The inquest was opened on Saturday evening by the District Coroner (Mr. S. Hacker) at the London Hotel. Superintendent Moore was present on behalf of the police. Mr. R. Hall Jordan attended as Clerk to the Urban District Council, and the owner of the engine, Mr. R. C. Fenton, was in attendance, accompanied by Mr. I. Carter, solicitor, Torquay. Mr G. H. Jarvis, member of the Urban District Council, was chosen foreman of the Jury.

At the suggestion of Mr Hamlin, a juryman, all the witnesses (except Mr Fenton) of the occurrence were ordered to remain outside the Court until they were called. Mr Fenton being the owner of the engine was allowed to remain.

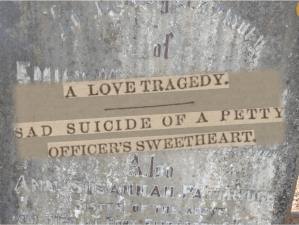

Mr. J. T. Waite, Sergt.-Instructor of Volunteers, identified the body as that of his child, Frances Maud, who was seven years of age.

Evidence from the owner, Mr Fenton

Mr. R. C. Fenton, C.C., Maidencombe, said he owned two traction engines. On Friday one of them was on its way from Torquay to Dawlish drawing three trucks of bricks, and he joined it at Kingsteignton. His man, Wm Maffey was in charge of the engine, which was also accompanied by three other men, the regulation number, named Samuel and William Hannaford and Passmore. The trucks contained about 9000 or 10,000 bricks, and they averaged 2½ ton per thousand. The load, therefore, amounted to about 25 tons, added to which was the weight the trucks, making in all about 30 tons behind the engine. No difficulty was experienced on the way from Kingsteignton.

The driving wheel of the engine was seven feet in diameter. The engine which was about two years old, had just been to Rochester where it had been thoroughly overhauled by the makers, Messrs Aveling and Porter. It was 42 horse power, and around London the ordinary load for such an engine was about forty tons. Witness was not aware that under the Act of 1861 the load for each truck was limited to eight tons. The tyres of his trucks were about nine inches wide, and they were provided with diagonal cross bars to enable them to grip the road.

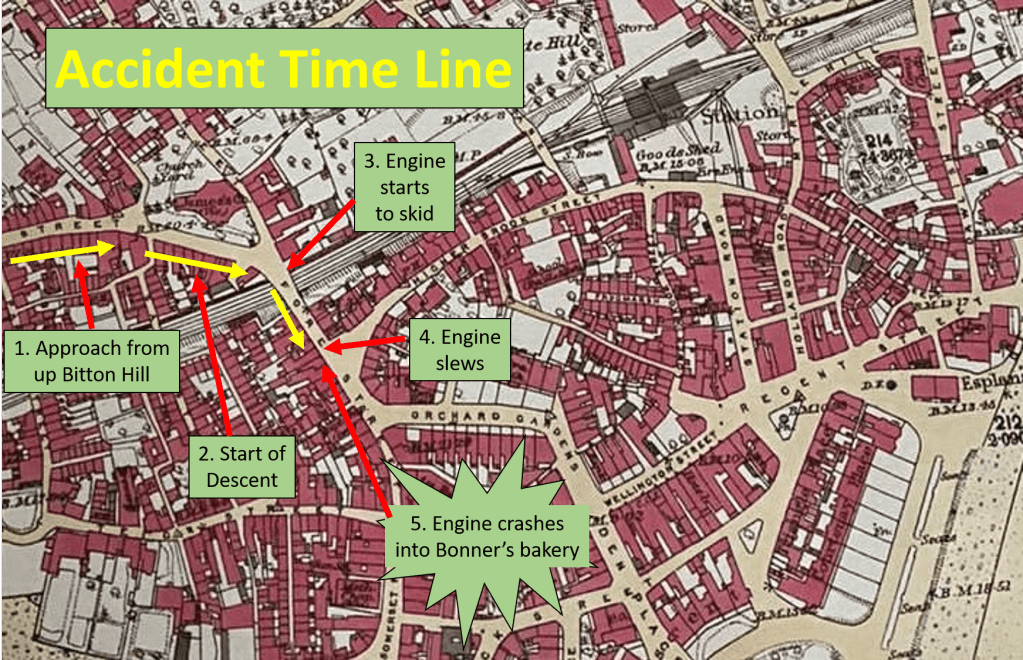

The engine took the load without difficulty up and down the hills until Bitton-Hill near Teignmouth was reached. There, in consequence of the wheels slipping on the stones, one of the trucks had to be dropped halfway up. Witness got off at this point, and the driver first took two trucks to the top, and then returned for the third one which was kept stationary in the mean time by blocks of wood and the drag on the wheel.

The Coroner asked whether it was not a dangerous practice to leave a truck in the middle of a steep hill like that. Witness said he had never found it dangerous. Of course the engine was never disconnected until the driver had made quite sure that the truck was safely fixed.

Proceeding with his evidence, witness said that on the top of Bitton Hill he again rejoined the engine and took charge of the steering. He proceeded without stopping.

The Coroner: Don’t you think it would be a prudent thing to stop at the brow of a hill? Witness: No, there would be no object. The Coroner: But you would lose the impetus would you not? Witness explained that there were two speeds to the engine and it was the usual practice to stop it before proceeding down a hill and alter the machine from the fast to the slow gearing. That was done in the present case.

In answer to the Foreman, witness said that on ascending Bitton Hill something went wrong with the injector, but that did not affect the control of the engine

In answer to a juryman, witness said he had not noticed that some spokes in the wheel by which the brake was worked were defective.

Continuing, Witness said the road in question was much barrelled. On coming down the engine commenced to skid, and the driver took the steering gear. Witness attributed the skidding to the smooth state of the stones on the road. He had been told that the rain had swept away the earth and left a stone surface. Thus, the engine wheels were unable to obtain a grip. At the spot where the accident happened the engine suddenly “slewed round” at right angles to the road. He was thrown from his seat, and for a few moments he was jammed. He quite expected the engine to topple over on its side. Naturally, he was a bit confused. When he looked round he saw that the front truck had smashed into a shop. He did not know that the child was there until his attention was called to it by some bystanders. The engine was not quite touching the footpath, and the extreme bar behind was not touching the wall of the house. How the child got there he did not know. She was apparently killed by the draw bar of the engine.

The Coroner: To what do you attribute the occurrence? Witness said in his opinion it was owing to the fact that the road was barrelled to a height in excess of what was required. Road engineers as a rule, in a 30 feet road, made it six inches higher in the centre than by the side- but this road would exceed that – more than doubIe, perhaps three times as much. Consequently, the engine, if a little bit on one side, would have a tendency to slip along on one side. If the road was level, it would have slipped down straight, there would be no reason why it should go sideways. The Teignmouth Surveyor had told him that it was a slippery sort of stone.

The Coroner: Then you do not say anything about the weight behind the engine? Witness: No; I don’t think it was an extraordinary weight for an engine of that class.

Mr Hamlin (a juryman) suggested that if the road was so high in the centre it would have a tendency to prevent the engine from slipping to one side. Witness said that was a nice point. It might be the result if the centre of the road came directly under the centre the engine.

The Coroner: You do not attribute the accident in any way to the trucks? Witness said he thought a sufficient answer to that was they had come the whole way from Newton, and passed down hills much steeper in perfect safety. The Teignmouth Surveyor had told him that he had himself had trouble on the hill with the town roller. Witness’s opinion was that the engine would have slipped if there had been no weight behind. He had ridden it on a bicycle.

The Clerk to the Urban Council (Mr Jordan) asked whether the act of reversing the gear and stopping the wheels with 25 tons behind would not necessarily cause the engine to skid. —Witness replied that was a difficult matter to say. He thought it would be found that the driver did not reverse the gear until he found the engine absolutely skidding.

Evidence of William Maffey, the driver

Wm. Maffey, the driver, was next called. He was told by the Coroner that he was not obliged to give evidence, but he could do so if he pleased. Witness elected to make a statement.

He said the Board of Trade did not grant certificates to traction engine drivers. He corroborated a large portion of the previous witness’s evidence, and added that on coming to the hill in Fore-street Mr Fenton gave signs to the men to put on the brake. When that was done, the engine was proceeding at the rate of from a mile or mile and half an hour He explained that it was impossible to stop the engine to put on the brakes. If they did it would probably be unable to restart, or if they did start again with the brakes on the machinery would be greatly damaged and the brake gear would be rendered useless.

The engine commenced to skid, and gathered speed as it proceeded. He absolutely lost control of it. It was impossible to steer, and the engine went where it liked. The back of the engine struck the wall by the side of the shop, and the first truck ran against the side of the engine and the shop window. Witness did not know the child was there. He had a mishap at St. Mary Church about a fortnight ago when, consequence of the road having just been watered, the engine skidded and knocked down a doorway entrance to a garden.

Answering further questions, witness said the roads about the district, especially at Torquay, were very slippery owing to their smoothness. Macadamized roads were more dangerous than ordinary country roads. There had been an accident with an engine at Totnes, but it was not their engine.

At this point the inquest was adjourned to be resumed the following day.

Maffey, recalled, said that it was just before he reached the bridge when he put the brake fully on. It was put on gradually. If it was put on tight at first the engine would be stopped. The engine was three or four yards past the bridge when it commenced to slide sideways.

Answering Mr. Hutchings, witness said he shut off steam two minutes before he applied the brake. He had been traction engine driver all his lifetime, but he had never been told how much weight was allowed to be carried.

Evidence of Employees

Samuel Hannaford, an employee of Mr Fenton stated that he was in charge of the trucks. On ascending Bitton-hill the wheels of the trucks slipped round. This often happened. As Mr Fenton thought it was “pretty much of a load”, he had one truck detached and took up two. The engine subsequently returned for the other truck. At the top, while proceeding again with the three trucks, Mr Fenton motioned for the brakes to be applied. Witness put them on the first two trucks, and a man named Passmore applied the brake to the third. They had to go between the trucks to do this. It was all done before the engine commenced to descend the hill. On turning the corner, his notice was attracted to the wheels skidding. He then turned round and said to his mate, Passmore, “Look out, you had better keep away a little, I believe she is going to run away.” He could not say positively that the brake of the engine was on, but the wheels were certainly not revolving. These, he thought, must have been stopped by a reversal of the driving gear. It was not often that the brake alone would stop the wheels of the engine; although he had stopped truck wheels in that way. On reaching the spot opposite Higher Brook-street, the engine suddenly slewed round.

The Coroner: What caused the engine to slew in that way —Witness said he thought the driver must have locked it a little order to get it to the other side.

Replying to further questions from Mr Hutchings, witness said Fore Street-hill had been rendered greasy by having apparently been recently watered in the ordinary manner. The road was not really wet.

If the road had not been recently watered you think the engine would have slipped —No, I don’t believe she would have slipped. If the road had not been watered and if the surface of the road had been rough, the engine, I think, would have gone down all right.

Wm. Passmore, an employee of Mr Fenton gave evidence of a similar character. He also attributed the accident to the slippery state of the road, but he did not notice that it had been recently watered. Every possible precaution was taken.

Evidence was also given by Wm. Hannaford, St. Marychurch, who said that his duty was to walk in front of the engine. When he came to the hill it did not occur to him that it was necessary to warn the driver to stop. He did not think it was so slippery as it turned out to be. The engine had descended hills quite as steep. When the skidding commenced, he ran forward to warn any vehicles that might be in the way.

Evidence from witnesses

Wm. Taylor, labourer, Bishopsteignton, stated that he saw the brakes of the trucks applied near the church gate in Fore-street. On crossing the bridge, the driver reversed the lever, and the engine at once commenced to skid. The road being “sideways” and the trucks being pressing heavily behind, the engine suddenly swerved round. If the road had been level it would probably have gone straight on.

William Edward Granger, house decorator, gave a description of the accident. He pulled away two children, and passed them back to his brother. He then went to the shop door and told Mrs Richards that nobody was hurt. At the same time he noticed someone behind the engine, and on passing round he saw the child jammed to the wall.

Thomas Wm. Jones, who assisted in rescuing the two children from their perilous position, said that when the engine turned, the trucks seemed to “take charge” of the back part. He had seen a good many engines pass down the hill, and most of them, notably Mr Hancock’s, stopped “dead”, at the brow of the hill and put on their brakes and chains.

Mr Hutchings : Then in your opinion the brakes were applied too late? —Witness: That is so.

Evidence from others

William Coram, foreman of the brickworks, where the trucks were loaded, stated that the three trucks contained altogether 25 tons bricks.

Mr Christopher Jones, Surveyor to the Urban Council, stated that the road between Bitton-Hill and the spot where the accident occurred was in excellent condition for all ordinary traffic. There was a rising up Bitton-hill of one in eleven, and from the top of Fore-street hill to the spot where the accident happened was a downward gradient of one in ten. He described Bitton-hill and Fore street hill as good macadamized roads in excellent condition. As they were chiefly used for carriages he aimed at making them as smooth as possible. Fore-street hill was not bevelled excessively. It was a 20ft roadway, and in the centre it was nine inches higher than it was the sides. Near the spot where the accident occurred it was a sideland road. The hill had not been watered on Friday. That, however, was done on Thursday. He examined it immediately after the accident and found it perfectly dry. Limestone was slippery when damp, but that was not used in metalling this particular hill. If an engine once slipped on the hill, it would never recover itself because the stone was so hard. He denied that he told Mr Fenton that his steam roller had skidded on descending this hill.

Answering further questions put by Mr Carter, witness admitted that the roads were watered by salt water. The metalling used was a green stone and it looked damp even when it was dry. His opinion was that the brakes of the engine were not put on soon enough.

In answer to Mr Jordan witness said there was nothing in the state of the road to cause the accident.

The CORONER put three questions to the jury.

(1) What was the cause of the occurrence which resulted in the death of the child;

(2) was that cause produced by neglect or a want of proper care and precautions in the working and management of the locomotive, or was it simply an accident which could not have been avoided by reasonable care and precautions; and

(3) if there was neglect or a want of proper care and precautions who were the persons responsible?

The crucial point was – What caused the wheels to skid? Was it an overpowering weight behind, the smoothness of the road, or that the brakes were not put on soon enough? Also, it was for them to consider whether the provision of the Act of Parliament with regard to the weight to be carried by the trucks was not observed, and whether the occurrence was in any way consequent upon it. It seemed to him a terribly unsafe practice for men to have to go between the trucks when in motion for the purpose of applying the brakes to them.

Whatever the result of their verdict, it seemed highly important that the jury, having regard to the evidence of the engine driver as to the danger and difficulty – the almost absolute impossibility – of controlling traction engines on steep hills and smooth roads (always found in towns), should consider whether it was not their duty to make some urgent representation to the Home Secretary or the County Council as to further regulations. The Act of Parliament applied to the whole of England. But what was safe for the Midlands, where the roads were wide and level, might not be safe for that part of South Devon. The Act gave power to County Councils to make certain regulation but in the regulations of the Council of Devon there was nothing affecting the question of hills. If the jury found that the child’s death was produced by this occurrence, and that the latter was brought about by neglect or a want of proper care and precautions working the locomotive, the persons responsible would also be responsible for the child’s death, and would have to take their trial.

The Verdict

The Jury returned at a quarter to eleven with a verdict of manslaughter against Fenton, the owner, and Maffey, the driver, twelve having agreed with one dissentient. They added the rider that the County Council’s attention be called to the fact that the regulations for traction engines travelling on hilly roads such as South Devon are inadequate and the said traction engines are dangerous to human life and property, and liable at any moment to get beyond control. To prevent further disasters such as took place at Teignmouth on Friday last the jury recommend the said County Council to apply to Parliament to enforce better regulations for locomotives travelling on hilly roads.

Mr Hutchings said the father of the deceased child (Sergt-Instructor Waite), would like to publicly thank Wm. Woodley, who extricated the child by knocking away the bricks after it had been jammed between the end of the engine so many hours. The Coroner concurred and thought it very humane on the part of Woodley.

It being after hours Sergt. Richards proceeded to clear the room, whereupon the Coroner reminded him that whilst on licensed premises that room was a coroner’s court of inquiry and the public were privileged to stay, provided no drink was drawn. This announcement was received with applause.

The Commitment

The Coroner committed Mr Fenton and Mr Maffey immediately from that Court to the Assizes (this week) for trial on the charge of manslaughter, granting bail, Mr Fenton in his own recognizance £100, and two sureties of £100 each; Maffey’s recognizance with £50 and two sureties of £50 each. In both cases the sureties were Mr Chas. Ingram, Torquay, and Mr H. Stanbury, Teignmouth.

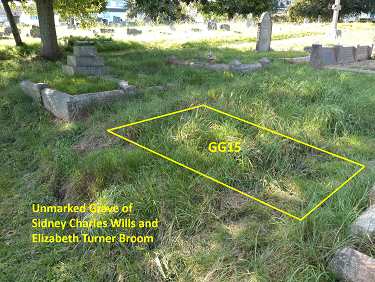

The Funeral

The funeral of the little one took place on Tuesday amidst tokens of much sympathy. The coffin was of elm, covered with violet cloth with white metal mountings, and a plate bearing the name “Frances Maude Waite. Died June 12, aged 7 years and six months.” Wreaths and floral tributes were sent in abundance from all parts of Devon. Those who followed as chief mourners were the father and his four daughters. The service at the cemetery was conducted by the Rev J. Metcalfe, and Mr W. Tapper carried out the arrangement.