Or …..

The Curious Case Of A Teignmouth Solicitor And Babbacombe Lee

A waning crescent moon augured a dark night in Babbacombe Bay. The Cary Arms had disgorged its last customers and extinguished its lights. The “Glen”, a ‘pleasant marine villa’ long accustomed to receiving royal visitors from their yachts anchored in the bay, was tightly locked up. It’s owner Emma Keyse and her four servants were inside. It was a night fitting for murder most foul and a Victorian whodunnit …..

Teignmouth Old Cemetery has already yielded some of its secrets, proving to be an historian’s paradise. We have had tales of wealth, philanthropy, religious commitment, artistic prowess, literature, theatre and film, sea-faring exploits ….. the list goes on. But this is something new – our first crime. Not just any crime but a murder so gruesome that it shocked the nation at the time. It was reported throughout the country and has since been the subject of books, a film, an exhibit in Madame Tussauds, TV documentaries, internet blogs as suspicions grew amongst historians and criminologists that all was not what it seemed.

Because of the vast amount of documentation available about the case this story will not go into all the detail but will focus on one twist in the tale which I have dubbed “the curious case of a Teignmouth solicitor and Babbacombe Lee”.

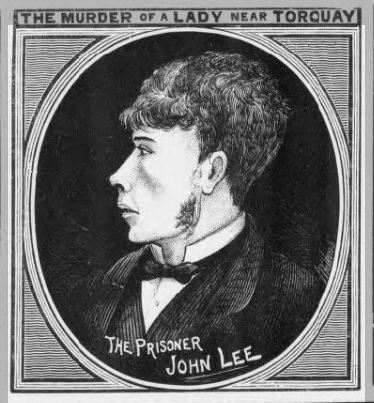

The solicitor in question is Reginald Gwynne Templer who is buried in a family plot (N47/48) alongside his father, mother, step-mother and aunt. Babbacombe Lee is the nickname given by the press to John Lee the man accused of the murder, tried, found guilty and sentenced to death. He also became known as the “man who wouldn’t hang”.

Let’s start with the crime.

The Crime

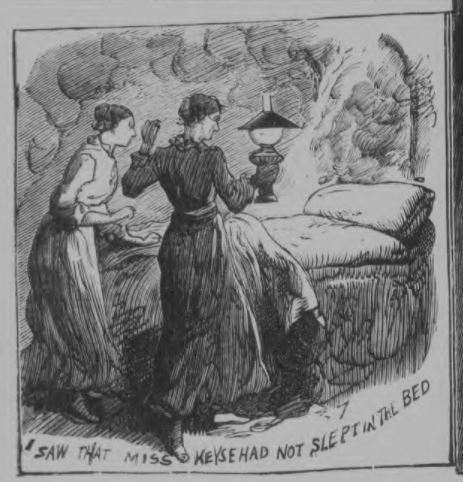

On that dark night of Saturday 15 November 1884 the first indications that something terrible was happening were the shouts. Elizabeth Harris, the cook, had woken up to the smell of smoke some time between 3 and 4am. She got out of bed and opened her bedroom door to find clouds of smoke outside in the passage and on the stairs. The house was on fire. Her shouts awoke the other two servants on the first floor – Eliza and Jane Neck – and also John Lee the butler/ footman/ gardener who slept downstairs in the pantry.

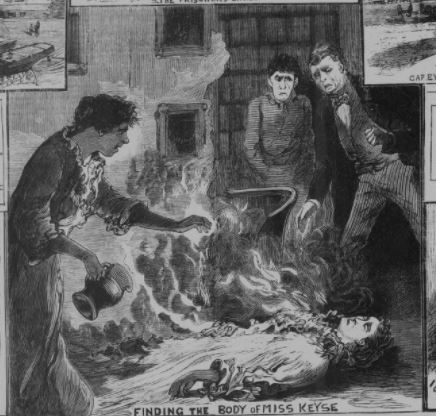

Jane and Eliza went into their mistress’s bedroom calling out to warn and rouse her only to find the bedroom ablaze too but with no sign of Emma Keyse. Whilst Elizabeth and Jane attempted to extinguish the fire in the bedroom Eliza groped her way downstairs in search of her mistress. The smoke was so thick that she could hear but not see John Lee down there in the hallway. She did see another fire though blazing in the dining room. John went upstairs to help up there and, it seems, to bring people down through the smoke. Eliza went to the pantry to fetch a bucket of water and had just thrown it onto the blaze in the dining room when John returned with her sister Jane and, as the flames died down, the three of them witnessed the grisly scene.

There, on the dining room floor, lay the body of Emma Keyse. Her head was smashed in, her throat slit from ear to ear so that her head was almost severed from her body and her body had been set alight. Her clothing had largely burnt away so that she lay there naked.

Over the next few hours others arrived on the scene to help, including the local Constabulary. Sergeant Nott seems to have made a very quick assessment that not only had a murder been committed but that John Lee was responsible. He duly arrested John Lee on Saturday morning with the words “I charge you on suspicion on having committed murder of Miss Keyse”. Lee was then taken into custody at Torquay police station.

The crime immediately received immense press coverage. Here is one example from the East & South Devon Advertiser, Saturday 22 November 1884:

“The small village of Babbacombe, about one-and-a-half miles from Torquay, was thrown into a state of excitement on Saturday, last week, by a report that an aged and well-known lady of the place had been cruelly and foully done to death. At first the rumours were believed to be exaggerated, but as the morning wore on and more details came to light, the conviction gained ground that a terrible deed had been committed mysteriously, silently, and with a fiendish disregard of other lives in the house and of the premises and their handsome contents – for all appearance point to the conclusion that the hand which did the murder, if murder it be, set fire to the house, with the intention, undoubtedly, of hiding all traces of the ghastly act”

The Judgment of John Lee

The Justice system moved swiftly. A coroner’s inquest opened in St Marychurch on Monday 17th November and completed by the end of the week with the judgment that Emma Keyes was unlawfully killed and that there was sufficient evidence to prosecute John Lee for the murder.

Accordingly the case moved on immediately to the Magistrates court in Torquay where the judge upheld this judgment and ordered that John Lee should be remanded in custody to be held for trial at the next Exeter Assizes in February 1885. There he would be tried for the wilful murder of Emma Keyse and the attempted burning of the Glen to cover up the crime and, in so doing, endangering the lives of others in the house.

There is a sense of inevitability here. John Lee was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging, the date being set for 23rd February 1885.

Then comes the first twist in this grim tale. On the night before his execution Lee claims to have had a dream that he would be led to the scaffold but that it would not work. The following day his dream came true. Three attempts were made to hang John Lee and each attempt failed, despite the fact that the hangman had thoroughly tested the scaffold mechanism beforehand and had made adjustments between each attempt. John Lee now became known as the “man who wouldn’t hang”.

The Home Secretary commuted Lee’s sentence to life imprisonment, a decision helped no doubt by a petition for clemency previously submitted by Rev. Vesey Hine, the vicar of Abbotskerswell. Interestingly Lee was released in December 1907 after serving only 23 years.

Throughout this whole process, including during his imprisonment, Lee protested his innocence. He maintained an air of calm during the trials which was inevitably interpreted in the press as at best indifference and at worst callousness. However, it seems that, in his eyes, his calmness was because of his faith as expressed to the judge at his sentencing:

“The reason my Lord, why I am so calm and collected is because I trust in my Lord, and he knows that I am innocent.” (The Secret of the Babbacombe Murder, Mike Holgate)

The Validity of the Judgment

It may be that all is not what it seems.

With the benefit of hindsight and people’s re-examination of the evidence it appears that there is sufficient doubt that John Lee was correctly sentenced. The evidence was largely circumstantial, witnesses changed their statements and there was definitely a lack of proper forensic evidence which, of course, wouldn’t have been available at that time.

It also seems that there was prejudice against him, he was badly defended (more later) and didn’t have the same financial capacity to sustain a defence as did the prosecution to resource what would have been an extremely high-profile case for the time.

The East and South Devon Advertiser of 21st February, 1885 expressed these very concerns:

“From the first there has scarcely been but one opinion entertained by the public, viz., that John Lee was the brutal murderer. So strong was the opinion even before the prisoner’s committal that there were not a few of the public who would have ignored the English mode of administrating justice, and would have inflicted lynch law upon him – in other words would have taken his life much after the same way poor Miss Keyse came to her tragic end.

Hence perhaps it was the prisoner was conveyed to the county prison from Torquay, in a carriage and pair early one morning after his committal by the magistrates instead of being taken by train. Most of the public pre-judged the man; they were impregnable to any theory that might be advanced in his defence. Even one of the jurymen at the inquest figured among the number, for he did not hesitate to make it known that if he could have his way he would hang the prisoner without affording him a trial at the Assize, and notwithstanding at the time the prisoner, acting under the advice of his solicitor, had reserved his defence.

Between the time of his committal and his trial, even in the absence of the nature of his defence, public opinion even further ripened into a belief that he was the wicked murderer, and the most wild and incorrect reports, all more or less prejudicial to the prisoner’s position, were circulated. In saying this much we do not in any way wish to exonerate the man ….. Still, whilst we believe this, we are bound in common justice to say there is room for some doubt And we do not hesitate to assert that doubt might have been greatly strengthened in our minds, as well as in that of others, if the prisoner in the outset could have commanded money in like manner as the prosecution did in netting around him strong evidence of guilt.

Very rightly the prosecution spared no expense, not a stone was left unturned in fact, to produce even the most trifling bit of evidence against him. The prisoner, on the other hand, had no such facilities. Shut up in the cells at Torquay he was debarred even an interview with his father, and though he was afterwards defended by a solicitor, that gentleman falling ill, and remaining so up to the time of the trial, he was unable to render the counsel (Mr St. Aubyn) who represented the prisoner at the Assizes but comparatively little assistance. The loss sustained in this respect must have been all the more severely felt, when two eminent counsel were engaged for the prosecution. Not only was the evidence against the prisoner very strong, but it was systematically linked together, in the absence of any material cross-examination to snap or weaken any of these links, that the jury had no other alternative but to return the verdict which they did.”

So with this background it’s worth scrutinising John Lee’s defence. Let’s start with some background to his lawyer, Reginald Gwynne Templer.

Reginald Gwynne Templer

Reginald was born in Teignmouth in the last quarter of 1857, the eldest of seven children of Reginald William Templer of Teignmouth, and his wife Emily Laurentia (neé Gwynne). His father was the nephew of George Templer who was, until 1829, the owner of the Stover estate near Newton Abbot. The family lived at The Hill, Teignmouth, a substantial property on the corner of Woodway and New Road.

Following his education at Blundell’s School, Tiverton, he pursued his own father’s profession into the Law. The Liverpool Mercury of 25 Feb 1880 marked his entry:

“THE INCORPORATED LAW SOCIETY – At the examination for honours of candidates for admission on the roll of solicitors of the supreme court, the examination committee recommended the following gentlemen, under the age of 26, as being entitled to honorary distinction: ……… Second Class ….. Reginald Gwynne Templer.”

The 1881 Census shows him as a Solicitor’s Managing Clerk and by 1884, at the age of 28, he was a Solicitor, practising in Newton Abbot and living at Bridge Street. He was also an agent in Newton Abbot for the Sun Fire insurance company. So, an apparently flourishing career, coupled with his membership of the distinguished, local Templer family should have made him an eligible bachelor. But he never married, despite the evidence in the press that he moved in the social circles of the day. Here are a few examples of events he routinely attended over time:

“The Second Ladies Day for the season took place at Teignbridge on Thursday, and was attended with brilliantly fine weather …… As usual dinner was partaken of in the Pavilion between five and six o’clock, and at a later hour, after promenading on the level and well-kept ground in the cool of the evening, dancing was enjoyed for several hours to the music of Fly’s Quadrille Band, from Plymouth. There was a large and fashionable attendance (followed by long list of ladies)”

The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette Daily Telegrams, Saturday 20 July 1878

Western Times, Tuesday 31 December 1878

“FANCY DRESS BALL AT THORNLEY – A children’s fancy dress ball took place on the evening of Boxing day at the residence of J Dawson Esq …. The lawn and conservatory was brilliantly illuminated by means of hundreds of Japanese lanterns and coloured lights, supplied by Mr Hartnell, pyrotechnist, and the place presented a very fairy-like scene.”

Western Times, Saturday 20 March 1880

“BISHOPSTEIGNTON. IRISH RELIEF FUND – On Tuesday two entertainments consisting of readings and singing, were given in the large Billiard-room at Huntley, in aid of Duchess of Marlborough’s Fund for the relief of the Irish.”

Torquay Times and South Devon Advertiser, Friday 20 January 1882

“TORBAY HOSPITAL BALL. On Wednesday night at the Torquay Winter Garden the annual ball on behalf of the funds of the Torbay Hospital took place on a scale of unusual magnificence ….. Everything went with a swing, and the ball altogether was highly successful, breaking up at about four …..”

Express and Echo, Thursday 2 March 1882

“TEIGN BOATING CLUB. An entertainment, comprising a grand evening concert by lady and gentlemen amateurs, and an exhibition of prestidigitation by the well-known amateur, Dr Stradling, was given at the Assembly Rooms last evening, under the direction of the Captain and Officers of the Teign Boating Club ….. The principal performers were ….. Mr R G Templer”

Professionally, his career was developing and there are plenty of examples in the press of cases he litigated both in a prosecutorial role and in defence. Here are just a couple of examples of more serious cases which should have prepared him for the more challenging Babbacombe murder:

“THE ALLEGED ATTEMPTED MURDER AT SHALDON. At the Teignmouth Petty Sessions, yesterday, before Colonel Lucas (Chairman), Lewis Brown, Esq., and H.B.T. Wrey, Esq., Mary Ann Wickett was charged on remand with attempting to do grievous bodily harm to her husband, landlord of the Clifford Arms, Shaldon, by cutting his throat. Mr. May, of Newton, prosecuted, and Mr R G Templer, jun, defended.

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette Daily Telegrams, Tuesday 20 July 1880

Totnes Weekly Times, Saturday 2 February 1884

“THE NEWTON ABBOT CHILD MURDER. Rebecca Loveridge (39) was indicted for murdering Jessie Loveridge, her infant daughter, at Kingsteignton, on the 11th January ….. Mr Frazer McLeod (instructed by Mr R Gwynn Templer) were retained for the defence ….. The jury …. returned …. with the following verdict: ‘We find the prisoner guilty of causing the death of her child by drowning it while attempting to take her own life, during temporary insanity.’ His Lordship: Then the prisoner will be detained in the gaol here until her Majesty’s pleasure is known.”

So we have a picture of Reginald Gwynne Templer as a bit of a socialite, at the start of his legal career and with at least a couple of cases related to murder under his belt already by the time of the Babbacombe murder. You would think that his career and life would have prospered but it was not to be. Half way through the case, between the Magistrates court session and the Assizes, Reginald was taken ill, removed from the scene and sent to Holloway Sanatorium near Windsor. He did return from there and attempted to resume his career but was forced back and eventually died there on 18 December 1886.

His decline and subsequent demise was commented on by the Express and Echo of Wednesday 22 December 1886:

“.…. Mr. R. Gwynne Templer, the promising young Teignmouth solicitor, who for a time acted on behalf of the notorious John Lee, has died after a long illness, before he had reached the age of 30. I well remember Mr. Templer’s appearances on behalf of the callous criminal at the inquest on Miss Keyse in St Mary Church Town Hall, and subsequently at the formal hearing of the case before the Torquay magistrates. By that time I believe that everybody who had had to do with the awful affair were becoming thoroughly sickened of it, and I have reason to know that amongst those who shared that feeling, and whose nervous system was by no means improved by constant attention to the dreadful details for several weeks, was the late Mr. Templer.

Whether this had anything to do with the unfortunate solicitor’s illness I cannot of course say, but it is nevertheless a fact that soon after he, in common with other persons professionally concerned in the case, had expressed his relief at the commital of Lee for trial, his health gave way, and when the case came on for hearing at the Assizes at Exeter – now nearly two years ago – Mr. R. G. Templer was unable to attend, and his place as solicitor to instruct the counsel for the defence (Mr. St. Aubyn) had to be taken by his brother, Mr. Charles Templer, who very efficiently carried out the duties which thus devolved upon him.

After being laid aside for several months, Mr. R. G. Templer had so far recovered as to be able to partially resume practice. Those who knew him, however, soon noticed that he was in anything but a satisfactory state of health. Still, with the pluck and courage characteristic of the Templers, he held on and did his best for his clients until one day, at Newton Police Court, serious illness again attacked him, and he was obliged to give up. It was hoped that another long rest might have the effect of restoring Mr. Templer to health. But it was not to be. He gradually grew worse, and on Saturday he breathed his last in London, to the regret of a large circle of friends.”

Holloway Sanatorium was in fact a specialised establishment for treating the mental illness of the middle-classes. Officially Reginald died of “general paralysis (or peresis) of the insane”. This was the euphemistic Victorian description of tertiary syphilis Although now this can be readily treated with penicillin that treatment was obviously unavailable in Victorian times and death inevitably followed usually within three years. Patients would show symptoms such as: sudden personality change, radical alteration of previous ethical and moral standards, development of extravagant and grandiose behaviour, progressive dementia.

So in reality perhaps Reginald Gwynne Templer was viewed as a bit of a black sheep of the family.

The Defence

Reginald Gwynne Templer was engaged to represent John Lee only after the start of the inquest, and judging from the transcripts of proceedings in the press he did not do a good job. He was not always present at the hearings which meant that John Lee was obliged to defend himself. He did not provide an effective challenge to the prosecutor’s evidence and he also seemed to antagonise the Chairman of the court unnecessarily with irrelevant questioning. He failed to provide a counter defence – in fact he was not even present on the final day of the magistrates court and told John Lee to say that he was going to reserve his defence (i.e. not present further information) until the Assizes.

The final nail in the coffin of the defence though was possibly when Templer withdrew from the case on the grounds of ill health as described above. This meant that Mr Molesworth-St. Aubyn MP, John Lee’s counsel at the Assizes, had no-one to rely on who had intimate knowledge of what had happened previously and the finding by the court of John Lee’s guilt was almost inevitable. He was also defending a number of other cases at the same time and was under such time pressure that he even requested a delay in the case as the Western Times of Monday 2 February reported:

“The Counsel engaged in this case pleaded for a later opening of the Court, as the witnesses from Torquay would have to leave at half-past seven in order to be here in time, and Mr. St. Aubyn, who defends the prisoner, had not had time to inspect the premises, and it seemed to be thought that the learned gentleman …. would have to go there on Sunday – at the peril of being prosecuted under the Statute, for following his usual occupation on the Lord’s day.”

There was a suggestion that a line of defence of insanity on the part of John Lee should have been used. In fact this was the main contention in the petition sent to the Home Secretary by Rev. Vesey Hine:

“His parents, who are respectable people living at Abbotskerswell, in the county of Devon, consider that he is suffering from a deranged state of mind, he having from his youth upwards shewn at times symptoms of temporary insanity.”

According to the East & South Devon Advertiser of Saturday 21 February 1885:

“It is perhaps to be regretted speaking in behalf of the prisoner, that another kind of defence had not been set up, viz., that of insanity. We believe that if that course had been pursued the issue might have been very different. This is not merely our views but those of others who are far better able to form an opinion of the prisoner’s state of mind than we are.

.… owing to a variety of incidents coming to light, and the eccentricities the prisoner was known to indulge in from time to time, many people consider that his right state of mind is very questionable. His parents assert most positively that from his youth upward he acted at times ‘as though he was not right’, but that they never divulged their suspicions lest it should affect him in getting his living.

….We should further mention that a few days since we saw the foreman of the jury who convicted the prisoner of murder. He stated that he felt most confident that the prisoner was not of sound mind, and in that opinion, he said, he was joined by several other jurymen.”

A potential second line of defence emerged during the closing speech of John Lee’s defence Counsel, Mr Molesworth-St. Aubyn, although it would appear that he had not actually pursued this during the trial. This was how it was reported by the Cardiff Times of 7 February 1885:

“The long looked for speech for the defence was then commenced and listened to with eager interest. Mr. St. Aubyn spoke as though fully impressed with the responsibility and difficulties of his position, but put his case in a practical way and without much attempt at enlisting the sympathies of the jury. The theory which he advanced that the crime was committed by the lover of the prisoner’s half-sister seemed to produce little or no impression, and it was subsequently felt that it had been pithily described by Mr Justice Manisty as a ‘far-fetched idea’. The facts adduced by the prosecution were virtually allowed to go unchallenged, and Mr. St. Aubyn did not dwell so minutely as was expected on those portions of the testimony which were admittedly weak or at variance. He solemnly cautioned the jury as to the responsibility which rested upon them in dealing with purely circumstantial evidence, and held out to them the example of Habron, wrongly convicted of a crime committed by the notorious murderer Peace, as showing the occasional unreliability of such testimony. Finally, he appealed to the jury to give the prisoner the benefit of any doubt they might entertain, and sat down after an address of half an hour.”

John Lee’s half-sister was Elizabeth Harris, the cook in Emma Keyse’s house who had been the first to discover the fire. She was approximately two months pregnant at the time (her daughter Beatrice was born 24th May 1885 in the Union Workhouse, Newton Abbot) and the argument behind St. Aubyn’s theory was that the unknown father was in fact some local person of note – possibly his identity had been discovered by Emma Keyse who may have threatened to disclose it and provided the motive for murder. That idea, coupled with John Lee’s continuing protestation of innocence whilst in prison, has been at the nub of the mystery surrounding the murder ever since. It was the first inkling of another revelation some fifty years later.

The Final Twist in the Tale ….. perhaps

In 1936 the Torquay Herald Express published an article by the journalist Reg CowilI. Convinced by information he had recently received he re-opened the debate on the Babbacombe murder:.

“About the year 1890 there stood at the side of an open grave, in a South Devon town, a well-known and local resident and his two sons. The man who had been buried was a public man of the town who had been very well-known, highly respected and very popular throughout South Devon. The young men were, also, in their turn, to become public men in the area. As they were moving away from the grave and the mourners were disbursing their father turned to them and said ‘we have buried this afternoon the secret of the Babbacombe murder’.

The man concerned, and who was declared by Lee to be the murderer of Miss Keyse, was known, says our informant, to have been critically ill for a long time after the murder, though nobody knew at that time, or ever, associated him with the crime. As a matter of fact, he never really recovered, and gradually became demented. He died in a mentally unbalanced condition ….. When in his madness, he shouted things which the doctors put down to his state of mind, there were one or two people – our informant’s father was one – who knew what he was referring to, and what had driven him insane.”

The implication from the article was that the murderer was Reginald Gwynne Templer. There is still no concrete evidence of that. It is hearsay but there is also reportedly circumstantial (and unverified) evidence that Emma Keyes was connected to the Templer family and that Reginald Gwynne Templer was a regular visitor to her house.

So there is no definitive answer and many loose ends that would need to be tidied up to get to an answer. I suspect that will never happen because the real knowledge of what occurred was buried long ago in the graves of the characters in the story.

One Loose End

One aspect which has always intrigued me though was that John Lee (who, from his past, didn’t seem to be religiously inclined) appeared to exhibit a trust in God and believed that right would prevail because God knew that he was innocent and didn’t commit the murder. That was his response to the observation that he remained so calm during all the proceedings. Could “God” have been simply his translation of a local religious person knowing the facts of the case?

There was, of course, the Reverend Vesey Hine, the vicar from John Lee’s original parish of Abbotskerswell, who raised the petition to the Home Secretary. But I have also found a snippet of information about someone else which may be of relevance. It’s from the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette of Tuesday 2nd December 1884:

“The Chief Constable (Gerald de Courcy Hamilton, Esq.) and Superintendent Barbor were present to watch the proceedings on behalf of the police authorities; and Mr. R.G. Templer appeared for the accused, John Lee, who, as on the previous similar occasion, was not brought into Court. Among those who occupied the reserved seats was the Rev. J. Hewitt, Vicar of Babbacombe.”

Normally this would have passed me by but Rev John Hewitt is buried too in our cemetery and I wrote up his story recently (click here) .

It struck me as odd that he should have been interested in attending the inquest unless he had some involvement. It is also odd that the paper picked him out from everyone else who had reserved seats. It could have been that he simply knew Miss Keyse but it could also have been because of the cook, Elizabeth Harris. Why? If you read his story you’ll see that coincidentally his own wife had died earlier that year and he was closely involved with organisations supporting young women (the Sisters of Mercy at Bovey and the House of Rest in Babbacombe). The fact that Elizabeth Harris was pregnant and single might suggest that he was aware of her and perhaps knew who the father was and that exposure of the father could have been a motive behind the murder. We may never know.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for help I have received from Stuart Drabble (local historian and secretary of the Stover Trust) with aspects of the Templer family. A book of his on the “Stover Park History & Connections” is due for publication soon and should make fascinating reading.

Sources and References

Extracts from contemporary newspapers are referenced directly in the text and are derived from British Newspaper Archives.

Ancestry.com for genealogy

Wikipedia for general background information

Other sources, with hyperlinks as appropriate, are as follows:

The Secret of the Babbacombe Murder, book by Mike Holgate, Peninsula Press, 1995,2001

Templer Family Genealogy

Murder Research website, Ian Waugh, comprehensive write-up of all aspects of the Babbacombe murder,

Pictures – the Illustrated Police News and the Penny Illustrated Paper were invaluable sources

Histories of Things to Come, website carrying Babbacombe murder story – “Strange Tales from a Seaside Town”

Institutionalizing the Insane in Nineteenth-Century England, Anna Shepherd

Studies for the Society for the Social History of Medicine 20, Pickering & Chatto, 2014 – history of Holloway Sanatorium

Notes on Templer Burials in Teignmouth Cemetery, Stuart Drabble

Wow I love these histories that you uncover. I have read the book ‘ The man they couldn’t hang’ . Keep up the good work.

LikeLike

Thanks Barbara. It’s fun doing the research as well and keeps me occupied during lockdown.

LikeLike