Beneath the Weeping Lime

The weeping lime in Teignmouth Old Cemetery hides many secrets. Stretching low across sections T and U in the older part of the cemetery its canopy covers graves which lie invisible for a large part of the year. When autumn approaches though and the leaves burnish and fall, the secrets are revealed.

One of those secrets is Autolycus, the son of the god Hermes and Chione in Greek mythology. He inherited the arts of theft and trickery from his father, and he could not be caught by anyone while stealing. It was also the pseudonym adopted by Thomas Henry Aggett, the ‘Railway Poet of the West,’ when publishing his books of verse.

Early Years

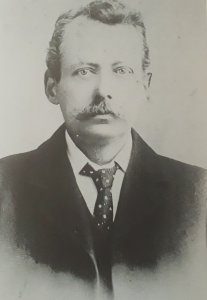

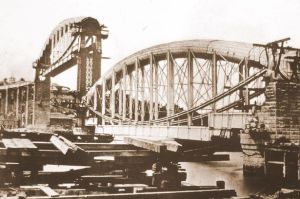

Thomas Henry Aggett was born in July 1863 at Saltash in Cornwall where his father had been working under Brunel on the construction of the famous Royal Albert Bridge. The bridge had been formally opened in 1859 but presumably the work continued beyond then and on completion of that work the family moved to Torquay.

There Thomas, at the age of ten, started work as a farmer’s boy. This seems a somewhat inauspicious start but it appears that Thomas had some aspirations because in 1880 he moved to the Isle of Wight where he served as a footman for two years in the household of an invalid widow lady. There was a fine library in the house which Thomas apparently used to the full and kept himself in a regular supply of literature. He had to be a little surreptitious though since the house-keeper did not approve of this activity. It was then that he first became acquainted with the works of Burns and Byron who became his favourite authors. He would read them again and again until he knew nearly the whole of their poems by heart.

The Railway Years

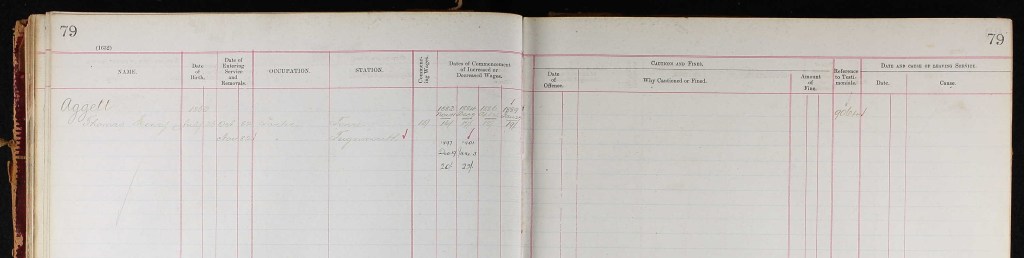

Whilst Thomas was working there his father died (1881) at the young age of 52 and In October 1882 Thomas joined the Great Western Railway (GWR) at Tovil in Kent. He moved with them the following month to Teignmouth where he worked as a porter, although living at that time in Torquay. He spent the rest of his working life with GWR, retiring early in 1901 on the grounds of ill-health. By then he was a foreman porter. An interesting aspect of social history can be found in his railway record which showed his wages rising from 15s (or 75p in modern terms) a week to the princely sum of 22s a week 18 years later. According to the Victorian Web this would have been on a par with farm hands and sailors. By comparison the Governor of the Bank of England was then earning around £8 a week.

In 1885, at the age of 22, he married Emily Lavis, the daughter of a tailor in Newton Abbot. They went on to have five children. Mabel Jane, was born on 23 January 1886 whilst they were still living in Torquay. By 1887 the family had finally moved to Teignmouth and Robert William was born there on 14 April. He was followed on 15 September 1890 by Herbert Edmund, when they were living at 4 Parson Place. Their next son, Thomas Henry, arrived two years later on 24 May 1893 and it was another seven years before the birth of their final child, Ernest Harry, in 1900. By that time the family had moved to 5 Gardener Farm in Frogmarsh Street – this would have been off Lower Brook Street somewhere in the area below the railway station which had once been the marshland through which the river Tame flowed as it meandered down through Teignmouth to emerge into the Teign by what is now Somerset Place.

So we have a picture of Thomas living a “normal” family life in a steady job but that job could bring its own trauma. Here is a story from the Teignmouth Post and Gazette of 15th April 1898:

“THE CASE OF ATTEMPTED SUICIDE AT THE RAILWAY STATION

NO FOOD. NO HOME. NO MONEY”

“At the Town Hall on Tuesday, before Col. Nightingale (Chairman) and Mr F. Slocombe, Charles Pratt, a middle-aged man, of no fixed address, was charged with ‘throwing himself in front of a train with intent to murder himself’.

The prosecution was in the hands of the police. Prisoner who was pale, had his left arm in bandages. He had every appearance of having undergone a great shock to his system, and was allowed to sit during the hearing.

William Henry Pellow, goods checker at Teignmouth railway station, stated that on Saturday evening, the 19th of March, he was on the platform awaiting the arrival of the 6.40 from Exeter and due at Teignmouth at 7.0 o’clock. When the train was coming in and the engine nearing the bookstall, he heard someone shout. Witness could not tell the exact words, but it was like ‘Here goes’, or something to that effect. Witness saw a man (the prisoner) run towards the edge of the platform and jump off. He pitched on his feet in the centre of the permanent way. Seeing the man was in danger, witness turned his handlamp to red and waved it to attract the attention of the driver, who saw the signal and applied the vacuum brake and the train was pulled up. The man was the length of the engine ahead of the train. Witness at once reported the matter to the station master, and then went to where the man lay under the carriage. The engine and a coach and a half had passed over him. Witness had seen prisoner in the station yard before six o’clock on the same evening. He had no reason to believe that the man had been drinking.

William Kibbey, of Lower Brook Street, said he was standing on the down platform on the night in question at about ten minutes to seven. Witness noticed prisoner there and when the engine was just opposite the bookstall he ran towards the line and jumped off, about ten yards in front of the train that was running in. He pitched on his feet and turned around and faced the engine. Witness shouted to him to clear off the line; he took no notice of the warning, but threw himself forward towards the engine and fell flat on his face. He was not struck by the front of the engine; his injuries must have been received as the engine passed over him.

Thomas Henry Aggett, porter in the employ of the Great Western Railway, stated that on the Saturday evening in question, he had just locked the door where the tickets are collected as the 7.0 o’clock train was running in. He heard someone shout that a man was under the train. Parcels-porter George Honywill ran around the front of the engine and witness went down between the carriages and crawled underneath. Prisoner was lying under the second coach from the engine; on his back, and was bleeding from a cut on his head. Whilst they were examining his legs, before moving him, prisoner said ‘Let me get up. I can’t breathe.’ When they had moved him a bit, he asked for some whiskey and water. He was shifted from his position and a doctor was sent for, and the house-surgeon at the hospital came with a stretcher.

Mr. J. Shera, house-surgeon at the hospital said he was called and informed that an accident had occurred at the railway station. When he got there, he found a man (the prisoner) lying in the six-foot way, and bleeding profusely from the head. He was removed to the hospital, and on further examination witness found two large incised wounds on the scalp; a fracture of the skull; and a comminuted fracture of the clavicle-or left collarbone. Prisoner was sober, but the shock had affected his mind. So far as witness could judge, he should consider the man was accountable for his actions.

W. Pellow recalled: There would be barely room under the class of engine running that train for a person to escape. The road being level the bogie plate would strike the man first.

Constable Martin deposed that he was outside the station gates and was informed of what had happened. When prisoner was removed from beneath the train, witness helped to carry him to the hospital. Ever since the 19th March, a constable had been watching him night and day. When searched he had neither money or railway ticket. Before witness charged prisoner with attempting to take his life, he cautioned him in the usual way. Prisoner said “Well, I was very hard up; I could not beg, and I was never before a magistrate in my life.” Sergeant Richards said they had been in communication with a sister of prisoner residing at Dawlish, and she said she had not seen her brother but twice in twenty years, and positively declined to be responsible for him in any way. From what witness could learn, prisoner was a smith and had worked for a railway company somewhere near London. He had other relatives who refused to take charge of him. Prisoner had informed him (Sergeant Richards) that he was married but where his wife was he did not know.

Prisoner having been asked if he had any defence stated that he was out of work and had been as far as Dartmouth to get something to do and could not get a job. He had not had anything to eat for three days and only a drink of water on the road. He had no money or place to go to, and it was so many years since he saw his sister at Dawlish he had forgotten her address. It was the first time he had ever been before a bench of magistrates in his life until now. The Chairman said it was clearly a case to go to the Assizes. Prisoner would be granted bail in a surety of £3, failing to get that, he would have to go prison to await his trial. Prisoner said he did not know of anyone who would become surety for him.”

Apart from incidents such as this, life as a railway porter would inevitably been one of routine. How many of them would have broken that routine with outside interests? The Totnes Weekly Times of 25th January 1890 explored that very issue:

“RAILWAY POETS AND ARTISTS

Teignmouth Railway Station has, says a contemporary, its poet in Mr Thomas Henry Aggett, author of ‘The Demon Hunter,’ and Moretonhampstead Station can boast of having in two of its porters, Messrs W. J. Barnicott and George Koodes, amateur artists of much ability ……. Considering their long hours of labour, these railway servants deserve the greatest praise for devoting their very little leisure to such intellectual pursuits.”

One wonders what Thomas might have achieved if he had been born in different social circumstances, had received a formal education instead of working as a farm-hand from age 10 and had been given the opportunity that would have afforded. His love of poetry has already been mentioned but he appears to have been well-read and knowledgeable outside that arena too as evidenced by a letter he wrote to the Western Morning News of 25th November 1892:

“THE COMET IN ANDROMEDA

Sir, – ln your issue of 23rd inst. I notice that Miss Macnamara makes some startling statements with regard to Holmes’ comet. She says that she has found by calculation that it is Biela’s comet which was discovered 1826. This, according to Sir Robert Ball, is not the case, and I would direct her attention to an article on the subject in the Daily Graphic of the 23rd inst. by that eminent astronomer. She goes on to say that Biela appeared in 1846 under the form of two comets of unequal size. This, I believe, is generally accepted as true; but then she proceeds with her most remarkable statement – “Now what has become of the smaller one? It, undoubtedly, was captured by Jupiter about three years ago in crossing its orbit, and now appears in the form of its fifth nearest and smallest moon.” Surely she does not consider that in the amazing short space of three years Jupiter has pulled one part of Biela from following a very elongated ellipse to that followed by Jupiter’s inner satellite- Let us hear what Professor Barnard says, who discovered the satellite in question: – “The latitude measures of the satellite shew that its orbit lies in the plane of Jupiter’s equator, and consequently the satellite is a very old member of Jupiter’s family.” Lastly, it appears she is going to dispute with Professor Barnard the honour of discovering the satellite. Professor Barnard discovered it on the night of September 9th last, and Miss Macnamara says her family saw it on September 4th, but I understand that it cannot be seen with an instrument under 26in, of aperture, and then only under first-class conditions; and I doubt very much if Miss Macnamara possesses a telescope of this size. But perhaps she will enlighten us this point. – Yours Truly, Thomas Henry Aggett, 4 Parsons Place, Teignmouth.”

This was cutting-edge science at the time. The appearance of the comet was much reported and people in Teignmouth were reported as waiting up to view it, also in expectation that it could enter the earth’s atmosphere and provide a spectacular pyrotechnic display.

The fifth moon of Jupiter was named Amalthea and was the only moon, other than the first four observed by Galileo, to have been discovered by direct visual observation.

Aggett The Poet

One of the perks of being a railway employee appears to have been access to free rail travel, which brings us back neatly to Thomas’s major interest – poetry. He has recorded that in October 1883:

“I paid a visit to the ‘Land o’Burns’ having a week’s leave, with a free pass to Manchester and back. I started on my pilgrimage as devoutly as every good Mussulman started for the shrine of Mohammed at Mecca, and never have I so thoroughly enjoyed myself as I did that week in visiting the places of interest connected with Scotland’s national bard.”

Thomas seems to have had an affinity for poetry from an early age because he remembers that, when very young, he used to hum over his favourite tunes adding words of his own that would suit his particular fancy of the moment. In this respect he has actually been compared to Alexander Pope as someone who “lisped in numbers”, which seems to mean having a natural inclination to think and/or express oneself in a metrical rhythm. Pope revealed this in his letter to Dr. Arbuthnot:

“Why did I write? What sin to me unknown

Dipt me in ink – my parents’ or my own?

As yet a child, nor yet a fool to fame,

I lisped in numbers, for the numbers came.”

Thomas’s love for poetry led him to publish his own works. In 1889 he issued a brochure entitled the ‘Demon Hunter, a Legend of Torquay’ (publisher Ebenezer Baylis) which included pieces such as the title-poem – the ‘Demon Hunter’ – ‘The Parson and the Clerk,’ ‘The Mayor of Bodmin,’ and others dealing exclusively with local legends. This was followed in 1894 by a little volume entitled ‘Vagabond Verses, Through the Coombes and Vales of Delectable Devon’.

What was he like as a poet?

There’s an interesting comment about his poetic style in the book ‘West Country Poets’ of 1896:

“It may be readily understood that a man employed at a busy railway-station can have but little leisure for the cultivation of the Muses, and this fact must condone many imperfections in the published works of our railway poet.”

This may sound a little disparaging or patronising but the local reviews of his works were much more upbeat at the time. There are many to choose from. Here is an example from the Western Morning News of 17 March 1905:

“The poems printed here ….. display considerable poetic feeling and power of expression ….. The author writes with commendable smoothness and finish, and displays a turn of humour which renders many of his verses very entertaining reading”

Thomas Aggett himself was honest enough to recognise his limitations. In the preface to his first volume he wrote:

“I do not aspire to genius, neither do I pretend to have written anything exceptionally good, and if the reader derives the same amount of pleasure in reading as I have in writing the poems, I shall consider it sufficient recompense, and feel justified in having printed them; if, on the other hand, they are found incapable of affording any pleasure, I can only excuse myself, by saying they never would have been printed had it not been for the hope of benefiting the Widows and Orphans’ Fund of the Great Western Railway”.

Returning to that short clip from the Western Morning News it’s worth looking at the article in full which reveals more about Thomas, the man:

“VAGABOND VERSES: THROUGH THE COOMBES AND VALES OF DELECTABLE DEVON.

By Autolycus. (Hartnell, Teignmouth, 1s) – Prefixed to this modest little volume of verse is a note on the author by Mr. W. H. K. Wright, of Plymouth, to which is added a statement by Mr W. G. Hole, stationmaster at Teignmouth, where the author is employed as a foreman railway porter, that his ill health prevents his attending to his duties for any length of time, and that he will shortly have to retire. This volume is now published in the hope of recouping by its sale the expense he has incurred by three or four years illness. Mr. Wright’s note gives a brief sketch of the life of ‘Autolycus’, who in everyday life is Thomas Henry Aggett. A native of Saltash, he worked as a farmer’s boy. and then became a footman in a household where he was able to spend much of his time in a fine library, by means of which he was able to cultivate his natural taste for letters. In 1882 he became a railway porter, and has remained one ever since. The poems here printed, though largely imitative in style, display considerable poetic feeling and power of expression, and coming from such a source are not a little remarkable. The author writes with commendable smoothness and finish, and displays a turn of humour which renders many of his verses very entertaining reading. His subjects are largely, indeed chiefly, drawn from his adopted county Devon, by whose leading residents, as the subscription list at the end of the volume shows, the book has been largely bought. Apart from the worthy object of helping a deserving Westcountryman, the poems are worthy of a wide circulation for their intrinsic merit.”

Although never a mainstream poet his life history is fascinating and, as suggested by the above article, he uses poetry to capture anecdotes of his time, snippets perhaps of social history. Here are some examples:

Eulogy to Dr Robert Hamilton Ramsay

This is a long poem which was also later reproduced in full in the Torquay Times and South Devon Advertiser of 10 May 1907. The article refers to “Mr Thomas Henry Aggett, ‘The Railway Poet’, who, during a long illness, had much reason to be grateful to the late Dr Ramsay.” Only the first verse is reproduced here to give a feel for the style and tenor of the poem:

Since thou art mindful of the needy poor,

Whose welfare in this world so few consider;

In honour of thy worth the Muse would soar;

Worth is our standard and we never did err,

Or like the mercenary bards of yore,

Sell panegyrics to the highest bidder;

Worth is alone rewarded with an ode

Or song from our Parnassian abode.

The Great Western Railway Record Run, May 9th, 1904

It is only fitting to include something that Thomas would definitely have been proud of – the longest and fastest Non-stop Railway Run, London Paddington to Plymouth (245⅝ miles) in 3 hours 53⅟₂ minutes.

Speed! From the West!

Steam in the service of man!

Great Western, you hold of records the best.

‘Twas work well done in a stiff contest,

Of brawny arms of a brainy clan –

A credit to every man.Through our County of cider and cream,

Flying soft and as swift as a bat,

It shows us the triumph of steam,

And the triumph of brains over that.More problems for us to unravel,

Dame Nature still holds in her greed,

Then where is the limit of travel,

And what is the limit of speed?

Bridget of Brimley

Brimley now is a developed residential area of Teignmouth but in Aggett’s time would have been largely farmland, with Brimley brook formerly being a feeder for the River Tame which once flowed into the centre of Teignmouth where it formed a marshy confluence with the Teign. This poem is an interesting example of customs of the time which might otherwise have disappeared from memory if they hadn’t been recorded in rhyme, whether that be poetry or song. It is also of a similar ilk to Keats’s “Devon Maid” – perhaps that was part of the inspiration.

Now Sweetheart be good,

And don’t be contrary,

Pray put on your hood

And lock up the dairy,

Together we’ll roam,

Ay, trip it so trimly

Through the meadows and home,

Come, Bridget of Brimley.Here’s a grass, tell our lot,

You witch, read it steadily;

“We love” – “we love not” –

“We love” – ay so readily.

But throw now I pray

Light where I see dimly

The hour and the day

Bright Bridget of Brimley.

The book ‘Vagabond Verses’ explains:

“The kind of grass here alluded to is the perennial rye-grass, locally known as ‘Eaver’ which Devonshire maidens are wont to pluck to ascertain of what trade their future husbands will be. Starting from the top ear they chant the following:- ‘Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Sailor, Richman, Poorman, Beggarman, Thief’ – repeating (if necessary) until the last ear is touched wherein resides the oracle. Children in play in the meadows have a similar custom; when in doubt as to the passage of time they take a grass and say – ‘Does my mother want me? Yes – no – yes – no’ and so on.”

Eaver by Maureen Fayle

Address of Teignmouth to her Local Board

As a final example of Aggett’s poems here is one scathing commentary which, some might say, reflects the unchangeable nature of local politics and decision-making:

With lamentations loud and deep

Great cause have I, alas! to weep,

My Council members seem asleep,

I’m so dejected

For I whom they profess to keep

Am quite neglected.By Nature clad in beauty’s dress,

Ye members surely must confess

What great attractions I possess,

Which you abuse,

When you could much improve I guess

Me if you choose.But no, a dilatory curse

Seems settled on you, quite averse

To all improvements, worse and worse.

Your attitude

And money from the public purse

Does me no good.I cannot now enumerate

Your foolish actions, neither state

Your time-waste in so-called debate;

With grief I see

Less water for more water-rate;

But list to me –Just cease your foolish altercation,

My visitors want recreation,

Give this your best consideration,

You must agree

If you desire not condemnation,

Attractive be.And to the public weal attend

In future better, and amend

The foolish way in which you spend

The public pence,

And pray that Providence will send

You better sense.

The feeling behind this poem might well have been a driver for their third son (also Thomas Henry) entering local politics.

In Memoriam

So, in summary, Thomas Aggett was a man of humble origins, self-educated, with an eye to social justice and with a love of poetry. Like his father he died young. In his later years Thomas went through a long illness, had to retire early and was only 43 when he died on 14th October 1906. As befits a poet he had written his own short epitaph:

“Scorn not this humble grave, turn not away,

Ashamed to shed a sympathetic tear;

With reverence to this shrine thy homage pay,

A poet’s sacred dust reposes here”

There were several obituaries of Thomas published in the local press. Here is an extract from the Western Times of 16th October 1906:

The Railway Porter Poet Dead.

Mr. Thomas Aggett, well-known in the West of England as the ‘railway poet’ is dead. He was formerly foreman porter at Teignmouth railway station, but failing health necessitated his taking rest, and his recovery being doubtful he was unable to return to his duties on the platform. A short time since he was granted the privilege by the G W Railway of being a town porter at Teignmouth. On Saturday he had been to Plymouth to see his brother, and on Sunday morning he passed away. He occupied much of his time in writing poetry, and published three books, one entitled ‘Vagabond Verses’, and another with the title of the ‘Demon Hunter, a legend of Torquay’; the proceeds of the sale were given to the Widows and Orphans’ Fund of the G.W. Railway. He was a modest and unassuming working man. He suffered from an affliction of the heart …..

The remainder of the obituary contains the extracts included earlier on his view of his own poetry and the epitaph he wrote.

Thomas Henry Aggett is buried along with his wife Emily, who died in 1925, in plot T156 beneath the weeping lime. Their daughter, Mabel Jane, and sons Robert William and Thomas Henry are also buried in the cemetery. Herbert Edmund also joined GWR, married and died in Tolworth, Surrey. Ernest Harry became an engineer with the GPO and died in Honiton in 1957.

Sources and References

Extracts from contemporary newspapers are referenced directly in the text and are derived from British Newspaper Archives.

Ancestry.com for genealogy

Wikipedia for general background information

Other sources, with hyperlinks as appropriate, are as follows.

‘West-Country Poets: Their Lives and Works’ by Wright, W.H.K., (1896) On-line version: West Country Poets

https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/Mortals/Autolycus/autolycus.html – background to Autolycus

https://www.britannica.com/place/Amalthea – Jupiter moon

Bilea comet – By Secchi / Guillemin – World of Comets, A. Guillemin, 1877 (U.S. edition), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47581940

https://www.bartleby.com/library/poem/4124.html – Alexander Pope poem

https://www.bartleby.com/209/693.html -Henry Craik, ed. English Prose. 1916.

Vol. III. Seventeenth Century

Porter, Dale H. The Thames Embankment: Environment, Technology, and Society in Victorian London. See for example http://victorian-era.org/the-victorian-era-wages-salary-earnings.html

For more examples of Thomas Aggett’s poetry search the catalogue in “Teignmouth in Verse” (https://keatsghost.wordpress.com/). Alternatively track down “The Demon Hunter: a Legend of Torquay”, published by Ebenezer Baylis, 1st January 1889; and “Vagabond Verses… Through the Coombes and Vales of Delectable Devon”, 1904.

Very Interetsing thank you!

I had the privilege of knowing Noreen Mardon – a daughter to one of Thomas’s sons- not sure which. She and her sister attended Teignmouth Grammar School. she married John Mardon a missionary and they worked abroad. Retiring back to Teignmouth they lived in Pennyacre. She was a great church woman and in late life moved away to live near her son. I imagine she will have passed by now

Viv

________________________________

LikeLike

Thanks Viv. Sounds like Noreen could have had an interesting life too. Part 2 of this story is going to be Thomas Henry Aggett junior – the son. He is also buried in the cemetery and appears to have been very active politically (local and national politics) – he fought Nancy Astor for the Plymouth seat in the general election. I’ve tried to track the Aggett family locally but they all seem to have disappeared now – probably later generations gradually moved away. Neil

LikeLike

Hello Everyman

You’ll see from my reply to Viv’s comment that I am the youngest of Noreen Mardon’s (née Aggett) five children; great grandson of Thomas Henry Aggett the railway poet and grandson of Thomas Henry Aggett his son. Noreen had two sisters, neither of whom had children. I believe the only other descendent of the railway poet’s children was Doreen, only daughter of Ernest. She married and had one son. Doreen died earlier this year in Fareham, Hampshire where she had lived for over forty years.

I and my brothers and sisters may be able to help with your research for part two of your story. There is a lot of information about him in Teignmouth museum but we have a stack of material documenting his fascinating life. Similarly both Noreen and Jack led full and interesting lives.

Do get in touch if we can assist

Steve Mardon

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Steve. Thanks for getting in touch with us. I’d be very interested in anything you might have about your grandfather. I already have quite a bit from newspaper cuttings waiting to be put together as a short biography when time permits! I’ll email you separately. Regards, Neil

LikeLike

Hello Viv

I’m the youngest of Noreen’s five children. She indeed passed on aged 89 in May 2013. Her father was Thomas Henry Aggett (the younger). She had two sisters – Elaine and Vivienne – both also now gone on.

Noreen became a master printer in her father’s business, first in the railway station yard and later behind the Methodist Church in Somerset Place. She married John Hedley “Jack” Mardon who had grown up in Boscawen Place, Teignmouth and worked in the shipyard. Jack was in The Royal Engineers during and after the second world war. Both staunch members of St James’ Church they went in 1949 to Lainya, Equatoria Province, Sudan with the Church Missionary Society. Noreen ran a medical dispensary providing basic care to the local community – the only medical facility within a day’s drive. Jack was a teacher of construction skills in the technical school.

On their return to UK in 1961, Jack trained for the ministry holding posts in Taunton, Cullompton and Locking, Weston super Mare. He died suddenly in 1989 and Noreen retired to the house in Pennyacre Road.

I’ll add further comment below to Everyman about Noreen’s father.

LikeLike

Thanks Neil great research as usual from you👍

BTW I just saw Geoff Yarwood in town he said thanks for email which he saw in time so he didn’t head off to Smugglers last week 🙂

________________________________

LikeLike