acquisition to any company.” [34]

After a month he must have wondered whether he had made the right move after this scathing review: “anything more bad in the way of a farce than the Windmill we do not know. It seems to have been revived for the especial behoof of Mr Lewis Ball, who certainly does his best for Sampson Low, but the best that can be done for that stupid and uninteresting young man is something too infinitesimal to be recognised. He has red hair, knee breeches, and says ‘dang it’; and that is all that need be said about him.”[35]

It was a mixed year for Lewis and he confessed that he did not feel comfortable at the end of it. He survived though and it must have been with some sense of relief to him that in May 1859 Sadler’s Wells re-opened under Phelps and Lewis returned to his former position of first low comedian. He was back at Windsor Castle for another Command performance in December playing the part of Peter in Romeo and Juliet.

The Doldrum Years

An era ended in March 1862 when Samuel Phelps retired from his role as director of Sadler’s Wells, took his benefit performance, arranged a number of other benefit and charitable performances for members of his company and then handed over the reins to Miss Catherine Lucette. Lewis described the nine or ten years he had spent with Phelps as the happiest years of his professional life. In a letter Lewis wrote in 1899 to the theatre historian Scott Clement he says: “I always look back in pride and pleasure to the many happy years I spent under the management of Mr Phelps, to whose kindness, indulgence, and instruction I owe so much.”[36]

The departure of Phelps was the start of turbulent times for Lewis. A year later the management passed over to Miss Marriott who had “a very strong company which is well-fitted to restore the old-fashioned animation to Sadler’s Wells. Good as were the endeavours of Miss Catherine Lucette … the entertainment they provided was scarcely strong enough for the cultivated legitimate appetite.”

All of this appears to have had an impact on Lewis. It looks as though he had had enough of London theatre life and had decided to return to acting in the provinces. After a stint at the Theatre Royal in Scarborough (where he appeared alongside the ‘Ghost Illusion’!!)[37] he joined up again with Catherine Lucette and Morton Price who had formed the London Dramatic Company based that winter (1863) out of the Theatre Royal Gloucester. The Company would move from one town to another but often taking on the management of the theatre in each town so that there was relative stability for the actors over a season. Lewis seemed to have settled in with the new company and was still pulling in good comments such as this from the Theatre Royal in Huddersfield in 1866: “Mr Lewis Ball, always well up in his part, did not loose caste last evening. His representation of Hunchback in the Lottery Ticket … it is scarcely possible to surpass.”

There is an impression though that the next 14 years was a more unsettled period for Lewis. There are far fewer references in the press to Lewis’s acting with occasional criticisms perhaps caused more by having to perfom roles for which he was not suited: “Of Mr Lewis Ball, as Bob Brierly, we cannot say much; comedy is his forte, and there is too much of the tragic element in Bob Brierly; in fact he was over-weighted.”

A large part of his touring time was with Morton Price but this was interspersed with stints in London at the City of London theatre and Sadler’s Wells and other tours with the Anglo-American Combination Company (Catherine Lucette), the Varieties Comedy-Drama and Burlesque Company, and the London Company (Miss Marriott). In the last five years of this period it seems that Lewis increasingly spent more time in management roles – director, stage manager, business manager, theatre manager have all been mentioned particularly at the Theatre Royal, Leicester.

Family changes

It was also a time of changes in his family. In 1869 his father-in-law William Benson died.[38] On a more upbeat note his third daughter Cicely married Samuel Henry Culley in January 1875. But then five years later Lewis was struck by the death of his wife Margaret aged only 56; she was buried in a ‘common grave’ in Highgate Cemetery.. Lewis must have been devastated but he was already committed to the ‘Hatred’ tour through May and June and the show must go on; there are no further press references to Lewis Ball in the second half of 1880.

The Revival Years

In December 1880 a new Company was formed – the ‘Compton Comedy Company’: “Mr Edward Compton is now arranging a Spring Tour during which he will appear as Malvolio, Touchstone, Dr Pangloss, Ollapod, Mawworm, Acres, Tony Lumpkin, and other Parts in the old Comedies, especially associated with the name of his late Father, accompanied by a High-class Company. Dates already arranged for Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dublin, Liverpool.”[39] By February 1881 Lewis had joined up with a dual role as a member of the cast and stage manager.[40]

Success!

The Spring tour was successful and the Company continued. At age 60 Lewis seems to have found a new lease of life and he remained with the Company until it finally disbanded 17 years later. The Company’s success was marked in Belfast in 1886 at a grand supper party to celebrate its fifth anniversary. Lewis proposed the toast:

“Mr Lewis Ball, stage-manager, in a speech abounding alike in eloquence and humour, proposed the Compton comedy company. Mr. Ball has been a member of the company from the date of the initial performance at Southport, February 7th 1881, and much interest was excited by his vivid description of the managerial anxiety attending it and the prognostications of failure which circulated in professional circles as likely to attend Mr Compton’s attempt to popularise old English comedy in the provinces, and which had been so gratifyingly falsified by the success, increasing in a ratio from year to year, of the experiment apparently so rashly made.”[41]

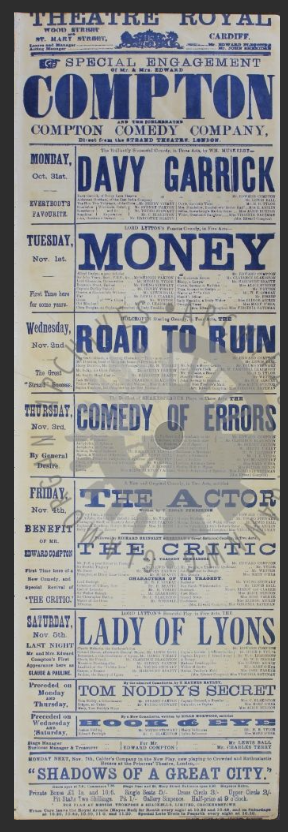

Life must have been highly pressurised in such a travelling company. A playbill from November 1887 for example shows them performing six different plays (plus additional ‘comediettas’) on consecutive nights: Monday October 31st – Davy Garrick; Tuesday – Money; Wednesday – The Road to Run; Thursday – The Comedy of Errors; Friday – The Actor; Saturday: Lady of Lyons.

Recognition

Once again we start to see recognition of his performances appearing in the various provincial and national reviews. Here’s a small selection over the period:

| In 1881 in George Coleman’s ‘Heir-at-Arms’ at the Memorial Theatre Stratford | “Daniel Dowlas, who succeeds to the peerage from the supposed loss of the son of Lord Duberly, found an excellent representative in Mr Lewis Ball. The humour of the character was capitally brought out and some of the scenes … were provocative of much laughter. The vulgarity of speech of the old Gosport shopkeeper was so skilfully toned that even the most fastidious could not help enjoying it.”[42] |

| In 1886 in ‘Twelfth Night’ at the Royal Theatre Greenock | “Mr Lewis Ball as Sir Toby in The Twelfth Night again made the house ring with peals of merry laughter, and in all his parts confirmed previous successes.” [43] |

| In 1886 in The Rivals at the Strand Theatre | “The bouquet and full, rich flavour of old comedy had an excellent exponent in Mr Lewis Ball whose ripe, experienced acting as Sir Anthony Absolute was so admirable that it cast the other players into the shade. In a company such as Mr Compton’s, where so many members are youthful, Mr Ball is invaluable. He has the traditions of the stage at his fingers’ ends, but he is no barn-stormer or ranter. The maturity of his acting, which has begotten in him a quiet, natural manner and confidence affords a good study to all stage aspirants.”[44] |

| In 1891 in ‘School for Scandal’ at the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh | “The play is one which suits the Compton Comedy Company admirably, and it was produced with a completeness and success that left nothing to be desired. Mr Lewis Ball made, as usual, an excellent Sir Peter Teazle, every feature of the character being faithfully portrayed; while the little tiffs between him and his young wife were carried through in a most enjoyable spirit.”[45] |

It was in 1891 also that an unfounded rumour in the press of the ‘death of that admirable comedian Lewis Ball’ prompted a short ditty to allay the fears of audiences:

“If Lewis Ball were heard no more,

Thalia would the loss deplore.

The news is, therefore, most consoling

That Ball’s alive, and still keeps rolling.

In 1896 the Freeman’s Journal talks about Lewis’s appearance at the Gaiety Theatre, Dublin: “It is not easy to speak about Mr Lewis Ball. He is now without exception the finest type of the old man on the stage. But he is something even more than that. He is the greatest and the best link that connects the old school with the present, and all Dublin lovers of the drama have come to welcome the presence of the Compton Company in no small degree because it has brought with it the great privilege of seeing and hearing Mr Lewis Ball. As Alderman Gresham he, of course, was perfect and his slight physical failing was witnessed with sympathy by an audience whose appreciation of his gifts is derived from years of enjoyment to which he has so much contributed.”

Retirement

And so we come to 1898, the year when the Compton Comedy Company disbanded and Lewis decided that it was finally time to retire. By this time there was speculation on whether he was the oldest actor on stage. For some there was no doubt: “The Nellie Farren benefit has excited a controversy as to who is the oldest actor on the stage. The position is claimed for Mr Lewis Ball, brother of Mr Meredith Ball, Sir Henry Irving’s musical director. As far as London is concerned Mr Lewis Ball’s position is incontrovertible. He is seventy-eight years of age and boasts a practically uninterrupted theatrical career of seventy-seven years.”[47]

The Company’s final tour in April/May that year led to plaudits to Lewis throughout. Here are just a few examples:

Dublin, The Gaiety: “Mr Lewis Ball, who has been so long connected with the Compton Company, received a thrilling ovation when he made his appearance in the part of Alderman Gresham. In the interpretation of this and similar parts Mr Ball is incomparable, and yet the warm welcome given to him last night was not less an appreciation of his artistic ability than it was a demonstration of the personal regard that every patron of the Compton Company feels for the distinguished old actor.”[48]

and ….. “Mr Lewis Ball as Sir Anthony Absolute surpassed himself, if possible, as he entered spontaneously into the humour of the familiar scenes, exciting the audience to uncontrollable laughter.”[49]

Leeds, The Grand: “The performance of the ‘School for Scandal’ at the Grand last night was remarkable for ….. the wonderful acting of Mr Lewis Ball as Sir Peter Teazle ….. the pit rose at him.”[50]

Newcastle, Theatre Royal: “Of the Alderman Gresham of Mr Lewis Ball it is hardly necessary to say more than we have herein a fine specimen of a school of acting which we are afraid is fast dying out, to the great loss of British art.”[51]

Bradford, Theatre Royal: “Mr Lewis Ball ….. has seen 78 summers and is therefore fully qualified to play ‘old men’s parts.’ As a matter of fact, however, Mr Ball is quite sprightly and juvenile, and shows no sign of having reached the last stage of what Shakespeare in the Seven Ages terms ‘that strange, eventful history’.”[52]

Dublin’s farewell to Lewis was probably the most effusive though: “The reception given to Mr Lewis Ball during the present week has been of a kind that few actors of our day can boast of. Opinions may and invariably do differ as to the particular merits of this or that exponent of ‘Hamlet’, but no rival has yet wrested from Mr Ball the position of the best and first old man on the British stage. He has been properly called the Nestor of the English Stage, and to the Compton Comedy Company he has been a tower of strength. His power and capacity are great, remembering that he has three-quarters of a century stage experience. He is close on eighty years of age and so far back as the time of Phelps he made a phenomenal success as Shakespeare’s clowns. As was said in effect recently by an influential English journal, one of the greatest regrets of provincial playgoers on hearing of the impending disbandment of the Compton Comedy Company was the probable loss of this old favourite. During the past sixteen years Mr Lewis Ball has found congenial occupation as ‘First old man’ and stage manager of this powerful organisation, a dual role that would try the strength of many a younger man. In parting with him this week every Dublin playgoer will heartily re-echo our wish for the continued health and happiness of one who has so often contributed to their enjoyment.”[53]

He had lived through a period of great change in the acting profession – he had “lived long enough to see the actor emerge from the ‘rogue and vagabond’ cloud and become a popular and courted member of society. He knew all the drawbacks and disadvantages, the hardships, the struggles and the privations of the player, and he realised the difference between the rate of remuneration in the first and that in the last half of the nineteenth century.”[54]

Retirement was initially to his home in Essex but when his daughter Annie and her husband George Bilton took over the management of the London Hotel in Teignmouth he moved down to join them there for his last few years. He died on 14th February 1905. There were many obituaries published in the press at the time mostly cataloguing his prolific acting career in which he supported so many of the leading stars of Victorian theatre. As the Greenock Telegraph succinctly put it: “Thus did our good old actor graduate among the ‘stars’ – a perfect constellation of them. The boards never knew a more modest artist. He made all his points without staring at his audience and endeavouring, as some do, to quicken popular applause.”[55]

Little is known about his life in Teignmouth but the Teignmouth Post did make the following comment: “By his bright and extremely pleasant companionship Mr Lewis Ball ….. has made many friends and numerous acquaintances in our town who will learn with the greatest regret that that grand old comedian passed away there at the ripe old age of eighty-five years. Whilst Mr Ball’s death cannot be said to be altogether unexpected, it is a matter of comment that his faculties were bright up to within the past four weeks, and that right up to the morning preceding his decease he was as chatty and conversational as ever. Personally he was most modest and retiring, never would be interviewed, and much to the disappointment of London photographers never would commit to have his portrait sold. He would say with his peculiar sweet smile ‘No thankyou; people may pay to come and see me act but I am not going to be bought for a shilling.’”[56]

He did consent though (possibly as a cheeky riposte to those London photographers?!) to a personal photograph being taken shortly before he died, by the photographer Sidney H Clamp of The Triangle, Teignmouth.

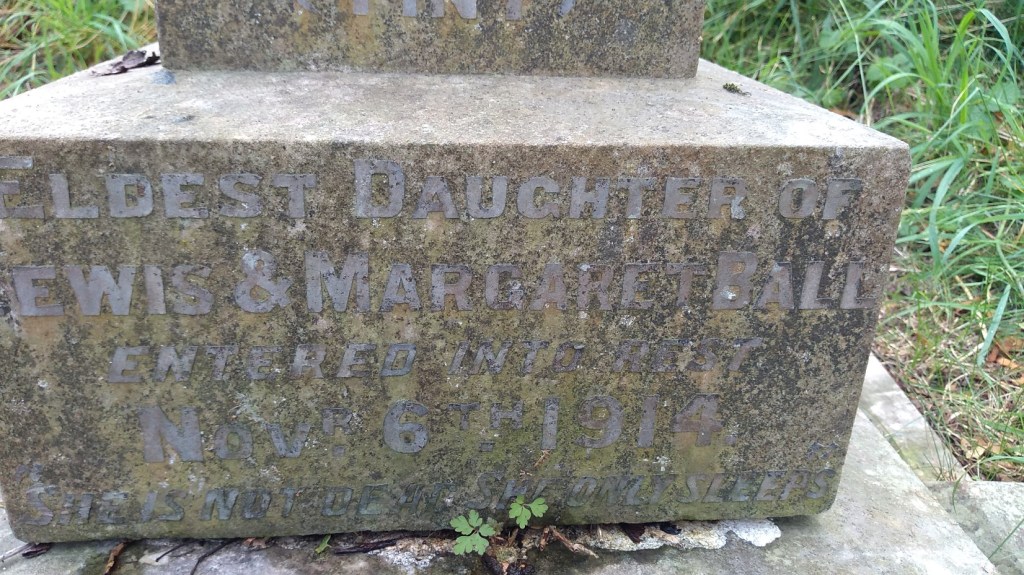

It was here in Teignmouth that he was laid to rest on Saturday 18th February 1905 “in the peaceful shades of the little cemetery at Teignmouth where the Channel waters lap the Devon shore” [3]

There was an abundance of floral tokens, many with a profusion of primroses – Lewis’s favourite.[57] The tribute from his eldest daughter Mary was these lines from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet:

“O woe, thy canopy is dust and stones,

which with sweet water nightly I will dew;

or, wanting that, distilled by moans,

the obsequies that I for thee will keep

nightly shall be to strew thy grave and weep.”

On hearing of his death Sir Henry Irving telegraphed his family “May I beg you in your sorrow to accept my respectful and deep sympathy? Your father was loved and honoured by all who knew him.”[4]

Lewis was buried in what would become a family grave (double plot T127/128) for his eldest daughter Mary Anne ,‘Tiny’, (6 Nov 1914), his youngest daughter Annie (19 Aug 1922) and her husband George Bilton (20 Oct 1940). His wife Margaret is also remembered as is Annie and George’s son Lewis, 2nd Lt, who died in Loos, France, May 1917.

The verse below Lewis Ball’s name on the headstone is a curious contrast to the Shakespearean tribute; it is relatively modern for the time, being written only nine years earlier in 1896 by Mark Twain. I wonder who might have known the poem and selected it. Was it Annie who had the poetic interest? At age 19, billed as the daughter of Lewis Ball, she had appeared on stage reciting poetry in ‘A Grand Dramatic and Musical Entertainment’[58] performed by Isledon Dramatic Club.

Warm summer sun, Shine kindly here,

Warm southern wind, Blow softly here.

Green sod above, Lie light, lie light.

Good night, dear heart, Good night, good night.

Rest in Peace Lewis Ball, low comedian

Acknowledgements

A big thankyou to Johanna Cotter, the great-great-great grand-daughter of Lewis Ball who has provided the wonderful personal pictures, a copy of Lewis’s own short autobiography and insights into Lewis’s personality from memories handed down. Also thanks to John Bibby of the Morpeth Antiquarian Society who checked their archives for any details of Lewis’s first performance and supplied the picture of Morpeth town hall where theatrical productions were performed.

APPENDICES

A1. Lewis’s Appearance with Ira Aldridge

The obituaries of Lewis Ball make reference to his appearance on stage as a three-year old (so around 1823/24) playing the part of the son of Cora in Sheridan’s play Pizarro. He remembered being held aloft by the actor Ira Aldridge. But this contradicts Lewis’s own account in his autobiography, and the timeline doesn’t add up.

Ira Aldridge was a 17-year-old black actor who had emigrated from New York to Liverpool in 1824. He had made his acting debut in Pizarro at the African Grove Theatre in New York playing the part of Rolla in whose role he would indeed have raised Cora’s child aloft. However, I can find no definitive evidence that Ira Aldridge either played the role of Rolla, or indeed acted in Pizarro in the UK around the time that Lewis was three.

When he arrived in Britain, as well as acting in his own name he took on pseudonyms, one of which was ‘The African Roscius’. Under this name he did perform as Rolla in Pizarro but in 1827[59] when Lewis would have been six. This would have been on the same tour as when he played Gambia in ‘The Slave’, which is what Lewis recalls.

The position is further confused by the interview which Lewis’s brother Meredith gave in 1901 in which he is reported as saying “My brother Lewis Ball tells me that my next part was as Cora’s child in Pizarro – a play that is rarely heard of nowadays but which was highly popular years ago.” The play was certainly doing the rounds in the early 1840s which is when Meredith would have been two or three years old.

Ira Aldridge went on to become a famous, if not always favoured (because of his colour), Shakespearean actor and is the only actor of African-American descent honoured with a bronze plaque at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon.

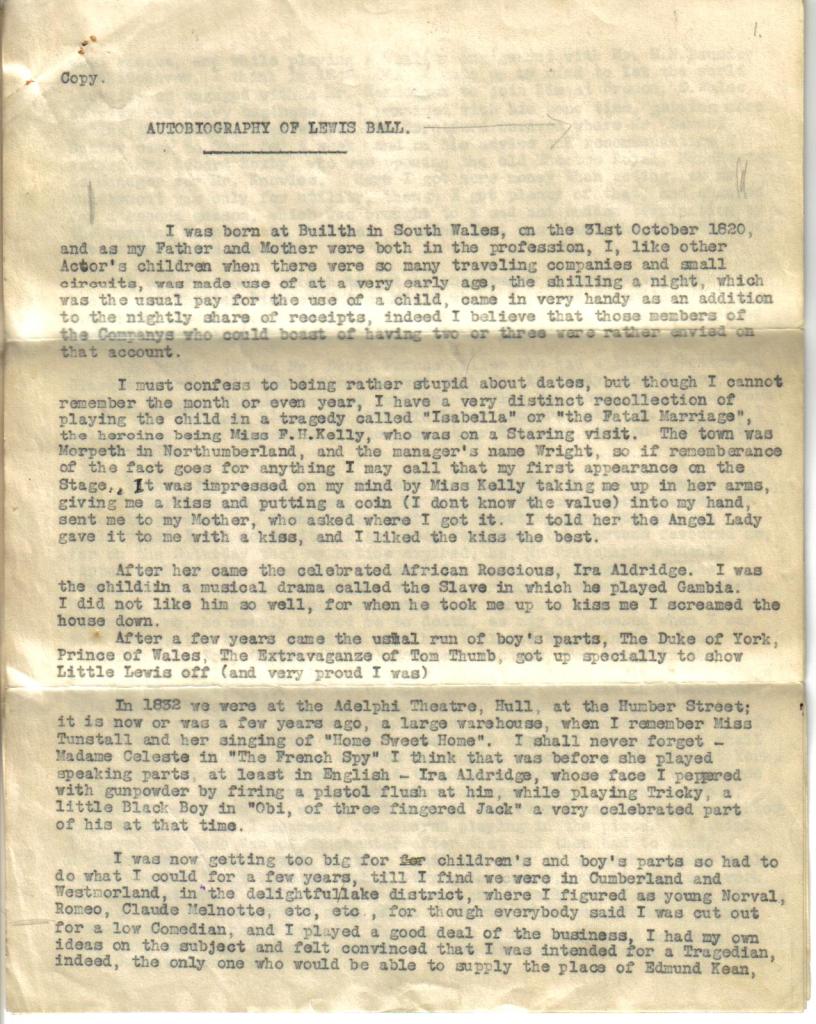

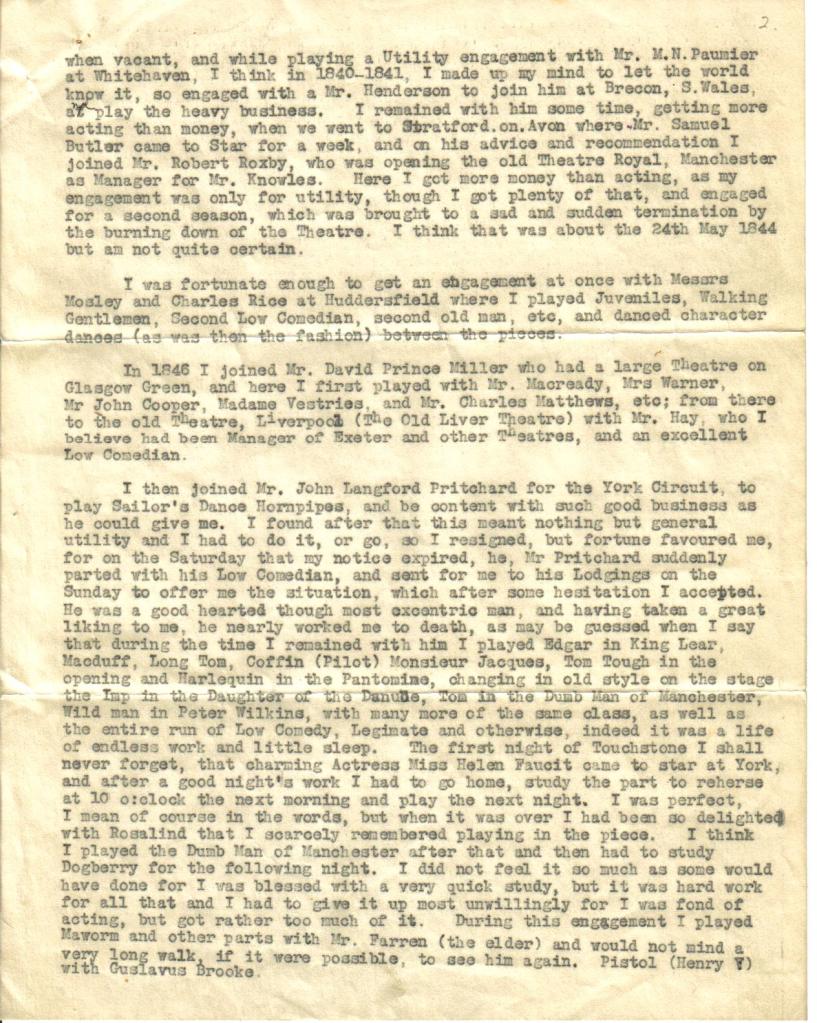

A2. Autobiography

In 1898 Lewis revealed that he was working on an autobiography:

“Mr Ball has contrived with great good luck to escape the ordinary interviewer, for he is unwilling to relate off-hand what he is himself putting into permanent form as an autobiography. For some years he has been writing these reminiscences of his long life. He remembers Edmund Kean, and is brimful of stories about his personal association with Macready, Phelps, Buckstone, Charles Dillon, Mathews, Helen Faucit, Madame Vestris and all the celebrities of the early Victorian stage. ‘There will be no romancing in my book,’ he says; ‘it will be all fact, historically correct at any rate, whatever value may attach to it. It is proving a labour of love to me in the winter of my days, but it will not see print till I am gone.”[60]

Sadly it never saw print. This is as far as he reached:

Note: His first memory of performing on stage does seem to be mostly accurate although the press billing is for the theatre in Hexham rather than Morpeth. Miss F H Kelly had been performing the part at Covent Garden just before – hence the ‘starring’ visit. His mother was taking part in play but it was a ‘Miss Parks’ who was billed as the child (daughter of two of the lead roles). It could be that Lewis had taken the part one night if Miss Park was unwell.

A3. Obituary of Father-in-Law William Benson”

Newcastle Daily Chronicle 8 May 1869:

“Death Of An Old Stager. A face familiar for many years to the habitues of the Sunderland theatres passed to the silent land on Friday last. Mr William Benson died at the residence of his daughter, in London, on that day, after a short but severe illness. His reminiscences of Sunderland dated back to a time which few play-goers in Sunderland can remember, when owing to the disuse of the present theatre, the followers of Thespis had but a humble booth in which to illustrate the varying passions of mankind, though in that booth, the late Charles Kean first essayed to play Hamlet, a part in which he afterwards became famous. Many were the stories Mr Benson told, and happy the associations he had, of the men now most eminent in their professions, who were then getting their foot on the first round of the ladder. Mr Benson was with the elder Beverley, and knew Mr Roxby and Mr Robert as boys. For upward of half a century he was in service of the Beverley family, and the relations on each side was creditable to both – fidelity on the one side being rewarded by esteem and confidence on the other. Mr Benson was a man of strict integrity and estimable in all the relations of life. He leaves but one daughter, Mrs Lewis Ball, his only son having been lost at sea many years ago.”

A4. The Green Room incident

This is related in Lewis’s autobiography and in a fuller account in a letter he wrote to Scott Clement in 1899:

“For myself, I never had one unkind word from him (i.e. Phelps), though I am sure I more than once deserved it. I remember on one occasion being guilty of a fault which I am sure no other manager would have overlooked or forgiven. It was during the first run of ‘Henry the Fifth’ (I think in 1853), in which I played Fluellen, Mr. Henry Marston was speaking in the green-room about my father, who was an old friend of his, and I was so interested that when the call-boy—I think the late Edward Righton held the situation at the time—called me for my next scene, I did not notice him; and thinking I had not heard, he touched me on the arm, and said, ‘ You are called, Mr. Ball.’

“T thanked him and thought no more about it, but went up to my dressing-room and quietly filling a pipe was indulging in a smoke, for though it was strictly forbidden we did now and then indulge, Mr. George Bennett being, I think, the greatest offender. By-and-by I heard loud murmurs, a rushing of feet and calls of ‘Mr. Ball! Mr. Ball.’ Then the prompter rushed into the room, exclaiming, ‘Mr. Ball, they are waiting for you and have been for some minutes, and Mr. Phelps on the stage all the time.’

“I can’t say I flew, but I do think I jumped down the stairs, and rushed on at the first entrance I came to—of course it was the wrong one. I was so confused that I made a sad bungle of the whole scene; and, when I left the stage, felt so disgusted with myself that I did not know if it would be best to run away and hide myself, or stay till he came off and get it over at once.

“T decided on the latter, and sat in the green-room waiting for him. When he came in he looked anything but pleased, and said, ‘Well, you made a nice thing of that! What excuse have you to offer?’ I gasped out, ‘None at all, Mr. Phelps. I am totally defenceless and have no excuse to offer; it was an act of gross carelessness. I can only express my great regret and sincere apology.’

“He then looked almost as much confused as I was, and asked, ‘Were you called?’ I said, ‘Yes, and thinking I had not heard him Teddy called me a second time.’ This confession appeared to amuse him, for, with a smile passing over his face, he said, ‘Well, you are the first actor I ever met who, having kept the stage waiting, did not blame the call-boy.’ And there the matter ended.

A5. The Kean Coincidence

In his autobiography Lewis had confided his desire in his youth to be a tragedian who might take on the mantle of Edmund Kean.

In 1802 a young Edmund Kean, possibly the finest Shakespearean actor of his time, performed in Teignmouth for a few nights at a small theatre in what is now Station Road. A small granite plaque marks that location. Such was his acting prowess that he was summoned by George III for a Command performance at Windsor. He died on stage in 1833 in the arms of his son Charles when he was performing Othello with his son as Iago.

Charles too became a noted Shakespearean actor and also managed his own company at the Princess Theatre, London. In 1853 he too was requested to stage a series of Command performances at Windsor together with the Sadler’s Wells Theatre. It was after the performance of Henry V that Queen Victoria singled out one actor in particular for commendation – Lewis Ball for his part as Fluellin. She reputedly said in a congratulatory message that she was “especially delighted with the ‘Welshman’ and wished the gentleman who played the part to know it”.

In the twilight of Lewis Ball’s career in 1895 this little story comes full circle. The theatre historian and playwright T. Edgar Pemberton had written a play about the life of Edward Kean (adapted from an original French version written in 1836 by Alexandre Dumas). The play had been specially written for the Edward Compton company[61]. Lewis Ball performed in the first ever production at the Royal Theatre, West Hartlepool taking the part of the old actor Tabberer, Edmund Kean’s faithful friend, who had been “elevated to the position of prompter in Drury Lane Theatre through the hero’s influence and who in the sequel so richly repays his benefactor’s kindness.”[62] He continued in that role as the play was taken around the country over the next couple of years. It is recorded that “….. as Tabberer Mr Lewis Ball could not be surpassed. His impersonation of Kean’s faithful friend was a splendid effort, finished in every detail”[63]

So, Lewis may not have reached the heights he once dreamed of in aspiring to surpass Edmund Kean but perhaps he took solace in being his faithful friend in a virtual life,

SOURCES AND REFERENCES

Specific extracts from contemporary newspapers are referenced below and are derived from British Newspaper Archives.

Ancestry.com for genealogy

Other sources, with hyperlinks as appropriate, are as follows:

Hull History Centre: – photo of Theatre Royal

Art Institute Chicago – picture of Ira Aldridge, the Captive Slave (CC0 Public Domain Designation}

English Heritage – picture of Gainsborough Theatre – An engraving of the Old Hall from the south, facing the courtyard, based on a 1793 drawing by John Claude Nattes. The theatre stair (left) led to the gallery level on the west side of the great hall.

British History Online – picture of Sadler’s Wells 1854 drawn by George Cruikshank

British Museum – picture of Fanny Ternan & Lewis Ball in All’s Well that Ends Well (Creative Commons Licence)

[1] Greenock Telegraph Wednesday 15 February 1905

[2] Dublin Evening Mail Wednesday 15 February 1905

[3] Birmingham Daily Gazette Wednesday 22 February 1905

[4] Manchester Courier Friday 17 February 1905

[5] The Era Saturday 15 June 1901

[6] Westminster Gazette Friday 11 March 1898

[7] Lloyds Weekly Newspaper Sunday 4 May 1902 (Note: Thalia was a Greek goddess, the Muse of Comedy and bucolic poetry.)

[8] Five page autobiography supplied by Johann Cotter. See Appendix for full transcript.

[9] Wikipedia

[10] The autobiographical reference is at odds with versions in the Press published in his obituaries. See Appendix for an explanation about the confusion.

[11] Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper 4 May 1902

[12] Autobiography

[13] Lincolnshire Chronicle Friday 9 May 1845

[14] The Era Sunday 19 December 1847

[15] Encyclopedia Britannica

[16] The Era Sunday 16 January 1848

[17] Yorkshire Gazette Saturday 29 July 1848

[18] Hull Packet Friday 4 August 1848

[19] Hull Packet Friday 29 December 1848

[20] Hull Advertiser 12 January 1849

[21] Yorkshire Gazette 24 March 1849

[22] Coventry Herald – 15 February 1850

[23] Leeds Intelligencer – 8 November 1851

[24] Hull Daily News Saturday 14 February 1852

[25] “Samuel Phelps and Sadler’s Wells Theatre”. https://digitalcollections.wesleyan.edu/object/wuptheatre-16

[26] Morning Advertiser Thursday 2 September 1852

[27] Morning Chronicle 26 October 1852

[28] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 15 February 1905

[29] Gateshead Observer 6 May 1854

[30] Illustrated London News 9 September 1854

[31] Illustrated Times 24 November 1855

[32] The Era 16 November 1856

[33] The Era 7 September 1856

[34] Bell’s Weekly Messenger 12 June 1858

[35] Morning Chronicle 29 June 1858

[36] The Drama of Yesterday and Today, Scott Clement, p198

[37] Scarborough Mercury 24 October 1863

[38] Newcastle Daily Chronicle – 8 May 1869 (See Appendix xx)

[39] The Era 12 December 1880

[40] The Era 26 February 1881

[41] The Era 13 February 1886

[42] Stratford-upon Avon Herald 22 April 1881

[43] The Stage 15 January 1886

[44] The Stage 10 September 1886

[45] The Scotsman 18 February 1891

[46] Irish Society (Dublin) 29 August 1891

[47] Liverpool Echo 19 March 1898

[48] Dublin Evening Telegraph 3 May 1898

[49] Belfast News Letter 5 May 1898

[50] Leeds Daily News 31 March 1898

[51] The Stage 2 June 1898

[52] Bradford Daily Telegraph 25 May 1898

[53] Dublin Evening Telegraph 7 May 1898

[54] Daily Telegraph & Courier 1905-02-16 – obituary

[55] Greenock Telegraph 1905-02-21 –obituary

[56] Teignmouth Post and Gazette 17 February 1905 – obituary

[57] Teignmouth Post and Gazette 24 February 1905

[58] Islington Gazette 5 May 1871

[59] Manchester Courier 1827-02-24

[60] Westminster Gazette 11 March 1898

[61] Birmingham Post 1895-01-04

[62] The Scotsman 1896-02-17

[63] South Eastern Advertiser 1 January 1898