Introduction – a Pre-Raphaelite Inferno

In my previous post I mentioned the wonderful names of various Victorians. Here is another one to conjure with – Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Yes, one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood; and, No, he’s not buried in Teignmouth cemetery. But there is a strong connection.

History is fascinating for its weave of time-lines connecting people, places and things. Because of that interconnectivity I could have chosen a number of starting points for today’s post but have selected Rossetti, or more specifically one of his drawings – Rupes Topseia.

This was a pen and brown ink caricature, or cartoon, which he is believed to have been produced in July 1869. I wonder if he borrowed the idea from his namesake’s, Dante Alighieri, famous work Inferno? The drawing depicts William Morris falling from a precipice into hell being watched from the ruins above by his business partners, including one Peter Paul Marshall, the subject of this blog.

Peter Paul Marshall had an interesting struggle in life – the pragmatism of having to earn a living versus the pull of his soul – his real interest in art. As we’ll see I believe that he tried to balance the two but was forever treading a tightrope.

There is a good article by Keith E Gibeling in the journal of the William Morris Society, Autumn 1996, – The Forgotten Member of the Morris Firm. The basis for the article is that “we know much about Morris, some about Faulkner but very little about Marshall” in the partnership of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. It explores the question of who this elusive partner in the firm was.

I shall draw on this but I want to go back to original sources where possible, starting with obituaries of the time which suggest that Peter Paul Marshall was more well-known during his lifetime than now.

The Early Years

I will start with the rather terse obituary published in the Western Times of 23 February 1900:

“The death is announced, at Teignmouth, of Mr Peter Paul Marshall, for many years City Engineer at Norwich. His chief works there were the fine new Foundry Bridge, the Isolation Hospital, and the opening up of the far-famed Mousehold Heath – the glory of Norwich. He leaves a widow and five sons, one of them, Mr J. Miller Marshall, a well-known local artist.”

It is interesting that the focus is on his engineering rather than his connection with William Morris or his artistic prowess.

The Eastern Evening News of 19 February 1900 starts to tell us a little more about his early life (bracketed information is from other sources):

“The deceased gentleman was born (in 1830) at Edinburgh and educated at the famous High School there. Having served in articles to the city architect of Edinburgh, he sought to advance his knowledge of engineering by joining Mr. (Thomas) Grainger, a famous C.E. in his day. In that capacity (as a draughtsman) he made preliminary surveys of various railway lines, and it fell to his lot to draw out all the working and detail drawings for the stations, goods sheds, and engine-houses of the Edinburgh and Northern Railway, including the Edinburgh Central Station. He went next (in 1847) into the office of Mr. James Newlands, an Edinburgh architect, and when that gentleman became borough surveyor of Liverpool he took Mr. Marshall with him as an assistant. In the capacity of assistant to the engineer of Liverpool Water Works he drew out all the plans and working drawings for the Park Hill, Everton and High Level Reservoirs, works which he personally superintended and completed. By appointment from the Liverpool Corporation he took up and completed the contract for the Rivington reservoirs and filter beds, the contractor for which had broken down.”

So a picture is emerging of Peter Paul Marshall as a serious engineer but also one who evidently had a keen eye for the detailed drawings required for that profession. In fact it seems that his father was a local artist and you have to wonder whether naming his son ‘Peter Paul’ was sheer coincidence or perhaps reflected an aspiration for him in the field of art. The same Eastern Evening News commented that:

“As a young man he studied art industriously at Edinburgh”, and,

“We would not be understood to point to Mr. Marshall as an artist of high and conspicuous powers, but we may fairly say that he possessed abilities which might have developed to remarkable purpose had destiny called him to the pursuit of art rather than of engineering”; and,

“If Mr. Marshall had not been an engineer he would conceivably have made an artist of some eminence”.

This was already evident by the time he reached Liverpool where he apparently exhibited paintings in 1852 and 1854 at the Liverpool Academy.

I wonder if it was at Liverpool that he first felt the real tension between his dual interests of engineering and art. Certainly, just as we saw in my last post about Admiral Rumbelow Pearse, this could be another example of historic serendipity – Peter Paul Marshall being in the right place at the right time.

Why? It could all be down to one man who was also in Liverpool at that time – John Miller.

Miller was Scottish-born too and also moved to Liverpool but in the early 19th century. In 1822 he had married Margaret Muirhead, daughter of a Falkirk merchant. Liverpool’s economy was expanding rapidly and Miller saw the opportunity to make his fortune through trading. With his newly acquired wealth he started collecting art and, by the 1850s, had developed a keen interest in Pre-Raphaelite art which he not only collected himself but also supported and promoted the movement.

Four years ago (2016) there was a major exhibition of Pre-Raphaelite art at the Walker Gallery in Liverpool. As the Guardian reported at the time:

“They were the punk rockers of their day – subversive, rule-breaking, dangerous – and a new exhibition argues that it was Liverpool more than any city outside London that made the pre-Raphaelites into Britain’s first modern art movement …… The central importance of Liverpool to a brotherhood of artists who, in the 19th century, changed the course of British art is set out for the first time at the Walker art gallery …… ‘We are saying that Liverpool was a hugely significant place for the pre-Raphaelites,’ said the curator Christopher Newall. ‘There was a tradition of art collecting that led to great things … but more than that there was a freedom of spirit, an intellectualism, a non-conformism and self-confidence that allowed this style of art to prosper, …… The exhibition argues that Liverpool’s art scene rivalled London’s. When the early pre-Raphaelites were being treated with contempt by the Royal Academy in London, they were welcomed with open arms by the Liverpool Academy keen to exhibit the new and the daring. And when they struggled to sell their paintings, they found rich and willing patrons in Liverpool.”

So, given the lively artistic ambience of Liverpool, it’s hardly surprising that Peter Paul Marshall’s path crossed with that of John Miller. But this crossing was much deeper – Peter Paul married Miller’s youngest daughter, Augusta (“Gussy”) Buchanan Miller in March 1857, although by this time he was living in Bloomsbury Square, London.

The London Whirl

What brought about Marshall’s move from Liverpool to London is unclear. Later in 1857 he was appointed as surveyor to the Tottenham Board of Health, but had he left his position in Liverpool long before that and come to London jobless? If so, had he been driven by his artistic desires – perhaps drawn by the attraction of being closer to the centre of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and with the contacts of his father-in-law? Was engineering then his fall-back and the certainty of a regular salary, especially now that he was married?

With marriage came children and, by the time of the 1861 census, he and Augusta had two sons – William (age 3) and James (age 2). He was being kept busy professionally – his duties included the maintenance of roads and footpaths, the inspection of dilapidated houses, and the improvement and upkeep of water supply and sewage facilities. In 1860 he had also joined Tottenham’s 33rd Middlesex Rifle Volunteers which was part of a national response to the possibility of a French invasion. Wearing his professional hat he was able to supervise the construction of the firing range and various other buildings for the company. His obvious enthusiasm was marked by a little verse by a Sally Gunn and collected in the article by Keith Gibeling:

I think I never saw. though perhaps I may be partial.

A more milingtary (sic) looking man than our surveyor, Mr. Marshall,

And very martial. likewise, we all thought that he appear’d

With that darling pair of whiskers, and that lovely flowing beard

He was also still pursuing his own artistic interests. Here are a few examples I have found from this period:

Haymaking is a picture of Marshall’s sons William and Johnnie with their mother and the children of the late J H Stewart. It’s set in the hayfield at the back of their house in Tottenham with Epping Forest in the distance. It had been exhibited at the Royal Academy.

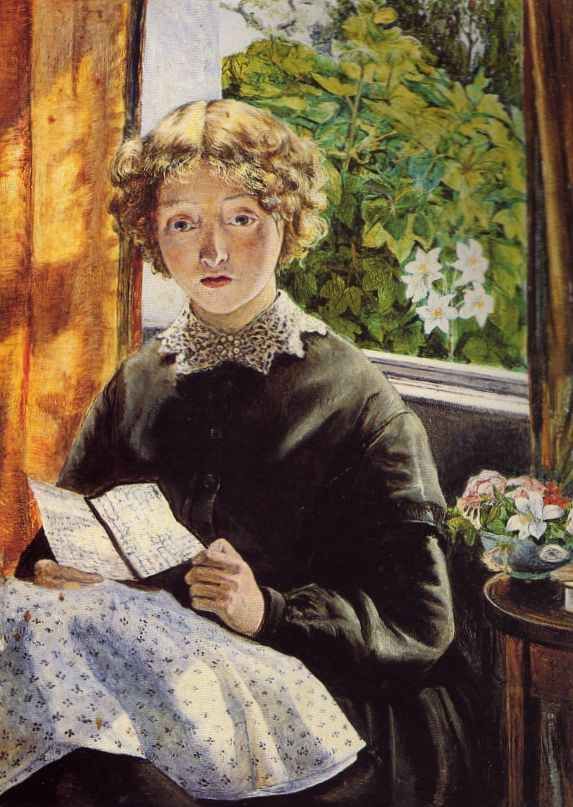

A Letter from Home. It is thought the sitter was a Governess and the black edges to the letter suggest a death. Marshall painted in the window irises, a symbol of death.

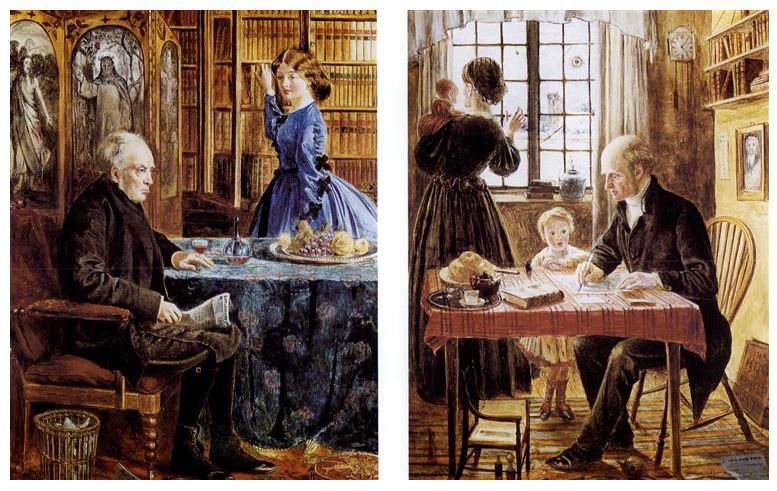

A Clerical Life. This was created as a pair of paintings – The Rich Cleric and his Wife ; and The Labourer is Worthy of his Bread. The original bore a label ‘8 Red Lion Square’ which was the address of William Morris’ workshop between 1861-5.

The Fifeshire Journal of 26 March 1863 commented on one of Marshall’s paintings on display at an exhibition of the Royal Academy:

“On Monday evening the hospitable doors of the Royal Academy of Pictures opened to a numerous but not equally select assemblage of ticket-holders, invited to a conversazione in the galleries of paintings ……. A very striking picture, by Peter Paul Marshall, entitled ‘First Thoughts of the Locomotive’ catches the eye at the first visit. It represents the great engineer modelling an engine in clay by the light of the boiler fire, which throws a lurid glare, half natural, half fantastic, over him – his wife by his side, and his favourite rabbits at his feet. The proud, solicitous look of his wife, as she watches his work with interest, is most happily expressed, as is his own thoughtful, reflecting face; and a plate and sandwich on the ground beside him are done with pre-Raphaelite accuracy.”

I wonder if this is a refrain back to his civil engineering days in Liverpool.

At the same time that all of this was going on it seems that Marshall was also busy in the social whirl that was the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (“PRB”). This is reflected by a few snippets from the Wife of Rossetti, Her Life and Death by Violet Sutton. The first of these shows the breadth of society caught up in this whirl of social events at the home of Dante Gabriel Rossetti:

“For they were entertaining tremendously. Invitations, lively and informal, ran, ‘Come, we have hung up our Japanese brooms, etc.’ Contesses rolled in their carriages to Blackfriars to see the Pre-Raphaelites in their habitat – the Ladies Waterford, and Trevelyan, and Bath, all eager to break new ground and meet the exponents of the cult they admired and whose pictures they bought. A good sprinkling of Philistines like Hardman and Anderson Rose; journalists like Hepworth Dixon and Joseph Knight; among authors, Westland Marston and his daughters. Patmore and a wife, Meredith with his handsome head, Edward Lear, round and funny; Martineau, Halliday, chattering Tebbs and Mrs. Tebbs who was their dead friend Seddon’s beautiful sister. There would be Sandys, Mark Anthony and his daughters; Peter Paul Marshall and his wife Gussy, the daughter of jolly old John Miller of Liverpool, the picture buyer; ‘Val’ with a head like a broom and the heart of a —— (vide Rossetti’s limerick), and Inchbold, a dangerous guest because he always wanted a bed and never went away; Hungerford Pollen, Munro, Hughes and Faulkner and a couple of Christina’s admirers, Cayley and John Brett (‘No thank you, John’). There would be Morris and his wife, of course, and the Joneses. Not Stephens; not asked, he had just married Mrs. Charles and had said Lizzy was ‘freckled’. Holman Hunt was away. Excepting Georgy there were not many of Lizzy’s particular friends. Emma Brown was at the sea and Bessie Parkes and Barbara Bodichon were abroad. But Mary Howitt brought her shy husband, Alaric ‘Attila’ Watts, and sat with him in a corner taking notes for her diary that would have rejoiced a daily paper of to-day.” (p. 272)

Then there were smaller gatherings:

“In the evenings ‘Poll’ Marshall, accompanied by his Gussy, would sing ‘Clerk Saunders’ to please Mrs Rossetti and ‘Busk ye, busk ye my Bonnie Bride’ for Mrs. Ned, and she would sing in her high wild voice ‘La Fille du Roi’ out of ‘Echos du Temps Passee’, to please Ned and Top. The world had grown older. Gabriel was thirty-three.” (p 283)

And other things they did together:

“Gabriel had to go without her to the christening of little Jane Alice Morris in the last days of January. He went down with some of the fellows, Marshall, Brown and Swinburne, who was just back from the continent and had not yet called on Lizzy. Janey was going to put them all up somehow, in the fearless old Pre-Raphaelite fashion. The Joneses were already there – Georgy to help the delicate Janey in preparing for such a large party. It was given to show the new house and the new baby to as many of the old PRB as could be got together and to the members of the new firm which had been constituted, as it were, on its ashes, to fight Mr. Perkins’ aniline dyes and nurse the silk trade, nearly killed by Cobden’s Bill of three years ago, since when no lady’s gown had been able to ‘stand alone. Premises had been acquired in Queen’s Square.

Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co

So we have now reached another significant point in Peter Paul Marshall’s life. He was still working full time as the surveyor in Tottenham but had now committed to business with William Morris. As Violet Sutton noted:

“The firm, founded in 1860, consisted actually, like the P.R.B., of seven – Rossetti, Morris, Brown, Jones, Faulkner, Philip Webb and Peter Paul Marshall. Faulkner wrote to William concerning the first and only prospectus issued of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., 8 Red Lion Square, Holborn. Fine Art Workmen in painting, carving, Furniture and the Metals. ‘A very desirable thing,’ Scotus says, who had not been asked to be a member – and he did so like his fingers in every pie – ‘a very desirable thing, Fine Art Workmen! But isn’t the list of partner a tremendous lark!’”

William Morris’s life and works are well documented and exemplified through the William Morris Society, the William Morris Gallery, organisations such as the National Trust and the Victoria and Albert Museum, and numerous biographical works. So there’s little to be gained by repeating that here. Rather I want to focus on Peter Paul Marshall’s role in this enterprise.

According to William Michael Rossetti it was Peter Paul Marshall who came up with the idea for the Firm originally which could explain why his name appeared in the title to the business even though he was not as active as an artistic contributor. In the early years I imagine there would have been a burgeoning of energy and enthusiasm as the business got off the ground and Marshall certainly contributed artwork during this period which survives today.

One of the product lines of the Firm was stained glass which, judging by the number of installations, was potentially a fairly lucrative market and, of course, would have given the Firm some visibility. The Firm won a medal for their stained glass work in the International Exhibition of 1862 and, as Aymer Vallance comments in his 1897 work William Morris, His Art, Writings and Public Life:

“Ext No. 6734: Stained glass windows. The report of the juries and list of awards witnesses that a medal (United Kingdom) was bestowed on the firm for their work ….. the award was given for artistic qualities of colour and design ….. At least one expert, Mr Clayton … pronounced the work of Messrs. Morris and Co. to be the finest of its kind in the Exhibition. Before the close of the Exhibition orders were received through Mr. Bodley, then a generous friend and supporter of the firm, for glass for St. Michael’s, Brighton.”

St. Michael’s marked its 150th anniversary in 2012 with a project for the renovation of its Great West Window – “one of the finest achievements of Pre-Raphaelite glass making, and one of the most important stained glass windows of the 19th Century.” One of the designs, St Michael and the Dragon, is attributed to Peter Paul Marshall.

Victoria and Albert Collections. Original Design by Peter Paul Marshall

St Michael and The Dragon – The Window

Other examples of stained glass design contributed by Peter Paul Marshall include:

The “Military Window” at St Martin’s Church, Scarborough. According to the church “it is one of the earliest windows produced by Morris and Company, and was installed in 1862 in memory of a Major Monnins who died in 1860. The windows by Marshall are two of the few he executed for The Firm.” The two panels attributed to Marshal are Joshua and St. Michael the Archangel.

The Joshua Window

St Michael The Archangel

East Window of Bradford Parish Church, 1863. As the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society explains: “The theme of the window might be described as ‘Witnesses to Christ’ ….. The venerable figure of the patron saint, Peter, designed by Peter Paul Marshall, occupies the lower part of the central panel. His green cloak discloses a white robe, and from a golden chain round his neck hang two not very traditional keys and a bible.”

In the next few years the Firm blossomed. As the Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser of 27 October 1897 commented on Vallance’s book:

“The history of this firm makes the most interesting chapter in the work, and becomes an astonishing record of the genius and miraculous powers of work of the dominant partner.”

However, it is also clear that all was not well with the running of the business ….. which brings us full circle to where we started this story with Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s cartoon Rupes Topseia.

As I said earlier, the cartoon depicted William Morris falling into hell from a precipice whilst being watched by his business partners. There has been much debate about the meaning of the cartoon, published as it was in 1869, but it clearly foresaw the demise of the Firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.

The front-runner theory is that the cartoon refers to Warrington Taylor’s criticism of Morris’s extravagance and incompetent management which could soon throw the Firm into bankruptcy (Warrington Taylor was the business manager of the company from 1865 until his death in 1870). Whatever the interpretation, Marshall’s future was now set to change though it was another five years before the separation from Morris as the London Gazette of 6 April 1875 reported:

“Notice is hereby given that the Partnership heretofore subsisting between us the undersigned, Ford Madox Brown, Charles Joseph Faulkner, Edward Burne Jones, Peter Paul Marshall, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Philip Webb, and William Morris, trading as Morris, Marshall, Faulkner, and CO., and Morris and Co., as Fine Art Workmen in painting, carving, Stained Glass, Furniture, and the Metals, at No. 26, Queens-square, Bloomsbury, in the county of Middlesex, has been dissolved by mutual consent; and that the said business will henceforth be carried on solely by the said William Morris, to whom all debts due to the late firm are to be paid and by whom all claims against the said late firm will be discharged – Dated this 31st day of March, 1875.”

Marshall received £1000 for his share of the partnership – equivalent to about £116,000 today. He would need this.

Goodbye to London and All That.

By this time he had six children to support – William Miller, James Miller, Lancelot Paul, Pauline, Patrick Hugh and Geoffrey; and two years earlier he had resigned from his surveyor’s post in Tottenham following a serious outbreak of typhoid there.

According to Gibeling he was more or less unfairly forced out of his post:

“The loss of his job at Tottenham, it must be kept in mind, was due more to village politics than it was to any lack of ability. In fact, Marshall’s later years at Tottenham actually saw him in the vanguard of sewage treatment. He encouraged experiments in sewage treatment techniques by allowing other engineers and scientists to perform tests at the Tottenham sewage works. Marshal! was an engineer in the golden age of engineers, a man who pitted himself against the insidious problems that had plagued and frustrated city-dwellers for centuries. Men like Marshall were the heroes of what Asa Briggs has termed the ‘Age of Improvement’”.

Whatever the reasons behind his resignation this must have been a devastating period in his life as his secured income came to an end and his aspirations in the art world were suddenly curtailed. I wonder how he felt about this double loss.

It appears that it was four years before he was able to secure another position. He applied immediately in 1873 for the position of Borough Surveyor and Engineer for Leeds but was unsuccessful. He was eventually appointed In 1877 as City Engineer and Road Surveyor for Norwich and finally left London life and his Pre-Raphaelite aspirations behind. Whether he maintained connections with the group is uncertain but for the next 16 years until his retirement in 1893 he applied himself with his customary professionalism to a range of engineering tasks in Norwich. His obituary notes:

“Amongst the principal works associated with his tenure of office may be mentioned the new Foundry Bridge, the Isolation Hospital, and the initiation of the new sewerage scheme. It was he also who laid out Mousehold Heath. In connection with the paving scheme he introduced the system of paving on sand, which has since been widely adopted in other places and by other engineers.”

He did continue his art as well and the obituary continues:

“.…. in his time exhibited at the Royal Academy and the British Institution, as well as in the humbler galleries of the Norwich Art Circle. In water-colour he was very successful, and many of his sketches are treasured in local salons in company with those by his artist son, Mr J Miller Marshall.”

Retirement

Interestingly his son may have surpassed him in artistic ability. When Peter Paul Marshall retired he and his remaining family moved down to Teignmouth and the Norfolk News of 10 March 1894 commented:

“No less an authority on art matters than Mr. William Morris says, ‘The duty of the art missionary should be to induce the public to use its eyes, and to learn to appreciate the beautiful in nature.’….. Local art cannot but be the poorer by the removal from amongst us of Mr. J. Miller Marshall, and at art gatherings his clever and genial father will also be greatly missed. Mr. P. P. Marshall – though not so well known in his art capacity as his son – was a splendid draughtsman, and a great favourite with the members of the art circle. This was especially the case with the ladies; more than one of whom I have heard speak of him as ‘dear man’”.

The move to Teignmouth also prompted both Marshalls, father and son, to part company with most of their artwork. As the Norwich Mercury of 6 December 1893 reported:

“EXHIBITION AT THE ART CIRCLE ROOMS, NORWICH. During the last few days the opportunity has been afforded the public of inspecting a somewhat large collection of local paintings, the work of two artists in the city, whose names will be familiar to very many, Mr. P. P. Marshall and Mr. J. Miller Marshall. The former, perhaps, is better known to the citizens as their late City Engineer, and it will, doubtless, come as a surprise to them to know that the gentleman in question is, in his particular line, an artist with abilities of a very high order. His son, Mr. J. Miller Marshall, has long been a great favourite at the local exhibitions, and, as with his father, so his success has not been confined to local displays, contributions of his having at various times found places on the walls of the Royal Academy. These two artists are shortly leaving Norwich for the south of England, and hence the disposal of the contents of their studios. By permission of the Norwich Art Circle, the display is made in their three rooms in Queen Street, a private view being given on Saturday, followed by free admission to the general public till tomorrow (Wednesday). More than 150 works of the two artists are catalogued, and of these a very large number – the majority indeed – are by Mr. P. P. Marshall. Many of his contributions – more especially those of his younger painting days – show a freshness and vigour of style which, with the developing influence of after years, might have brought out work of a very high order indeed. Almost the first thought in the visitors , when making the tour of the exhibition, must have been that here, in these early efforts was the promise of a great artist; but to engineering Mr. Marshall’s energies were given, and art, although it did not altogether lose its devotee, was the poorer for the loss of work which would undoubtedly have brought with it distinction. His best efforts are seen in portraiture. Some of the more striking of Mr. Miller Marshall’s works depict well-known Broad scenery, but though these will perhaps attract a large share of public attention, he has also a deal of other noteworthy work – quaint bits of architecture in and around the city and county. The exhibition, on the whole, is very well worth a visit by any one at all interested in the work of our local artists.

Art remained an interest for Peter Paul Marshall during his time in Teignmouth and it appears he might still have done commissions. The Eastern Evening News of 19 February 1900 mentions:

“As showing that Mr Marshall’s artistic tendencies remained with him in his years of retirement, it may be mentioned that since he went to live at Teignmouth he designed a window for a church at Havre, the erection of it being carried out by an Exeter firm.”

Peter Paul Marshall died on 16 February 1900. He had apparently been in good health upto five months earlier but then, as the Norwich Mercury of 21 February 1900 reported:

“.…. a malady affecting one of his legs began to show itself. But for his age amputation would have been resorted to. He sank gradually under the progress of the disease, and death overtook him on Friday evening”

He left a wife and five sons but also, as we have seen, a legacy in both the engineering and art worlds. I wonder if he was content with that legacy though. Unlike his pre-Raphaelite contemporaries he had not come from a wealthy background. Maybe if he had, he would have had the opportunity to pursue his undoubted artistic talents and be seen today on the same footing as Morris and Rossetti. We shall never know.

He is buried in a simple grave, plot U58, not so easy to reach now, lying as it does beneath a large weeping lime. The gravestone is weathered and virtually illegible. It originally carried, as an epitaph, the refrain from an early nineteenth century Scottish poem and ballad by Lady Carolina Nairne:

The day is aye fair

In the land o’ the leal.

And that’s Peter Paul Marshall. For a few loose ends to the story see the section after the references.

Sources and References

Extracts from contemporary newspapers are referenced directly in the text. Other sources, with hyperlinks as appropriate, are as follows. For further information and queries which have turned up during this research check out the “Loose Ends” section after these references.

GENERAL

Ancestry.com for genealogy

British Newspaper Archives for all snippets from contemporary newspapers

Wikipedia for general background information

SPECIFIC

Arts & Crafts Living: – a short biography

The Art of William Morris, Aymer Vallance, 1897, George Bell & Son

Friends of St Michaels Church, Brighton: – 150th Anniversary and Windows

Friends of St Martin’s Church, Scarborough: – Windows

Victoria & Albert Museum: – Image of St Michael and the Dragon

Bradford Historical Society: – Bradford Cathedral windows

Bradford Cathedral: – Lady Chapel windows

BRANCH: Britain, Representation, and Nineteenth-Century History – comments on Morris:

Arcadia auctions: – source of various Marshall paintings

William Morris: Design and Enterprise in Victorian Britain, Charles Harvey, Jon Press, 1991

The Wife of Rossetti, Her Life and Death. Violet Hunt. Dutton & Co, New York, 1932

The Rossetti Archive: – Rupes Topseia

Pre-Raphaelites: Beauty and Rebellion. Christopher Newall, Ann Bukantas. Oxford University Press. 2016

National Portrait Gallery: – Rupes Topseia

William Morris Society: – various references

Arts Docbox – William Morris, an Annotated Bibliography:

Victorian Poetry, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Fall, 1999), pp. 353-429 (77 pages), Published by: West Virginia University Press

Liverpool Museums: – comments on John Miller etc

Rampant Scotland – Selection of Scottish Poetry (Land of the leal)

Peter Paul Marshall: The Forgotten Member of the Morris Firm, Keith E. Gibeling, 1996

Michelle Heseltine – photo of St Peter Window, Bradford Cathedral

Peter Paul Marshall – Loose Ends

Family

Peter Paul Marshall was survived by his wife and five sons. Augusta may have died in 1915 in Williton, Somerset and their daughter, Pauline, may have died in 1899 and have been buried in the West of London and Westminster Cemetery, Old Brompton. The sons had followed a variety of careers, though all with links to their father’s past. According to the obituary in the Norwich Mercury, these were:

- Mr W J Marshall, a marine engineer in the service of the Chilean government

- Mr J Millar Marshall, an artist well known in Norfolk

- Mr L P Marshall, one of the staff in the office of the City Engineer in Norwich

- Mr P H Marshall, a member of the firm MacVicar, Marshall & Co, shipping agents of Liverpool

- Mr G Marshall, a mining engineer, who returned to this country from Johannesburg on the outbreak of the war

Of these, James Millar Marshall had picked up the artistic baton as we have seen. There is an excellent article by Ross Bowden describing his travels around Australia in 1892/93 – “James Miller Marshall: a Norwich School painter in late 19th-century Australia”.

He was depicted in 1938 as the artist ‘Bradley Mudgett’ in Norman Lindsay’s book Age of Consent. Norman writes that the artist’s appearance made such an impression on him that he used him as the model, visually speaking, for the artist–hero, Bradley Mudgett. When that book was filmed in 1969, the English actors James Mason played the artist and Helen Mirren the love interest.

There are a number of mentions of James in the local Devon press since he was an active participant in the art scene here. Here’s one from the Express & Echo of 12 September 1899:

“ ART EXHIBITION AT ELAND’S GALLERY: J Millar Marshall is represented by some attractive pictures from the neighbourhood of Teignmouth the best of which (109) is ‘A View of Teignmouth from the Old Quay’”

And here is an example of one of his works – a Harbour Scene – which looks rather Turner-esque.

Finally ….. Some Poetry

Limerick, Dante Gabriel Rossetti

For those interested in “Val” …..

There is a big artist named Val,

The roughs’ and the prize-fighters’ pal:

The mind of a groom

And the head of a broom

Were Nature’s endowments to Val.

Land o’ the Leal, Lady Carolina Nairne

I’m wearin’ awa’, John

Like snaw-wreaths in thaw, John,

I’m wearin’ awa’

To the land o’ the leal.

There ‘s nae sorrow there, John,

There ‘s neither cauld nor care, John,

The day is aye fair

In the land o’ the leal.

Great research and write up re PP Marshall….thanks Neil👍🏻

________________________________

LikeLike