As you come out of Teignmouth on the Dawlish road and approach the top of the hill, keep an eye out on the left-hand side and you may catch a glimpse of one of Teignmouth’s hidden gems of architectural and historic interest. St Scholastica’s Abbey nestles behind the pallisade of tall trees. It is now surrounded to the west by a housing estate and itself was converted to residential accommodation some 30 years ago.

The immediate questions are: How did it get here? Why? And who brought it about? Given this blog the answer to the last question is probably obvious – the Countess Isabella Jane English. But her contribution lies in the context of the answers to the first two questions. To answer those we need to follow several strands that converge over time on the Countess English.

For the first of those strands we go back some 1500 years.

Soar to Heaven like a Dove in Flight

This is where history and legend do battle. What follows comes from the “Dialogues of Gregory the Great”. These are written along the lines of a story and have little contemporary documentation to validate them. So in time-honoured tradition, where authenticity may be challenged, I will start with the caveat – Tradition has it that ……

In Nursia, in the Italian region of Umbria, in 480 AD a wealthy couple – Anicius Eupropius and his wife Claudia Abondiata Reguardati – had two children, Benedict and Scholastica who may have been fraternal twins.

Both were dedicated to God from a young age.

Benedict became the founder of the eponymous Benedictine order though only after an early life of:

- disillusionment with religious teaching in Rome (where he was disgusted by the paganism and immorality he encountered there);

- the deprivations of living in isolation as a hermit in a cave at Subiaco just east of Rome;

- surviving the challenge of lust;

- surviving also several assassination attempts;

- being credited with a number of miracles; and,

- establishing in 530AD the monastery of Monte Cassino.

More importantly though he wrote a “Rule” for his monks. Essentially this was a code for life that blended compassion and discipline in a way that influenced later monastic orders and is claimed to have shaped the future of Europe.

Meanwhile Scholastica pursued her own route to following God by living in a hermitage with other ‘consecrated virgins’ in a group of houses at the foot of Monte Cassino. This is now the site of an ancient church, the ‘Monastero di Santa Scholastica’.

In ‘De Laude Virginitatis’ the Anglo-Saxon bishop replays the story of how Scholastica and Benedict would meet up once a year and spend the day in worship and discussing sacred texts and religious issues. But one year something different happened. They had supper and continued their discussion until it was time for Benedict to leave. Scholastica though asked him to stay – the speculation is that she had a premonition that her death was near. Benedict insisted that he had to leave, at which point Scholastica closed her hands in prayer and a wild storm started. “What have you done?”, Benedict asked. Scholastica simply answered “I asked you and you would not listen, so I asked my God and he did listen. So now go off, if you can, leave me and return to your monastery”. Of course Benedict was unable to do that and they ended up talking all night.

Benedict and Scholastica in discussion

Three days later Benedict saw his sister’s soul leaving the earth and ascending to heaven in the form of a shining white dove. He had her buried in his monastery in a tomb he had already prepared for himself. She is reputed to have died on 10 February 543 AD, marked now as St Scholastica’s Day and the official date of her being made a saint. She is the patron saint of Benedictine nuns, education, ‘convulsive’ children and is invoked against storms and rain.

Benedict himself died of a fever a few years afterward ….. tradition has it on 21 March 547AD. He was buried with his sister.

And so the Benedictine Order was founded and gradually spread across Europe. Scholastica is traditionally regarded as the foundress of the Benedictine nuns and is remembered in a prayer:

“O God, to show us where innocence leads, you made the soul of your virgin Saint Scholastica soar to heaven like a dove in flight”

Nuns in Exile

For the next 1000 years monastic orders spread and flourished throughout Europe until the Catholic church encountered the challenge of the Reformation movement which rejected the doctrine of papal supremacy and eventually led to the break from Catholicism which became known as Protestantism.

In Britain though it appears that there was more to it than purely religious disagreement. Henry VIII needed income to finance his military activities and saw the monastic houses as an answer to his economic problems. It is estimated that the religious houses owned about a quarter of the nation’s landed wealth.

The Act of Supremacy gave Henry VIII the authority he needed for the dissolution of the monasteries and the seizure of their assets. According to Professor George W Bernard this was “one of the most revolutionary events in English history”. The move seems to have been cautiously popular – the view expressed by Erasmus was that monastery life was ‘lax, comfortably worldly and wasteful of scarce resources’ and that ‘the overwhelming majority of abbeys and priories were havens for idle drones; concerned only for their own existence, reserving for themselves an excessive share of the commonwealth’s religious assets, and contributing little or nothing to the spiritual needs of ordinary people.’ It sounds like Benedict’s Rule of ‘compassion and discipline’ had been long been forgotten, or at least that is what we may be led to believe.

Elizabeth I continued Henry’s work by forbidding all forms of Catholic religious life. The consequence of this was that Catholics wishing to pursue a religious life or gain a Catholic education had to go to the continent. Specific to this story this led to the establishment of 22 convents in Flanders and France to which around 4000 women from catholic families went into self-imposed exile between 1600 and 1800. One of those convents was the Benedictine convent of Dunkirk which was founded in 1662. The convent lasted there until 1793 when, yet again, another religious purge was to affect religious life. This time it was the French revolution.

According to the definitive book ‘A History of the Benedictine Nuns of Dunkirk’ it was Sunday October 13th 1793 when the cloister of the convent …..

“was filled with gendarmes, and the community were informed that their property was confiscated, and that they were to prepare to leave their convent in a few hours”, and

“our property sequestered, we were allowed to take our clothes, but such was the hurry and confusion that they did not give time nor carts sufficient to get them out of the house, so that many were obliged to come out with nothing but the clothes upon their backs.”

They were dispatched to Gravelines and imprisoned there for eighteen months in harsh conditions during which time eleven out of seventy-three nuns died. During this time they were also under constant psychological threat of the guillotine:

“It was the cruel device and pleasure of their heartless soldier-jailers to march these poor religious frequently to view the guillotine, whilst they knew not how soon they might themselves be the next victims. Their chance of escaping that terrible death was at one time slight indeed; for after the death of Robespierre it was discovered that he had done them the honour of inscribing all their names in his pocket-book.”

However, they continually pressed to be allowed to return to England and eventually, on 30th April 1795 they set sail from Calais and arrived three days later in London. There they were met by the Lady Abbess Prujean’s cousin, the Hon. Mrs Molyneux. As the book relates:

“The figures which our nuns presented were ludicrous in the extreme. They were clothed in garments of various shapes, texture and hue, bed curtains forming the principal feature in the material of which they were made. ‘No marvel was it that the servants smiled,’ Lady Abbess’s nephew remarked …..”

Five days later they were in their new establishment – three houses in Hammersmith which had been the former site of a convent before the reign of Henry VIII.

We are now approaching the involvement of the Countess English but, before that, one more character needs to be introduced in the story – Elizabeth Dalton.

The Dalton Legacy

A few miles to the south of Lancaster lies the parish of Thurnham which once formed part of the estate presided over by Thurnham Hall, the seat of the de Thurnham family who remained there until their line petered out in 1553. The Dalton family acquired the estate through Robert Dalton and were lords of the manor subsequently until 1861. There is reference to a Robert who had ten (maybe seven!) daughters who were staunch, pious Catholics, so much so that they were known as the “Catholic Virgins”. The family survived the impact of the dissolution of the monasteries and their involvement in the failed Jacobite uprising of 1715.

Elizabeth Dalton;

Lancaster City Museums

Eventually in 1837, with no more male heirs of the Dalton family, the estate passed to Elizabeth Dalton who was one of several sisters all of whom died before her without children. The estate was more than just the manor lands – there is evidence of extensive ownership of property in the Glasson Docks area. She is described as “a remarkable woman of stern will and great piety” and likened to those Dalton “catholic virgins” of two hundred years earlier.

In 1848 she contributed £1000 (equivalent to about £90,000 today) towards the completion of Thurnham Church, and in around 1859 another £1098 for the completion of the Lady Chapel in Lancaster Cathedral which contains the following memorial:

“Pray for the five sisters of the family of Dalton of Thurnham: Charlotte, deceased Feb. 28, an. 1802; Mary, Aug.17, 1820; Bridget, Aug. 5, 1821; Lucy, Nov. 14, 1843; and Elizabeth, Mch. 15, 1861. Elizabeth, the last of a race firm through troublesome times in their devotedness to the Catholic faith, which they sustained in this neighbourhood by their sufferings and influence, built and endowed this chapel of our Lady Immaculate to secure for herself and sisters the prayers of the faithful.”

I have not been able to find out much more about Elizabeth Dalton but there is one remaining piece in the jigsaw puzzle of this story which yet again is evidence of the serendipitous nature of history – being in the right place at the right time.

As a child Elizabeth was sent to be educated at Hengrave Hall, Suffolk. This had been used as a refuge by the English Augustinian Canonesses of Bruges who, as in the story of the Benedictines described earlier, had also fled in 1793. They were led by their Prioress Mother Mary More and, once settled, ran a school there. Also at the school at the same time was a young girl, Frances Huddleston, from another old and staunch Catholic family. She and Elizabeth became friends and it was that friendship which created the serendipitous connection that shaped the rest of this story.

The Countess English – Background

So finally the strands converge on the Countess Isabella Jane English. As Jean English notes in her article for the Bristol and Avon Family History Society:

“Isabella Jane English was born in Bath on the 5th February 1814 ….. Isabella came from a staunch Catholic family. Her father was John English, Solicitor and Alderman of Bath and her mother Frances was a Huddleston, and cousin to the Huddlestons of Sawston Hall, Cambridgeshire, where she had lived on her father’s death.”

She was the third of ten surviving children and was fortunate in having as her godmother Charlotte Georgiana, Lady Bedingfeld whose letters and journals are ‘a rich source for the study of Catholic spirituality, education and marriage in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, as well as being a valuable record for Norfolk history and women’s history.’ Lady Bedingfeld was also later ‘Woman of the Bedchamber’ to Queen Adelaide, wife of William IV.

Jean English’s narrative of Isabella continues:

“We have no record of her childhood but she emerges in 1835 as a young woman of twenty-one, when her mother ….. takes her to Thurnham Hall, Lancaster to meet her old school friend, Miss Elizabeth Dalton. She was so taken with Isabella that she asked if she could stay with her and act as hostess to her many visitors.

Incredibly this arrangement lasted twenty-six years, Isabella remaining her companion until Elizabeth died in 1861. She then inherited a fortune from Elizabeth’s estate. The estate was in two parts:- the ‘entailed’ estate was intended to follow a family line and included Thurnham Hall which all passed to a distant cousin, Sir James Fitzgerald; the remainder, including all those properties in the Glasson dock area, passed to Isabella.

A condition of the inheritance was that she should spend a large proportion on charity. She did this with alacrity, divesting herself of around £30,000 (worth £2.5 million today) within six months. Realisation of income from the estate continued through to at least 1867 when “a mass of property belonging to Miss IJ English was offered by auction, including the Victoria Hotel and 26 cottages at Glasson”.

Where did that £30,000 go?

This is where we come full circle to where this story started with St Scholastica’s Abbey.

The Countess English and St Scholastica’s Abbey

Let’s return to the book A History of the Benedictine Nuns of Dunkirk to explain what happened. We left the nuns in 1795 having just moved into premises in Hammersmith which they opened as a school the following year.

For the next 60 years or so the convent and school flourished and paths crossed. For example: Isabella’s godmother (Charlotte Georgiana Lady Bedingfeld) stayed there as a boarder in 1830 when her husband died and remained until her own death in 1854; Isabella’s sister, Dame Mary Thais English, joined in 1836 and contributed to the convent’s musical reputation, composing at least one Mass and a number of voluntaries; In 1860 Isabella’s brother, the Most Rev. Dr Ferdinand English, received the “pallium” at the convent as Archbishop of Port of Spain, Trinidad.

And so we pick up the story in 1861:

“Miss Isabella English came on June 16th, 1861, to visit her sister, together with their brother, the Very Rev. Louis English, Rector of the English College in Rome. She desired to devote part of the large fortune she had inherited to benefit some convent; at first she thought of helping some Franciscan nuns, but Dr English said ‘Why do you not assist your own sister’s community?’ She followed his suggestion, and it was by means of her generosity that a new home for our Sisters became a possibility.”

So the ball was set in motion for a move from Hammersmith, which had been mooted by Cardinal Wiseman as early as 1857 because of the falling number of pupils caused by the attraction of modern teaching orders with new methods of education. The story continues:

“Miss English mentioned at this visit that she had heard of an estate to be sold about seven miles from Bath, which, if it should prove suitable, she offered to purchase.”

In the words of Lady Abbess Selby:

“She wished me to go with Dame Mary Thais and herself to Bath to see if we liked the place. Accordingly, with leave from the Vicar-General, I was next morning metamorphosed into a fine lady with a silk dress, a wig and a fashionable bonnet, etc. Dame Mary Thais the same, she looked quite young. Miss English arrived and took us to the station and for the first time in my life I got into a train and was whisked off to Bath, where we arrived in about three hours. Dr English and our Abbé Lapôtre were with us. We went to see the Leigh Estate, we were much pleased with the place. We then drove to Mr Alban English’s place, Winisley Manor. Nothing could exceed the kindness of all the family.”

Unfortunately for Bath but fortunately for Teignmouth their bid for the Estate was not successful. Isabella was nothing if not persistent though:

“In September a letter from Miss English said that she and our Abbé had seen a beautiful place which she thought would be the very site for us and, as the Abbé agreed with her, she was going to sign the deed of purchase for Dun Esk, near Teignmouth, Devon. This she did, and the community agreed to advance at least £2,500 (approx £150,000 today) by the following March, to commence the building of a convent. After Miss English had settled the purchase at Teignmouth she came to spend a few days at the Hammersmith convent, and all were edified by her unassuming manner and kindness.”

In 1862 Isabella went to Rome and brought back with her a special personally signed blessing from Pope Pius IX which also blessed the convent. July 8th 1862 was the date fixed for laying the foundation stone, a ceremony carried out by Bishop Vaughan assisted by four or five priests. The Lady Abbess laid the second and Isabella the third stone. She returned to Rome in December taking with her a statue of St Peter, given to her by Isambard Brunel, to be blessed by the Pope.

The Western Daily Mercury of 10 July 1862 commented:

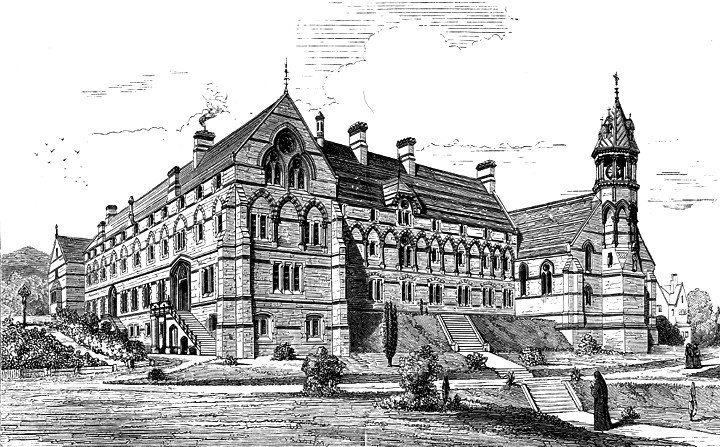

“The present proprietress of the property (Miss English) is a wealthy Catholic lady, and we understand that not only has she supplied the grounds, but also the entire cost of the undertaking. The architect is E. Goldie Esq.; contractor, Mr. S. Simpson, of London; superintendent of works, Mr James Copping. There are a large number of men now employed on the work, which seems to be carried on with great energy. Mr. Jackman, stonemason of this town, is engaged to furnish the freestone facings.”

By late 1863 the Abbey was completed. The 1867 book Devonshire described it as ‘the best piece of architecture of which Teignmouth can boast’ and quoted a total cost of £14,000 (about £850,000 in today’s money).

Later in 1872 the contemporary architect Charles L. Eastlake complimented the well-known Catholic architect George Goodie in the following architectural commentary:

“The Roman Catholic Abbey of St. Scholastica at Teignmouth is a very creditable example of Mr. Goldie’s skill. Symmetrical in its general plan, broad and massive in its constructive treatment, and pure in its decorative details, it wears an appearance at once of grace and solemnity eminently characteristic of the purpose for which it was erected, and well adapted to its picturesque site, on a hill overlooking the coast of South Devon”

Shortly before its completion the Cork Examiner of 5 November 1863 quoted the Teignmouth Gazette which gave a detailed description of the internal architecture including the following interesting snippet:

“Two chapels branch east and west from the sanctuary – one is for the use of the laity, and the other belongs exclusively to Miss English (the lady founder), who has a passage communicating therewith from her dwelling house close by.”

So the nuns finally left Hammersmith. Isabella, who was living in the adjacent house Dun Esk, took it upon herself to look after the various groups as they arrived until they could move into the convent. The Lady Abbess wrote:

“It was truly amusing to see us all at dinner at one table, decked out with flowers and all sorts of good things, Miss English at one end and the Rev. Mr Shepherd at the other. Twice our good Bishop Vaughan honoured us with his company, and seemed to enjoy it as much as anybody.”

Isabella appears to have been a regular visitor to Rome. For example, the Cork Examiner of 20 December 1869 reported on the ceremony of swearing in the great officers of the Council in the Sistine Chapel. Visitors for this event included The Empress of Austria, Archduke Rudolf, the Earl of Denbigh, the Countess of Jersey, Prince Borghese, Prince Hermann etc. The paper reported:

“The Countess English of Dunesk, and Madame Uzielli are among the latest arrivals in Rome.”

So you get a feel for the sort of circles that Isabella moved in at that time. Earlier in that year her many contributions to the Catholic church had been recognised by the Pope as reported in the Register and Magazine of Biography of that year and also as described in the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette of 29 January 1869:

“On the 8th instant our Holy Father, Pope Pius IX, conferred the honour of ‘Roman Countess’ on Miss Isabella Jane English, of Dun Esk, Teignmouth. This title has been given to her on account of her devotion to Rome and the Holy See. This estimable lady belongs, through her mother, to one of the most ancient and distinguished Catholic families in the kingdom, and is heiress and representative of the late Miss Dalton, of Thurnham Hall, Lancaster.”

The above picture is in the hall of the mansion at Prior Park college and portrays the Countess English at St Peters. Notice the bracelet on her wrist.

Isabella did participate in other non-ecclesiastical activities locally as well, for example the Royal National Lifeboat Institution Bazaar and Fancy Fair in September 1877. The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette of 13 September 1877 reported:

“No. 2 tent was presided over by Mrs. Elliott and Mrs. Holmes, and contained a tastefully arranged collection of fruit and flowers. No. 3, which was in charge of Countess English, Mrs. Arnold, and Mrs. Bathurst was (if we may be allowed to use the expression) the tent of the fair. It would be difficult to imagine a more varied collection than was to be found in it. One of the most notable things was an original drawing in Punch – ‘Trial by Battle’ – by John Tenniel, marked up at £21, which will probably meet with a purchaser before the bazaar is closed.”

Countess English – Her Later Years

By 1880 it became evident that Isabella’s health was deteriorating and she believed that the climate of Teignmouth was unsuitable for her state of health. She bought a substantial 7-bedroomed house in Gay Street, Bath, intending to move there and by September that year Lady Clifford, her two daughters and five servants took possession of Dun Esk.

She left Bath in 1884 and moved to Ulster Terrace, Regent’s Park, London. At the beginning of September 1888 news reached the abbey that Isabella had received the last Sacraments and that the doctor expected her to last no more than a few days. The book The Benedictine Nuns of Dunkirk records the events of the next few days thus:

“This announcement was most unexpected, as, although it was known that she had been suffering for some time past, she had written on August 24th that she was better. She had received every spiritual consolation, Cardinal Manning had sent his blessing and she was perfectly conscious and calm. The community was just preparing little presents to send her on the 8th, the twenty-fifth anniversary of our arrival in Teignmouth. On Saturday a telegram arrived to say that the dear Countess had died that morning and was to be buried on Thursday, the body arriving here on Wednesday. As she did not die in the convent, the lawyer sent word to say that she could not be buried in our cemetery, as that leave was only given for those who died in the abbey. The Home Secretary was appealed to, but he replied that he had no power to grant the request.”

Would this have been a disappointment to Countess Isabella English? Probably, but we will never know for certain although the Express and Echo of 6 September 1888 seemed to have some insight: “It was the wish of the late Countess to have been buried in the Convent.” The eventual burial arrangements were also unusual – a temporary grave would be prepared in the public cemetery. I can find no reference as to what was planned for after these ‘temporary’ arrangements but it is clear that ‘temporary’ became ‘permanent’ as she is still here in Teignmouth Old Cemetery.

The book continues:

“An undertaker from Bath came to make all the arrangements for the funeral and our carpenter followed his instructions. The sanctuary, Countess’s chapel, choir and cloister were all draped in black and a place prepared for the coffin. The Bishop and Canon Graham came to take all responsibility off Lady Abbess, as she was so ill. They were assisted by our constant friends, Fathers Corbishly and Urquhart, C.SS.R. They arranged everything. The Redemptorist Fathers also sang the Requiem Mass, as the community were feeling the death of their beloved benefactress so much that they felt unable to do so. Canon Lapôtre was the celebrant and Fr Urquhart the organist. The executors, Mgr Williams, Mr Parfitt and Mr King, also the undertaker, Powel, accompanied the corpse from London where she died. Mgr Williams preached the panegyric, the Absolution was given by our Bishop. Then our sisters singing the In Paradiso, the procession was formed and the community accompanied the coffin to the enclosure door. It was followed to the cemetery by a large gathering of priests and friends who had come down from Bath and London, and others who had known her in Teignmouth. As no relations were present, Mr Tozer represented the family. The Bishop of Clifton, after reading the will on the return of the clergy, went to the Royal Hotel, where luncheon was prepared by order of Mr. Shepherd, whose doctor did not allow him to come to Teignmouth.”

The Express and Echo of 6 September 1888 added this poignant fact:

“.…. the funeral oration was delivered by the Right Rev. Monsignor Williams, President of Prior Park College, Bath, who took for his text Prov. XXXI, 20 – ‘She hath opened her hand to the needy and stretched out her hands to the poor’.”

Countess English – Her Bequests

That comment is interesting because it begs the question of who are the needy and poor. Since inheriting part of Elizabeth Dalton’s estate Isabella certainly seems to have followed her condition of spending a major proportion on “charity”. But from the references I have found this expenditure seems to have been largely on the Church. The building of St. Scholastica’s is probably the most significant of her divestments but other examples included:

- Various regular contributions to Prior Park College, Bath, including: the high altar; organ for new chapel, 1882; swimming bath

- The new Roman Catholic Church, Teignmouth, 1878

- The new Venerable English College, the College Pio, in Rome, 1862 (£3000)

- The new neo-gothic style church, Eglise Saint-Jean-Baptiste, in Bois d’Haine, Belgium, in honour of Louise Lateau, a mystic and stigmatist (1873)

- St John’s Church, Bath, where her name appears on a plaque

Her will was proved on October 9th 1888 by the executors Rev. James Shepherd (her chaplain), Austin John King and James Parfitt. The estate was worth £47,000 (about £3.8 million in today’s money) and the bulk of that was left to Prior Park College (where three of her brothers were educated).

Apart from a few personal bequests there were also some specific legacies, according to the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette of 25 October 1888:

“a further sum of £2000 to found a theological chair (at Prior Park); £1,000 each to the Seminary of St. Thomas, Hammersmith, the Superior of St. Charles College, St. Charles square, and the Superior of the St. Scholastica at Dun Esk; £100 each to the Superiors of the Franciscans at Stratford and Portobello road, the Sisters of Mercy, Blandford square, and the Poor Clares at Notting-hill”

It appears that part of the legacy to Prior park may have been used to set up the Countess Isabella Jane English Foundation which closed in 2017 and, when established as a charity, had the objectives of “the promotion of education of students at the College of Prior Park or for the improvement, enlargement or repair of the said college”.

Countess English – Her Resting Place

As we saw, Countess English’s ‘temporary’ interment in the cemetery became permanent and she can be found in section F, plot 30. Her headstone is a simple Celtic cross and bears the inscription:

PRAY FOR

ISABELLA JANE

ENGLISH

COUNTESS OF

THE HOLY ROMAN

EMPIRE

AND FOUNDRESS

OF

ST. SCHOLASTICAS

ABBEY CHURCH

IN THIS TOWN

DIED SEPT 2 1888

RIP

I wonder if Countess Isabella Jane English felt that, like St. Scholastica, she would “soar to heaven like a dove in flight.”

Sources and References

There are some loose ends to the story after this main list of references.

Extracts from contemporary newspapers are referenced directly in the text and are derived from British Newspaper Archives.

Ancestry.com for genealogy

Wikipedia for general background information

Other sources, with hyperlinks as appropriate, are as follows.

St Benedict & St Scholastica

Christianity Today – reference to story of St Benedict.

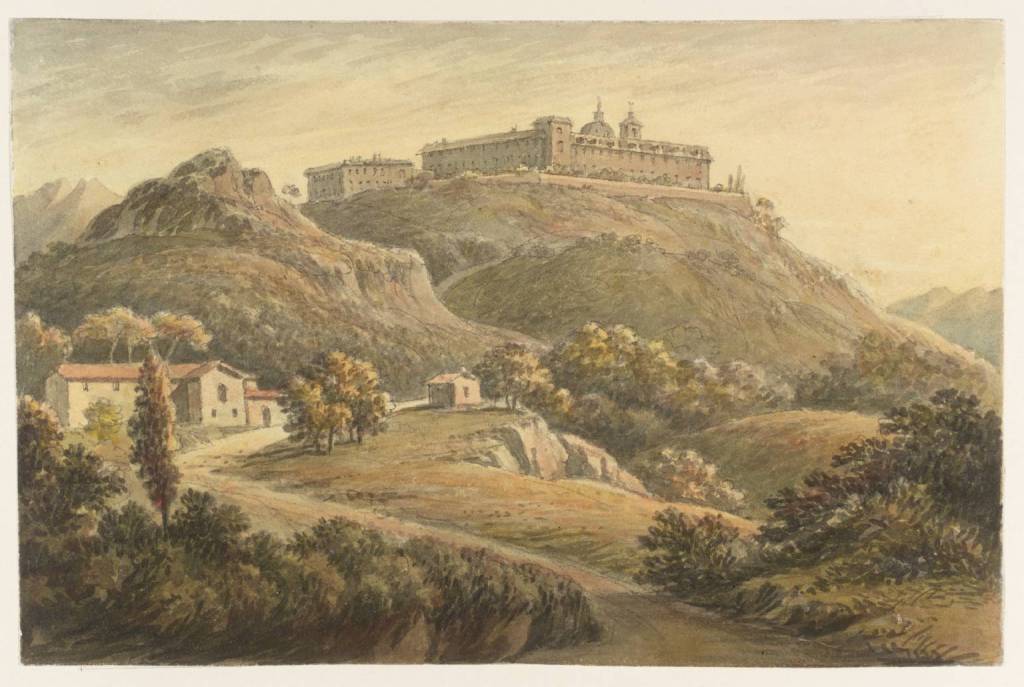

Tate Gallery – image of Monte Cassino by John Warwick Smith reproduced under Creative Commons Licence CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0. Part of the Oppé collection.

The Benedictine Nuns

A History of the Benedictine Nuns of Dunkirk, The Catholic Book Club, 1957

English Benedictine Nuns in Exile in the Seventeenth Century, Laurence Lux Sterritt, Manchester University Press, 2017

17th-century Nuns on the Run, James Kelly,

Hammersmith a Bridge, Dame Mildred Murray Sinclair, Paper 1993 Symposium,

The Religious Orders of England Vol III – The Tudor Age, David Knowles, Cambridge University Press, 1959 (repr. 2011) – reference to Erasmus and monasteries

The Dalton Legacy

Workers Housing at Glasson Dock, Andrew White, Lancaster Archaeological and Historical Society – reference to Elizabeth Dalton and inheritance.

Thurnham Hall – reference to history of Elizabeth Dalton.

Lancaster Cathedral 150th Anniversary Blog – reference to Elizabeth Dalton.

Art UK – image of Elizabeth Dalton by James Lonsdale (1777-1839), Lancaster Maritime Museum.

Countess English

The Countess Isabella Jane English, Jean English, Bristol & Avon Family History Society Journal No. 81 September ‘95 p9 (with special thanks to Bob Lawrence for tracking down the article).

Picture of Countess English at St. Peter’s, Rome. Hanging in the mansion of Prior Park College. (Special thanks to Carole Laverick for sending me photos of this picture.)

Historic Houses in Bath and their Associations, R. E. Peach, Simpkin, Marshall & Co, 1883. – references to Prior Park

The Magazine of Biography, Westminster, 1869 – notification of becoming a Countess.

The Nobilities of Europe, edited by Marquis de Ruvigny, Melville and Company, 1909 – notification of death.

The Latin Mass in the Clifton Diocese – reference to Prior Park.

A Provincial Organ Builder in Victorian England: William Sweetland of Bath, by Gordon D.W. Curtis. Routledge, 2011

The Herald and the Genealogist, John Gough Nicholls, London, 1866 – reference to Dame Mary Thais English.

Prior Park College – picture.

Old and Sold – story of Louise Lateau from 1883.

St. Scholastica Abbey

Historic England – St. Scholastica Abbey.

British Listed Buildings – listing of St. Scholastica.

The Victorian Web – reference to Abbey of Saint Scholastica (woodcut image by O. Jewitt; image scanned by George P. Landow).

A History of the Gothic Revival, Charles Locke Eastlake, Longmans, 1872 – reference to the Abbey of Saint Scholastica.

Devonshire: containing historical, biographical and descriptive notices of Exmouth & its neighbourhood, Exeter, 1867 references to the Abbey

George Goldie – biography.

Some Loose Ends

The Abbey of St Scholastica finally ceased as a convent in 1992 and was converted into residential accommodation. You rarely get to see the interior but when the occasional apartment comes up for sale there are some photographic glimpses. Here’s part of a description for one such property:

“The reception hall has a beautiful stained glass window, a holy water niche, a vaulted ceiling and marble and gilded columns. The dining hall has a vaulted ceiling as well as an intricately decorated and painted dome. There are beautiful stained glass windows set above an altar. There are further marble and gilded columns, two side altars and an ornate alabaster and onyx altar screen”

St. Scholastica, Teignmouth, may have closed as an abbey but there is a modern day one to take its place. With a motto of “Peace and Joy” and a mission statement of “contemplative life in humility, simplicity and joy within the enclosure” it was founded in 1978 in Umuoji, Anambra State, Nigeria.

James Shepherd, Countess English’s chaplain, moved to Prior Park after her death and wrote some “most interesting reminisces of that establishment.”

The High Altar donated by Countess English to the Prior Park chapel has a sepulchre for relics but actually contains no relics. According to the Latin Mass in Clifton blog:

“There are no relics in the sepulchre, but as an explanation of this fact, two traditions exist: one that the marble chest, supposed to contain the relics, on its arrival at Prior Park from Rome, was found to be empty: the other that they were destroyed by a general order from Rome, as many spurious relics were about that time sent from the Eternal City by unauthorised individuals. The relics that were to have been inserted in the sepulchre were said to be those of St Laelius, the Boy Martyr, whose name appears on the back of the altar.

It is disappointing to discover that the chapel does not, after all, contain relics of a child martyr. It seems that Countess English – or at least her agents – may have fallen prey to merchants peddling fake relics in Rome. A lively trade in forgeries such as this has been in operation since the Middle Ages, as is well known. We do not know whether St Lelius even existed. Possibly his identity was part of the deception on the part of the sellers.”

Louise Lateau was subject to intense investigation during her life and the subject of much religious adoration because of her stigmata. However her ecstasies and stigmata were insufficient for her to be canonised – an enquiry about her beatification was made again in 2009 which was turned down by the Vatican.

Countess English portrait. As Jean English comments:

“A very large portrait of her, miraculously undamaged by the recent fire, still hangs in the hall of the Mansion. Magnificently bejewelled and dressed in a long black gown and black lace mantilla, a bracelet on her wrist with a painting of the Pope, and holding a prayer book, she stands in pious splendour against a background of St. Peter’s, Rome.”

Fascinating research connected to a grave in the RC area of Teignmouth old cemetery

LikeLike

What happened to the graves of the nuns who had the Right to be buried in the Convent grounds , are they unmarked under a lawn or have they been built over ? or does a small cemetery still exist within the grounds ?

LikeLike

I am not certain Wendy. I believe that the remains of the nuns were removed possibly to Plymouth but not sure about that. The grave markers are plains metal stakes with each nun’s name on and they have been lined up against the boundary wall. I have a picture somewhere.

LikeLike

The ground where the Nuns were buried would have been consecrated by the Catholic Bishop , I seem to remember there was a time that the Church had the authority to remove graves without Government permission , now the Secretary of State the Home Office has to give permission , but it is some time since I went through Burial Law and Policy in the 21st Century , its a very long read , but it does state that a purchase of a grave plot is for 100 years not the 20 that Mark said , but that could be the accumulation that builds up after each burial in one plot . I will have to DIG further .

LikeLike