A few weeks ago Jacqui, one of the dedicated group of volunteers of Friends of Teignmouth Cemetery, discovered and uncovered a grave in section HH of the cemetery. Her first reaction was “There’s a story here”. That instinct was not wrong but she had under-estimated. There were three stories – people buried in different parts of the cemetery but linked through this discovery.

A seven year old girl, Frances Maude Waite, tragically killed by a runaway traction engine on 12th June 1896, was the subject of the first story. This second story is about Sidney Charles Wills whose life could perhaps have been so much more but which turned from triumph to tragedy.

The Start in 1900

This story starts in 1900, in the dying days of Victorian imperialism when Britain was deeply mired in what was known in Britain as the Second Boer War, which the Boers acclaimed as the “Freedom War”, and which is now conventionally referred to as the South African War. The war itself started in 1899 and it wouldn’t be over-simplistic to say that greed was a prime instigator of the war. The Kimberley diamond mine was already open and a huge swathe of gold ore had been discovered in the Boer-controlled state of Transvaal. The war started badly for Britain as the well-armed, fleet-of-foot Boer commandos outmanoeuvred the conventional military approach of the British generals. News came of the sieges at Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley.

Then a wave of jingoistic, patriotic fervour was whipped up by the Press and over 180,000 men were recruited to add to the existing British army in South Africa creating an “Expeditionary Force” whose sheer weight of numbers would eventually prevail ….. but at a cost as we’ll see later. The war was brought home to villages, towns, cities across Britain, and Teignmouth was no exception.

Sidney Charles Wills, together with his friend William James Buckingham and another lad, George Matthews, from Shaldon were the three local volunteers who took that journey to South Africa. But they didn’t leave quietly. In what was probably not atypical of thousands of places across the country these three young men received a civic send-off and procession through the streets.

The Send-Off

A shortened extract from the Teignmouth Post of 13th April described the departure of troopers Buckingham and Mills:

OFF TO THE FRONT! A GENUINE AND HEARTY SEND OFF.

Teignmothians gave themselves away on Thursday evening. It was not a carnival, but just a few thousand people revelling in excitement to give a hearty send off to a couple of young patriots “going to Table Bay.” Like many a public demonstration we could mention, the whole thing was got up on the spur of the moment, and as a natural consequence in Teignmouth, this impromptu “Good-bye” was an unqualified success—not lasting an hour, but making a deep impression on the minds of the rising generation, who will not readily forget the scene at the railway station and the crush of people to cheer and wish “God speed” to Troopers W. Buckingham and Sid Wills, who have volunteered to go to the front in the ranks of the Rough Riders’ Corps.

Buckingham was a telegraphist and clerk at the Post Office. His father was for many years Chief Officer of Coastguards at Teignmouth station. Wills is the youngest son of the late Mr. Joe Wills, and as the families of the two young fellows were so well known in the town, it was considered – and wisely too – that we should not let them go away without some reminder that their desire to do their duty as soldiers was admired and recognised by the townsfolk generally.

And it was a ‘send off’! No generals could have wished for or received such an ovation. Cheers, music, and miniature guns rent the air, and for forty minutes a throng of people occupied the streets, escorting in procession the two young “gentlemen in Kharki going South.” It was an unexpected demonstration and proved how well we can do the thing when our hearts are in that direction.

Previous to the formation of the procession, there was an interesting and pleasing ceremony performed at the Post Office. The staff had a desire to mark their appreciation of Buckingham’s companionship and to assure him that during the time he was working with them, his good tempered and friendly character had not escaped notice, and the whole body of postal workers were at one in putting together for a reminder of happy days in the Teignmouth office of the G.P.O. So they got him a purse and placed something in it bearing the profile of Her Most Gracious Majesty as one memento; and from Mappin and Webb’s they obtained a most useful and necessary present, in the shape of a soldier’s combination knife in case and with lanyard .….. Mr John Berry handed the young trooper a pocket Bible; and with cheers and a verse of the National Anthem the initial proceedings closed.

A move was made for the Rifle Drill Hall. Here the I Company of the 1st R.V. had assembled, and to their credit be it said, as well as to the Artillery Volunteers, the men responded to the bugle call at what may be termed a minute’s notice. Armourer-Sergt. Tapper was on duty and Color-Sergt. H. Hooper commanded. The hall was crowded. Color-Sergt. Hooper addressing Buckingham as one of their comrades, said he had wired Captain Beal for permission for the Company to turn out that evening, and the Captain had wired “Yes, with hearty congratulations to Buckingham, and wishing him a safe voyage, God-speed and a safe return.”

He (Sergt. Hooper) said he supposed he must address their comrade as “trooper” now, but he could assure him that every member of I Company thoroughly appreciated what he had done. During his connection with the Company he had been an obedient and steady soldier, and if he made as good a trooper as he had been an infantry man he would be certain to come out all right. They were sorry to lose him, but as a soldier he preferred to go on active duty at the front, and they thought the more of him for the step he had taken. The few articles which he handed him, on behalf of the Company, would be useful and necessary to him in the undertaking he had entered upon and would no doubt remind him of the pleasant time he had spent in the ranks of I Company.

Color. Sergt. Hooper then handed Trooper Buckingham a silver mounted pipe and pouch of tobacco; a box of cigars given by Mr. H. A. McBryde ; a box of cigarettes from Mr. J. Steer, and a Tam O’Shanter hat from Mrs. Bell-Soames, to which was attached the following good wishes “God bless you and all true patriots and grant you a safe return.” (Applause.)

A presentation on behalf of the Company was made to Trooper Wills in the shape of a pipe and pouch, and a box of cigarettes and holder from Mr. George Hill, together with a Tam O’Shanter cap with the same lines attached as on Trooper Buckingham’s. In thanking the members of I Company and the friends who had been so kind Trooper Buckingham said that what he had learnt as a Volunteer had already proved most useful to him, and he would not be afraid to stand before many of the regulars he had met with since be had joined the ranks as a trooper. (Applause.)

Headed by the Artillery Band. the Artillery Volunteers, under Lieut. D. V. Whiteway-Wilkinson, and the Rifle Volunteers, made up a procession in Northumberland Place and at once proceeded to the station to catch the up-mail. At McBryde’s London Hotel colored lights were displayed, and a salvo of cracker guns was fired. The excitement was at its highest, and the two young troopers were given their “baptism of fire ” in the way of volleys of “Celestial Empire” pyrotechnics. Along the Station Road Mr. Croydon had arranged a deafening bombardment. A salute of no less than 150 “guns” being fired in four minutes. This banging, together with the inspiriting tune “The Soldiers of the Queen.” and the cheering of a thousand and more people, was a scene, such as has never been witnessed in Teignmouth before, whilst the crush at the station doors was something tremendous. There was a general waving of hats and shaking of hands, and the send-off was completed when the train steamed out of the station.

Before the two young men left the platform. Mr. S. A. Croydon presented each with a box of cigars. Bandmaster McDermott gave the signal and the band struck up that dear old Scotch air ” Auld acquaintance.” A few more ringing cheers and then a verse (vocal and musical) of “God save the Queen.”

Reading between the lines of this article you might speculate that it was Sid’s friend who led this venture and that Sid had been persuaded, cajoled, goaded into joining him. Despite the patriotic fervour that was sweeping the country there might also have been a sense of adventure for young men of their age (Sidney was 18 at the time). There is also a slight clue in the article in how this might have been presented to young men when it refers to them as joining the ranks of the “Rough Riders’ Corps”.

This was officially the Imperial Yeomanry, created by Royal Charter in December 1899 specifically to support the regular army in South Africa following the disastrous series of defeats they had experienced earlier that month. Informally they were known as the Rough Riders (or simply the ‘Roughs’), named after Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders who served in the Spanish-American war of the previous year. Sid and his friend were both in the 79th Company of that Imperial Yeomanry.

Men joined up for only one year. They were organised into county service companies and equipped as “mounted infantry”. They received minimal training before all being shipped out straight into the fray in April 1900. Adventure?

Some brief news of Sid and William appeared in the Teignmouth Post and Gazette of 27th April:

EN VOYAGE

Mr J U valentine has received a few lines from Trooper Buckingham, written at sea on board the transport SS Canada. He says that neither Sid Wills or himself have been sea sick, though scores of the others have been. They expected to call at Las Palmas, and he should post the letter to Mr Valentine from that port of call. They were, he said, a bit cramped on board, otherwise very comfortable and good grub. The ‘send off’ quite surprised him for Teignmouth.

Three months later more news arrived home from Trooper W Buckingham in a letter to his friend Bert Valentine which was reproduced in the Teignmouth Post and Gazette of 31st August:

Pretoria, July 31st 1909

Dear Old Chum,

We arrived here from an expedition against Botha yesterday and received two English mails. Last Monday fortnight (16th) we left here after Botha and were under artillery and pom-pom fire before noon, but he was playing a retiring fight as we attacked a kopje one side the Boers retired the other. Five of our company are missing and our transport waggon, supposed to have been taken prisoners, and one of ours had his horse shot under him. You see my great wish to be under fire has been realised, it is very funny to lay behind boulders on a kopje and hear the shells going over your head, they sound like running water. After our waggon was captured we were put on quarter rations, vis: 1½ biscuits and about ½ pint of coffee per day. We have not slept under canvas for a month. It is cold at night and very hot by day. We march about 18 to 20 miles a day and start before daybreak, often not camping until after dark. Our horses are done up and every man will be heartily glad when the war is over. We are in Ian Hamilton’s column but “Bobs” was with us several days. It is astonishing to see how our gunners can put shells into the Boer trenches with the howitsers.

Well, dear old chum I must close now, will tell you all about this outing when I come back, if spared. Give my kind regards to all at home, and the dear old boys.

Your ever sincere “pal”, “Buckie”

P.S. We are off after another body of Boers at daybreak tomorrow, we expect more fighting.

The Return

The Teignmouth Post and Gazette produced a souvenir programme with photos of Troopers Wills and Buckingham on the front (it would be wonderful to see a copy if one still exists). The troopers were arriving home on the mail steamer Roslin Castle expected at Southampton on 8th July and plans were made accordingly. A committee was formed, money was raised, expectations were raised but in the event there had to be last-minute changes since Sid Wills had been detained in hospital and would be returning on the following ship. The committee decided to go ahead with two welcomes, the first a more abbreviated event and the second when Sid Wills arrived which would be the fuller event originally planned.

Troopers Sid Wills and George Matthews arrived back in Southampton on 18th July in the Manchester Merchant.

The full celebratory welcome home for all three troopers then took place on Wednesday 24th July. The Teignmouth Post and Gazette of 26th July covered it in full. Here is an abridged version:

RETURN OF TROOPER WILLS. A PRESENTATION, SERVICE, SUPPER AND CONCERT.

The welcome extended Trooper Sid Wills on his home-coming on Wednesday evening was none the less demonstrative and hearty as that accorded his comrade Trooper W. Buckingham when he came home. The procession, which consisted of an escort of Yeomanry preceded the three Troopers on horseback and in their uniforms of kharki and slouched hats. The band of the Volunteer Artillery was in front, playing “Soldiers of the Queen.” The Volunteer and the Rifle Volunteers followed. There was a plentiful display of bunting in the town. The bells in the tower of St. Michael’s rang out and the thousands of people who watched the procession cheered to the echo. At the Den the commander of the volunteers, approached the platform, and introduced Trooper Wills.

PRESENTATION:

Capt. W. H. Whiteway-Wilkinson said: I offer you, Trooper Wills, sincere congratulations on your return from the front. (Cheers).

On behalf of the Town of Teignmouth I extend you a most hearty welcome back to your home. We were all sorry to hear that you had been delayed in hospital at De Aar, and we were delighted to hear that you were able to leave by the next ship. We should much liked to have seen you here with Trooper Buckingham, but though delays are dangerous you are here now safe over your journey. (Cheers).

When you were in Africa, you no doubt heard the strains and words of a song by the name of “Soldiers of the Queen.” When you left Teignmouth to take part in the struggle in the Transvaal you were a soldier of the Queen. Certain lines of that familiar song refer to the men who have been and the men who have seen. You have seen what it is quite likely you may never see again in your lifetime. You have done what many of us have never done. You have seen the grouping of the units of the magnificent fighting forces of this Empire (loud cheers)—and you left this country as one of these units, and every branch of the fighting forces of this country, together with its Colonies, were represented, and with these you have mixed, been one of them. Although a soldier may not be in the fighting line, or in actual engagements, he did his duty if he offered his services and went to be ready when needed. (Hear, hear.) The soldier, as long as he behaved himself, was worthy the respect of every citizen. There used to be an old song with the troops in India, and he believed the words were:

“In this campaign

There’s no whisky or champagne

But we can teach them

How to respect the British soldier.“

You have, since you left home, been in peril by sea, and open to the dangers of being killed or wounded, or being caught by disease. The last mentioned fact you accomplished, but fortunately for you, thank God, you have recovered from the latter, and we trust you will be none the worse for it.

It gives me pleasure to offer you hearty congratulations on your safe return and to express that feeling on behalf of your townspeople. It was the grim business of some of the units to take up arms as regular soldiers, whilst there were a lot in business occupations who did not mind taking up arms for the mere love of their country, and they had proved themselves worthy soldiers. (Hear, hear.) It must be a source of gratification and comfort to the soldiers to know they were not forgotten, to realise that all at home were ever mindful of the welfare of the soldier when away. Scarcely a week passed without something having been sent out to South Africa, to let the British soldier know that although he may be a thousand miles away, those at home did not forget comforts of some sort, and the chocolate boxes, plum puddings, and many necessaries sent out, were to let the soldiers know they were ever in the hearts of those at home.

I am asked by the Committee to hand you this watch, subscribed by your fellow townspeople in appreciation of your services in South Africa. It will be some little token to remind you of what you have done, that you did your duty as a soldier and a man. (Cheers.) When you look at the watch I now hand you, and the inscription inside, you will be able in years to come, to say, “thank God, when my country was in distress, I gave my services and did my duty as a citizen soldier should do, and by this present I am aware that my fellow townspeople appreciated what I did”. With the watch, we one and all wish you long life and happiness to wear it, so that you may have some pleasure after what you have been through. (Loud and prolonged cheers).

Trooper Wills regretted that he was unable to have been present with his comrade Trooper Buckingham, but that could not be helped. He was glad to say he felt in the best of health, but he could hardly find words to express his thanks for the hearty welcome and the handsome present given him. He should always look upon it with pleasant recollections, and a mark of the kindness of the townspeople of Teignmouth. He wished to thank everyone and that was about all he could do.

The watch presented was engraved on the outside with Trooper Sid Wills’ monogram, and inside is the following inscription: “Presented to Trooper Sid Wills, 79th Co., I.Y. by the inhabitants of Teignmouth on his return from the South African Campaign, July, 1901.”

There followed a Thanksgiving Service at St Michael’s Church taken by the Rev. J. Veysey.

THE SUPPER AND CONCERT:

At 8.30 a goodly company assembled at the Town Hall and sat down to a capital supper provided by Mr. W. H. Bonner, chef of the Regent Street Restaurant.

This was followed by toasts and the concert which “was thoroughly enjoyed, as a good deal of the professional element was introduced, whilst the local talent embraced many of the best vocalists and musicians in Teignmouth, each of whom were heard to advantage. The programme included a popular song of the time: “When the Boys in Kharki all come home.”

The following day the three Troopers called on Mr. S. A. Croydon (hon. secretary of the Reception Committee), and asked him to convey to the public their thanks for the splendid reception given them. They also highly appreciated the efforts of the Committee for what they had done and wished to express their thanks to one and all for their great kindness.

Aftermath

The Country

By the time the three troopers had returned to Teignmouth the feeling in Britain was that the war was all but over. Kimberley, Ladysmith and Mafeking had been relieved, the Boer state capitals of Pretoria and Bloemfontein had been captured and Botha’s commandos had been driven back. But the war continued for almost another year as the Boer tactics of guerrilla warfare continued to have an impact. Eventually sheer weight of numbers prevailed (Britain deployed over half-a-million armed forces against approximately 60,000 Boer commandos) and the surrender treaty was signed in May 1902.

Britain may have won the war but at what cost? Financially the war cost around £20 billion in today’s terms. In terms of casualties, an estimated quarter of the total British force were either killed, wounded or returned home sick or wounded.

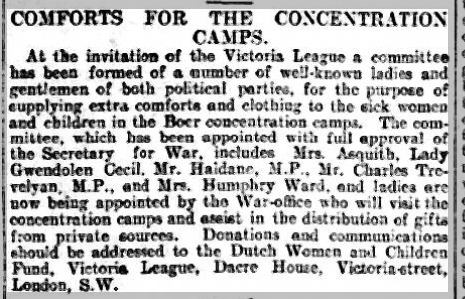

In human terms Britain descended to a low in warfare. Unable to win through conventional means the generals adopted “scorched-earth” policies and introduced “concentration camps” for Boer women and children and Africans. Over 50,000 died in those concentration camps.

It is ironic that in the very same edition of the Western Morning News, directly above the announcement of the arrival of the three troopers back to Teignmouth, there appeared the following article:

Perhaps this was coincidence or perhaps the paper was trying to reflect the shifting attitude in the country to the war. The fact that this effort was sanctioned by the Secretary of War suggests that there was a definite feeling of shame, guilt, vulnerability in the government. Whatever the interpretation, the whole debacle brought about the fall of the British government at the election in 1903.

Trooper Buckingham

Sid’s friend “Buckie” returned to his job in the post office and appears to have simply settled down to a normal life and put the war behind him. He was an active member of the Corinthian sailing club and the Teignmouth Volunteers Rifle Club up until the outbreak of WW1 when he joined the Wessex Signal Company stationed in Torquay. After that war he remained with the post office until at least 1936 when he was acting Postmaster. Presumably in his retirement, he became an active member and honorary secretary of the Winterbourne Bowls Club. He died in 1963.

Trooper Wills

After his triumphant return from the South African War Sidney seems to have been more influenced by his experiences there than his friend. This ultimately led to the tragedy which forms the second half of this story.

From Triumph to Tragedy

By way of background, Sidney grew up at the Devon Arms Hotel, 48 Northumberland Place, where his father Joseph was the proprietor. This experience subsequently formed a grounding and a backdrop to his future life. At the time of the 1891 census he was the youngest of five children with three sisters – Kate, Amelia and Florence – and one much older brother, Albert. His father died five years later when Sidney was 15 and, by then, three of his siblings were well into adulthood so his mother would have been left looking after just him and his sister Florence.

So ….. what happened after the war?

Despite his harrowing introduction to the country Sidney seems to have been attracted back to South Africa, lured probably by the potential pickings to be made from the gold mines of the Transvaal. He returned there probably after the end of the war in 1902 and it looks as though he stayed for 2-3 years “engaged in mining” (Teignmouth Post and Gazette 10th Jan 2013).

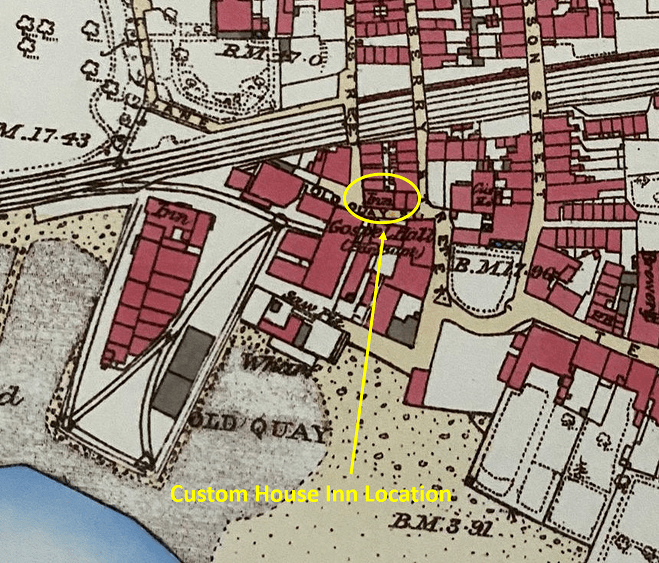

He was back in Teignmouth by May 1905 when he took on the licence of the Custom House Inn, 9 Old Quay Street Teignmouth. This had become available through the death of the previous proprietor, Mr George Berry, in November 1904. Sidney was now following in his father’s footsteps as a licensed victualler. The Teignmouth Post and Gazette of 19th May commented “The best of good wishes are being extended to Mr. Wills from all quarters. He takes possession on the 1st July.”

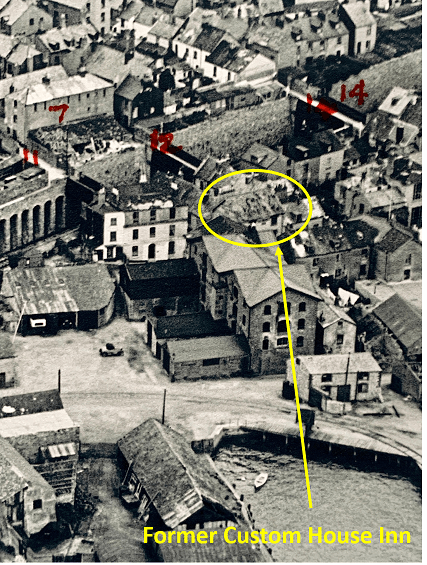

The Custom House Inn was a very different establishment from the probably more salubrious Devon Arms Hotel where Sidney had grown up, so Sidney may have faced a bit of a baptism by fire. It was in the docklands area, the heart of the working quarters of many in Teignmouth. Like so many pubs in Teignmouth it has long since disappeared. The building still exists though, having being bought by the Rotary in 1937 and converted into a special residence, Eventide House, for Old Age Pensioners. It features on the 1890 Ordnance Survey map and in a rare aerial photograph from the 1930s (Viv Wilson archive). Ironically in 1907 it stood opposite the Teignmouth Rifle Club rifle range (now used for indoor bowls).

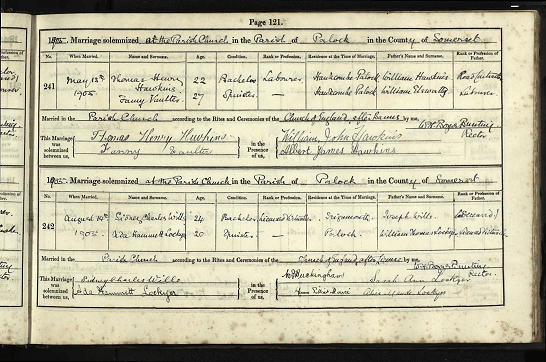

Then a few months later, on August 14th 1905, Sidney married Ada Hammett Lockyer. At the time she lived in Porlock, Somerset, where her parents ran the Castle Hotel. You do wonder how they met. Was it a chance whirlwind romance in the short time since he had been back from South Africa? Or had he known Ada from his earlier days, remained in contact and returned to marry her?

Ada’s earlier background was similar to Sidney’s. Born in Mamhead in 1886 Ada is shown in the 1891 census as one of six daughters to (William) Thomas Lockyer and his wife Rachel. Her father had been a head gamekeeper in Plympton St Mary but her parents subsequently moved and ran the “popular” Castle Inn in Holcombe. They were still there in 1901 but then moved to Porlock where her parents had taken over the Castle Hotel and later went on to run the Exeter Inn in Dawlish.

The wedding was “an altogether pretty though quiet one. The bride was attired in a gown of French grey colienne trimmed with white silk, and white chiffon hat to match ….. the happy couple, amid a shower of rice and confetti from their friends and a large number of villagers who had assembled to bid God-speed, drove to Minehead en route for Weston-super-Mare, where the honeymoon is being spent.”

Whether five years at the Custom House Inn had taken its toll or Sidney felt that a better life could be had in South Africa it seems that he returned there, initially on his own, probably late 1910 or early 1911. The 1911 census showed Ada living on her own at 5 First Avenue, Coombe Vale, with their three children – Sidney Thomas (4), Joseph Verdon (3) and Ernest Charles (8 months, born July 15th 1910).

In September 1912 Ada and her sons sailed out to South Africa to join Sidney, seemingly to start a new life there but finding tragedy instead.

Tragedy Struck

The Teignmouth Post and Gazette of 10th January 1913 described the full story:

SHOCKING TRAGEDY IN SOUTH AFRICA.

TEIGNMOUTH CONNECTION

HUSBAND’S TERRIBLE DISCOVERY IN HIS HOME.

On December 20th a paragraph appeared in The Teignmouth Post to the effect that news had been received in the town of the death at Benoni Brakpan, Transvaal, of Mrs Ada Hammett Wills, wife of Mr Sidney Charles Wills ….. It was freely stated, and the majority of people were at the time under the impression that the cause of death was blood poisoning, and it was not until the last few days, that the full circumstances of the terrible tragedy became known in England.

On the 7th of September last, Mrs. Wills sailed from Southampton with her three little boys to join her husband in South Africa where he is engaged in mining. They arrived safely, and until the 12th of last month lived in the land of their adoption. Then occurred a tragedy which has cast a heavy shadow over the household, depriving the husband of both his wife and a friend. Returning home late at night he found his wife lying dead, while his friend, a miner named Roberts, who also resided in the house was in a dying condition with a revolver beside him. The sad affair which is, so far, owing to the entire absence of witnesses, shrouded in mystery, is reported to be one of the most terrible recorded is the annals of crime on the East Rand.

The deepest sympathy will go out to the family at Dawlish, and also to the husband and children in South Africa, and to Mr. Wills’s two married sisters who reside in Teignmouth—Mrs. S. Furler, of Fore Street, and Mrs. G. H. Furler, of 8, Hermosa Terrace. He has also several cousins in the town.

The reports published in the “Rand Daily Mail “(Johannesburg) and “Benoni Advertiser”, both dated December 14th, differ slightly as to details. From what can be gathered between the two stories, the shocking tragedy occurred between 11pm and midnight, on Thursday, the 12th December in Lake Avenue, Benoni.

Somewhere about 6pm Mr. Wills left his home at 39a Lake Avenue, to compete in the air rifle Bisley at Johannesburg, his young wife seeing him off. He returned by a late train, and, procuring his bicycle at the station, proceeded to his home, which he reached shortly after midnight. Entering the passage, he wheeled his machine to the accustomed spot, and noticed that the dining-room light was burning. As he passed the dining-room, which door was partly open, he saw Dave Roberts, who was a friend of his, and rented a room in the house, lying on the floor breathing heavily. As Roberts had, it appears, been drinking excessively of late, and had recently lost his job at the Brakpan G.M., where he had been employed as a miner, the Teignmothian came to the conclusion that his friend was lying helplessly drunk.

A minute or two later he returned to the dining-room with the object of getting Roberts to his own bedroom. He then noticed the booted feet of a woman projecting beyond the door and on looking behind was horrified to find that his wife lay stretched on the floor, and weltering in a pool of blood, her face being almost blown away. He then turned round and saw that Roberts was also lying in a pool of blood, which was oozing from the right side of his head. By his side lay a Browning pistol. Rallying from the shock the horror-stricken husband rushed into an adjoining bedroom, occupied by his three little sons aged 6, 4. and 3 years respectively. The two younger ones were asleep, but the eldest was sitting up in his bed, and in a scared voice the poor little fellow said: “I am so glad you have come home, Daddy, l am so frightened. There was such a big bang just now.” The half-demented father pacified the little boy for a few moments and then hurried out into the street to call the police.

A detective and a sub-inspector were quickly on the scene, and Drs Smith and Stevenson were also summoned and pronounced life to be extinct in the case of Mrs Wills. There were two bullet wounds in the temple. Roberts was still alive but unconscious, and he was taken to the cottage hospital where, however, he died about an hour later. It was seen from the first that his condition was hopeless. There were no signs or indications of a struggle having taken place in the room. The body of Mrs. Wills was removed to the Bloemfontein mortuary. Two bullets had entered close to each other on the left side of the face, and the scorched appearance of the skin showed that one at least had been fired at very close range. Roberts was shot through the right side of the head.

One of the papers states that Mr Wills cannot suggest a possible or probable reason for the crime, and they go on to state, “Various conjectures are rife, but the most likely one is that the deceased woman spoke to Roberts about his intemperate habits and asserted that he was out of work in consequence of this. In a fit of rage, Roberts, it is assumed, drew the pistol from his pocket, fired twice at the unfortunate woman, and then turned the weapon upon himself.” Another paper states: “Yesterday (11th December) in a local hotel, he (Roberts) exhibited a small Browning pistol, and used the words, “l am fed up this. Two souls shall go aloft to-night.” Roberts, whose only relative in South Africa is a brother, resident in Johannesburg, had been mining since 1907. Prior to that he was employed at Longs Hotel and the Victoria Hotel, Johannesburg, as a barman. He was 35 years of age, and had borne a good character.

It is stated that Mr. and Mrs. Wills had just fixed up their new home, and Roberts lived with them as a friend. The greatest sympathy Is felt for all concerned. At present the three little boys are in the hands of friends and are oblivious of their tragic bereavement. Mr. Wills is, naturally, overwhelmed with grief at the terrible occurrence. The result of the inquest has not yet reached England.

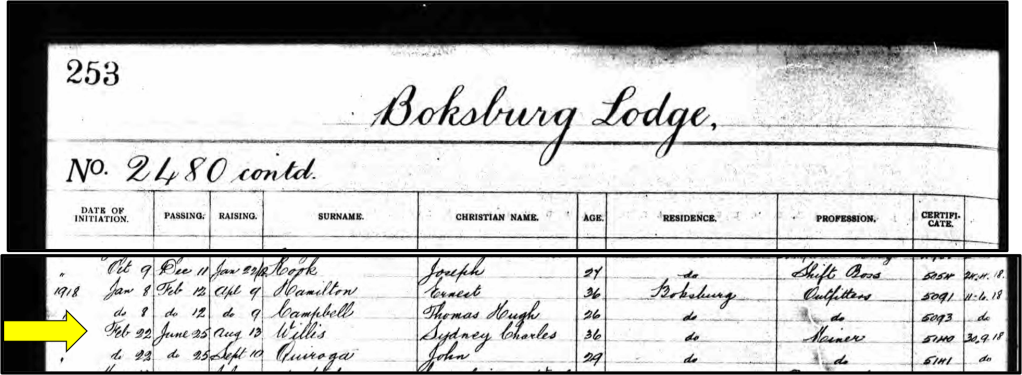

It seems that Sidney and his three sons remained in South Africa after this dreadful incident and he continued working as a miner. At some point he appears to have re-married and he and his new wife, Elizabeth Turner Wills, had a son, Norman, around about 1919. He joined the Boksburg Lodge of Freemasons on February 22nd 1918 and, according to their register, he was recorded as a miner and remained a member there until July 1920.

At some point within the next twelve months or so he, with his wife and family, returned to Teignmouth. His freemasonry membership transferred to the Teignmouth Benevolent Lodge of Freemasons on November 11th 1921 where he was now registered as a “hotel proprietor” (believed to be the New Quay Hotel). His mother, Elizabeth Newkey Wills, died on 2nd July 1924 and was interred alongside her husband in Teignmouth Old Cemetery.

In 1925 Sidney’s life came full circle. The licensees of the Devon Arms Hotel, Mr and Mrs Longthorpe, separated after a dramatic court case in which Mr Longthorpe was accused of assault and persistent cruelty to his wife. Sidney was quick to seize the opportunity and acquired the licence for the Devon Arms at the Newton Abbot licensing session on Tuesday 3rd March 1925. The award of the licence was accompanied by a strange comment though, as described by the Western Times of 6th March:

“Major Halford Thompson, Deputy Chief Constable, said he offered no objection to the transfer, provided Mr Wills agreed to terms which he (the Deputy Chief Constable) did not wish to make public, but which he would hand to the bench. Mr Wills indicated that he would agree to the terms, and the Bench granted the application, subject to an inquiry from Liverpool regarding the testimonials being satisfactory.”

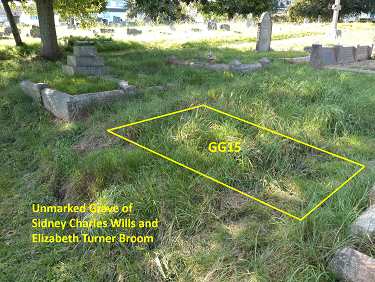

His tenure at the Devon Arms Hotel did not last long. Sidney died three years later, aged only 47, on Tuesday 31st January 1928. His funeral took place at the cemetery the following Saturday and was “largely attended”. Surprisingly, he too was buried in an unmarked grave, simply plot GG15. He was joined six years later by his second wife who had re-married and was then Elizabeth Turner Broom.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Rosemary Booth, Gwynneth Chubb, Jemima Eastwood, Chris Inch, and Viv Wilson MBE for their assistance in resolving the mystery of the Custom House Inn

Sources and References

Extracts from contemporary newspapers are referenced directly in the text and are derived from British Newspaper Archives.

Ancestry.com for genealogy, including Freemasonry records

Wikipedia for general background information. Other sources, with hyperlinks as appropriate, are as follows:

- Fabulous Polyphon recording of music of “When the Boys in Khaki all come Home“

- Photo of De-Aar hospital

- Guardian article – reference to known casualties

- Magnolia Box – Transvaal Gold Fields

- Tyne built ships – Manchester Merchant 1900

Ada Hammett Wills was my great Aunt. My grandmother was her sister Beatrice Mary Lockyer. It was very interesting to find out about Sidney Wills as I knew nothing about him.

LikeLike

It’s amazing the connections that emerge when you start researching people in the cemetery.

LikeLike